Misi-ziibi means “great river” in the Anishinaabe language. For the Native peoples of upper Minnesota, misi-ziibi referred to the long, 1,300-mile stretch flowing south of the Crow Wing River, past present-day St. Louis and into the Gulf of Mexico.

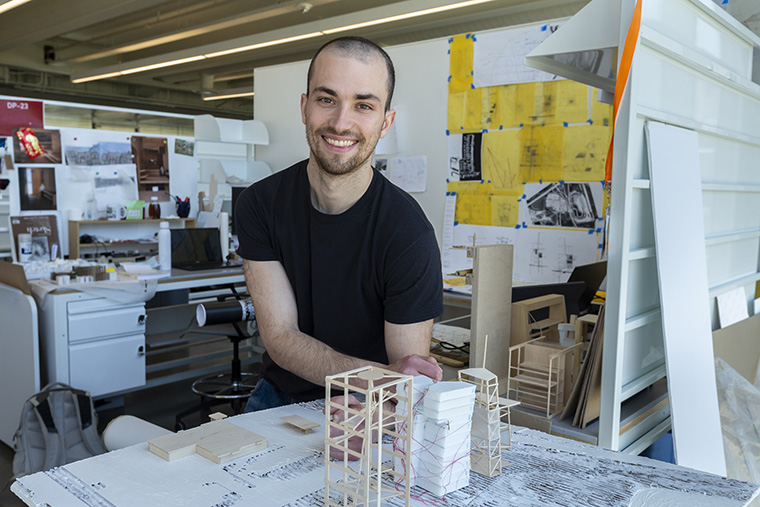

But the name was not the only thing taken from the Anishinaabe, argues Nathan Stanfield, who is set to earn his master’s degree in architecture this spring from the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis.

In “Decolonizing Water: Native Histories and Futures in the Mississippi River Basin,” a research fellowship funded by WashU’s Divided City initiative, Stanfield investigated how levees, dams, pipelines and other systems of control have perpetuated centuries of environmental injustice.

“Water connects us, both literally and metaphorically,” Stanfield explained. But where traditional Native practices largely harmonized with the Mississippi’s natural topography, since the 1930s, large-scale public works have transformed the river into a highly constructed, and actively managed, system — a profound change with consequences both unintended and unacknowledged.

“I wanted to understand the impact of these infrastructural interventions on Native land and water,” Stanfield said. “Who was affected? Who was displaced? And how can we support Indigenous sovereignty and environmental stewardship?”

A medium for conversation

Raised outside Boston, in Dorchester, Mass., Stanfield earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture, along with a minor in philosophy, from the Sam Fox School in 2018. “The minor was almost accidental,” Stanfield said with a laugh. “I’d taken so many philosophy courses, I realized I was just a few credits away.”

After a summer internship with the Kansas City architecture firm Populous, Stanfield returned to Boston as a project manager with Maryann Thompson Architects. There, he served as lead designer for the net-zero renovation of a private modernist residence, among other projects.

But Stanfield remained in touch with his old professors, especially Derek Hoeferlin, chair of landscape architecture and urban design. In the fall of 2020, as COVID-19 wreaked havoc in the architecture and construction industries, Stanfield returned to WashU as a Sam Fox Ambassadors Fellow.

“As a kid, I liked drawing, I like building things, I liked math,” Stanfield said. “Architecture seemed to cover those bases.

“But architecture also can be a medium for conversation and public awareness,” Stanfield added. “What changes need to be made, and how can design participate?”

Stories of erasure

In many ways, “Decolonizing Water” grew out of Stanfield’s work with Hoeferlin for “Exhibit Columbus,” a sprawling invitational that takes place annually in the small but architecturally prestigious city of Columbus, Ind.

Hoeferlin, an authority on water-based design, had assembled a team to develop “Tracing Our Mississippi,” which would investigate “the relentless infrastructures controlling the Mississippi’s landscapes, communities and resources.” The installation debuted in August 2021 and included large-scale models (designed, milled and assembled in the Sam Fox School’s Weil Hall) as well as oral histories and public outreach events.

“The collaborative project was not exactly the model,” Stanfield explained to Archinect, but rather the “research-intensive process of making and learning through making.” At the same time, the team aspired not just to communicate the reality of how the river functions today, but also “the overlooked story of the erasure and manipulation of the watershed’s Native communities and ecology.”

Recently, Stanfield presented his degree project, which explores material extraction and waste economies in the American Bottom flood plains east of St. Louis. Titled “Bricolage,” the proposal examines the potential for recycling plastic bottles into wall systems. It also highlights the fraught juxtaposition of Cahokia Mounds, a UNESCO World Heritage Site marking one of the largest pre-Columbian cities in North America, and Milam Landfill, a 20-story trash pile located about 3 miles away.

“People often mistake the landfill for (Cahokia’s) Monks Mound,” Stanfield said with a shake of the head. Problematic symbolism aside, “having a landfill in a floodplain is a major issue. If water ever tops the levees,” such as during a flood or seismic event, “the ramifications will affect the entire region.”

Music of the sphere

In recent months, Stanfield also has been exploring the relationship between architecture and sensory experience, particularly music. On May 14, he will debut an original composition at WashU’s Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum as part of the multimedia showcase “Kemper Live: Here and Now.”

Stanfield’s piece, titled “Pendulum,” was created in response to both “A Sound, A Signal, The Circus,” a new multi-sensory environment by artist and filmmaker Nicole Miller, and Olafur Eliasson’s “Your Imploded View” (2001), a 661-pound aluminum sphere suspended from the ceiling in the museum’s Saligman Family Atrium.

As an architect, “you can learn from things that are not architecture,” said Stanfield, who conceived “Pendulum” as a “sonic dialogue” between Library of Congress recordings and ultrasound mapping of the sphere’s speed and path when set in motion.

“Architecture is actually very similar to music,” Stanfield added with a smile. “It’s a process of iterating and critiquing and working through layers of information.

“You experiment, you try something, and if it doesn’t work, you try something else.”