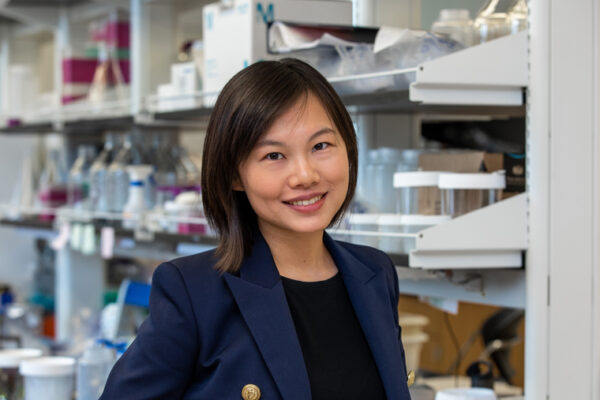

You may not know her name, but the superintendent of your child’s school district certainly does.

For decades, Victoria May, executive director of the Institute for School Partnership at Washington University in St. Louis, has worked with local educators to create high-quality, equitable education for all students. She helped develop the hands-on mySci curriculum, which is taught in nearly every school district in the region as well as many private and charter schools. She and her team also have launched initiatives like STEMpact and Math314, which improve learning in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM); developed programs such as the Transformational Leadership Initiative, which help teachers grow as leaders in their classrooms and their schools; and, most recently, gathered a cohort of St. Louis Public Schools principals to design a new vision for their schools.

“If you want a great city, you have to have great schools, and the way you do that is one teacher, one educator and one school at a time,” May said. “It takes time and it takes trust. You have to build relationships that are authentic and sustainable and to show up in a spirit of collaboration.”

May is one of seven members of the Washington University community who were honored April 19 at the Gerry and Bob Virgil Ethic of Service Awards, sponsored by the Gephardt Institute for Civic and Community Engagement. Now in their 19th year, the awards celebrate leaders who are devoted to improving the St. Louis region.

Provost Beverly Wendland nominated May, praising her for the breadth and depth of her impact.

“Vicki’s driving goal is to expose all students to high-quality STEM curriculum early so that they can build confidence in their science, technology and math skills as well as build an awareness of the opportunities available to them in STEM-related careers,” Wendland wrote in her nomination. “Vicki has also worked closely with schools to implement new approaches to leadership. Vicki’s passion and drive coupled with her commitment to the belief in distributive leadership acts to create equitable learning spaces. Such spaces can empower students to think critically, problem-solve creatively and engage with the world’s challenges and possibilities.”

Here, May shares how ISP approaches STEM education, why teachers need our support and what ISP initiatives promise for the future.

What does equity in education mean in the context of STEM education?

All students deserve to experience high-quality education and to be loved and cared for. In the context of STEM education, that means building a strong foundation in math and science at a young age and helping students see themselves as scientists. It’s like our founder Sally Elgin said from the very beginning — You would never teach art by only reading art history books. The same goes for STEM. We put tools in the hands of students so they can actually do the science and give them the academic vocabulary to engage in conversations about what they are learning. This matters because there are so many opportunities in STEM careers, jobs that can lift up families, the region and the world.

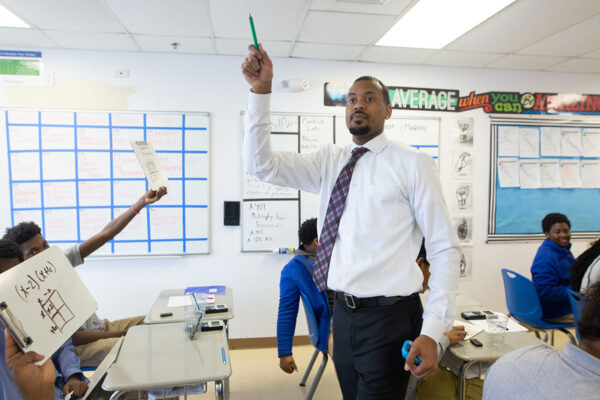

From professional development workshops to the St. Louis Teacher Residency, ISP is committed to helping educators grow and lead. Why are teachers at the center of your work?

I don’t think people realize the number of decisions a teacher makes every hour and the stamina it takes to do this job. So one part of our work is to provide that listening ear. We also are out there reading the latest research and going to conferences and then translating that information into strategies that teachers can put into practice immediately. And because we work with thousands of teachers, we also play an important role as convener, bringing teachers together so they can learn from one another.

ISP also is proud of its partnership with the St. Louis Teacher Residency, which is tackling the challenge of teacher retention and teacher quality in school. These residents, many of whom are educators of color, are in the classroom on Day 1. They are provided subject matter expertise, classroom management skills and the ongoing support they need to grow and develop as teachers.

And that is so important. Teachers don’t get into this work for the money; it’s a calling. But they will leave if their voices aren’t heard, if they aren’t supported by their principal, if they are not engaged in meaningful work.

ISP is engaged in dozens of partnerships across the region. What are some efforts that excite you?

I’m excited about the work that’s happening at Consortium Partnership Network schools, Ashland and Meramec elementary schools in St. Louis Public Schools, where you are really seeing deeper learning and deeper leading coming together. Those schools are asking really interesting questions: ‘How do we bring in the teacher voice? How do we build leadership teams that can maintain a school’s culture? What does-high quality instructions look like?’

The SLPS principal program also is promising. It’s giving principals some space to reenvision their schools. It’s about going beyond, ‘I need paper for teachers,’ to thinking about meaningful ways they make their schools better.

And, for the first time, we are working with pre-K students in a partnership with the Julia Goldstein Early Childhood Education Center in University City. A lot of early-education programs focus on counting, but research tells us that the ability to recognize patterns is really important and will lead to improved literacy in math scores. So we are working with the center’s teachers, who are already using patterns in really fun ways such as singing and clapping, to develop lessons that will lead to deeper learning. Our goal is take those lessons and bring them to other preschools so that the entire region can benefit.

The Institute for School Partnership is one way Washington University faculty, staff and students are working to improve K-12 education in St. Louis. To learn more, visit The Pipeline.