Sculptor Bo Schmit can carve and cast, mold and weld, sew and sand.

He also can shop.

Schmit frequently scavenges thrift stores and metal suppliers for domestic detritus, the building blocks of his intimate objects and large-scale installations. The results are sometimes whimsical, sometimes disturbing and, somehow, always familiar.

“I ask my materials to do a lot of heavy lifting,” Schmit said. “Found objects naturally convey a specific sense of history. You can tell a bed sheet from a tablecloth from a curtain. And you can imagine how a human body would interact with those pieces.”

Schmit is set to graduate with a degree in studio art from the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. One of three Sam Fox students nominated for the International Sculpture Center’s Outstanding Student Achievement Award, Schmit explores themes of gender, sexuality and the human body through the use of gendered materials such as wood and fabric and gendered techniques like carving and sewing. For Schmit, message, material and method are inextricably tangled.

“What I’ve learned about myself is that my own tactile interest in different materials is tied to my interest in sexual and gendered experiences and the anxiety and playfulness they can produce,” Schmit said.

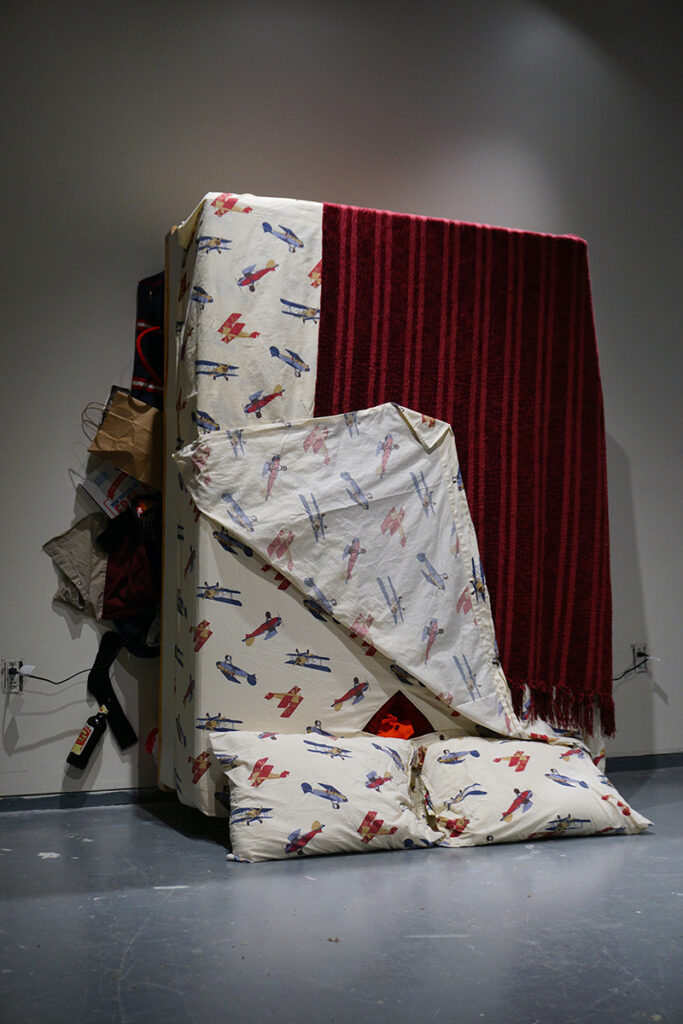

An early example is his installation, “The Phenomenon of Mourning Things Which Were Never Lost,” a reference to Schmit’s childhood as a transmasculine person. The installation consists of a mattress constructed of insulation foam and propped upright. The bed, covered with airplane sheets, clearly belongs to a boy. But a closer look reveals a tiny, triangular cut out at the base of the bed.

“You get down on all fours and see this red-lit shrine to girlhood – a hairbrush, Girl Scout cookies, a bralette, sanitary pad,” Schmit said. “The objects of girlhood are pulled from my memories and represent my real experience set inside this realistically rendered fantasy experience of the boyhood I feel like I missed out on.”

Schmit uses materials to similar effect in “Boyhood Crush.” A dainty rose florette, snipped off a thrift-store slip, connects two pennants of fabric – a top layer that Schmit soaked in polyurethane and rubbed with ash and then meticulously stitched to panels of ivory lace. The piece is both a commentary on adolescent sexual awakening and a showcase of Schmit’s mastery of materials and handicraft.

“I had been wanting to explore that space between the innocence and purity girls are supposed to have growing up and the more aggressive type of sexuality that is expected from men,” Schmit said. “The fabrics are like skin — the lace is supple and soft; the top layer is callous and rough. And then there is that little flower in the center that is so loaded and powerful.”

Arts & Sciences and the artist

Schmit grew up in Salem, a small rural community in central Missouri. His school district’s art program was not especially well funded but it did boast committed teachers who encouraged Schmit to pursue art as a career. Still, Schmit had doubts.

“There are a lot of talented craftspeople in my town, so there is a regard for art that’s functional or decorative,” Schmit said. “But that’s very different from the work I create. The thinking is, ‘Go ahead and make your art, but you’re not going to be an artist. No one survives making art.’”

Schmit considered art institutes in Kansas City and Chicago but chose Washington University because he wanted the freedom to explore topics outside of his major.

“My WashU education has been so broad,” said Schmit, who minored in American culture studies in Arts & Sciences. “I’ve had the opportunity to learn about different ideas, from the social policing of sexual and gender identities to material culture to visual culture. All of these ArtSci classes have been integral to me as a person and have had a big influence on my art practice.”

After graduation, Schmit will work as a studio assistant for artist Noah Kirby, who teaches blacksmithing and metal fabrication at the Sam Fox School and operates Six Miles Sculpture Works in Granite City, Ill. In exchange for his own studio space, Schmit will help Kirby weld and install large-scale public art installations. Schmit has worked with metal before, casting bronze bells as an intern at Sunderlin Bellfoundry in Virginia, the only traditional bell foundry in the United States.

“I’m really drawn to this idea of handicrafts, whether it’s quilting or casting metal,” Schmit said. “I love the idea of investing yourself into your materials so that you can see yourself in something else and let your own experiences, memories and thoughts flow into the work.”

Ultimately, Schmit would like to show in galleries, collaborate with other artists and, yes, survive as an artist.

“We’ll see if I can show the folks back home you can be an artist,” Schmit said.