Diabetes is the leading driver of kidney disease, a potentially fatal condition affecting 37 million Americans, many of whom are unaware that their kidneys are ailing. No cure exists, and current treatments for end-stage disease primarily are limited to dialysis and kidney transplant.

In pursuit of improved drug therapies to protect the kidneys of patients with diabetes, a mouse study led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that combining SGLT2 inhibitors — a newer class of diabetes medications that lowers blood sugar — with older diabetes drugs may help to slow the progression of diabetic kidney disease.

Commonly prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors include dapagliflozin (Farxiga), empagliflozin (Jardiance) and canagliflozin (Invokana). The latter is made by Janssen Pharmaceuticals, whose scientists collaborated on this study.

“SGLT2 inhibitors have had remarkably positive effects on kidney disease in diabetes, the best effects that we have seen in decades, yet scientists have not understood specifically how and why these drugs work so well,” said senior author Benjamin D. Humphreys, MD, PhD, director of the Division of Nephrology at Washington University. “By studying mice, we found that these drugs may work even better to protect the kidneys when combined with other diabetes drugs, and with this approach we should be able to achieve better outcomes in patients because the drugs act in a synergistic way on the kidneys, at least at the cellular level.”

The findings are published June 15 in Cell Metabolism.

Diabetic kidney disease occurs in about 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes, leading to kidney failure, cardiovascular disease and premature death. Black people, Native Americans and Hispanics develop diabetes, kidney disease and kidney failure at higher rates than Caucasians.

Diabetes damages the kidneys by preventing the organs from effectively filtering waste and excess fluids from the body. Because symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, sleep disturbances and swollen limbs are common and nonspecific to kidney disease, most people don’t realize they have it until irreparable organ damage occurs.

SGLT2 inhibitors — formally known as sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors — prompt the kidneys to eliminate excess sugar from the blood, and such sugar is removed from the body through urine. “What’s more, this class of drugs is also highly protective for heart disease,” said Humphreys, who also is the Joseph Friedman Professor of Renal Diseases in Medicine.

Most patients with type 2 diabetes are prescribed only a single drug, but the study’s results suggest that combination therapies may be more effective because the different drug classes target different cell types in the kidney.

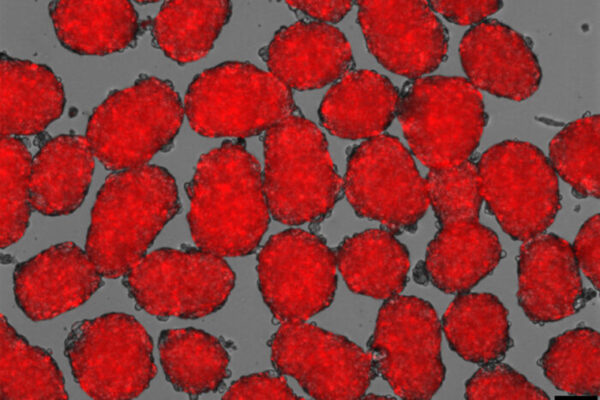

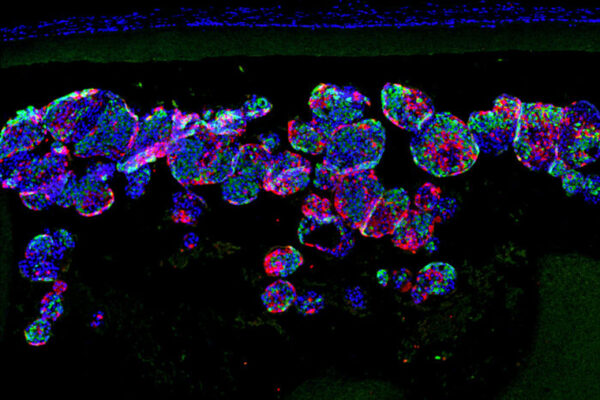

Studying mice that had developed diabetic kidney disease, the researchers analyzed how mouse kidneys respond to five diabetes treatment regimens prescribed to patients. The team examined responses using single-cell RNA sequencing, which allowed them to identify changes in the kidneys at the cellular and molecular level to the different treatments. Understanding such interworkings can help researchers target specific cells to improve drug therapies.

They studied the effects of individual classes of drugs and combinations of drugs, focusing on three classes of drugs: SGLT2 inhibitors; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), such as Lisinopril; and Thiazolidinediones (TZD, also known as insulin sensitizers). Rosiglitazone is a common TZD.

“We designed our study to try to understand how combination therapies affect the kidney differently than single therapies,” said the study’s first author, Haojia Wu, PhD, an assistant professor in the Division of Nephrology. “We found that each of the different classes of drugs targeted different cell types, providing a cellular rationale for combination therapies to better slow progression in diabetic kidney disease.”

The study found that the combination of SGLT2 inhibitors with Lisinopril had better protective effects on the kidney than any of the single therapies alone.

The researchers also noted that SGLT2 inhibitors seemed to trick the kidney into activating a starvation response, similar to how the body slows down its metabolism when fasting for prolonged periods. “This may reduce overall energy consumption in the kidney, allowing it to work more efficiently and placing less of a burden on it long term, possibly explaining why this class of drugs is so effective,” Humphreys said.

“We are in a very exciting time for treatments of diabetic kidney disease,” he added. “Our study adds to growing evidence that combination therapies offer strong benefits to patients. We think such approaches should be adopted in routine clinical practice.”

Humphreys said that future observational studies in people taking combination therapies should provide further evidence.

Wu H, Gonzalez Villalobos R, Yao X, Reilly D, Chen T, Rankin M, Myshkin E, Breyer MD, Humphreys BD. Mapping the Single Cell Transcriptomic Response of Murine Diabetic Kidney Disease in Therapies. Cell Metabolism. June 15, 2022.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers DK20579 and DK103740; the Washington University Diabetes Research Center; and a sponsored research agreement from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Gonzalez Villalobos, Yao, Reilly, Chen, Rankin, Myshkin, and Breyer are employees of Janssen Research & Development. Breyer holds Johnson & Johnson stock. Humphreys is a consultant for Janssen Research & Development, Pfizer and Chinook Therapeutics. Humphreys holds equity in Chinook Therapeutics.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 1,700 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, and currently is No. 4 in research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.