Can you ever escape your past?

Tennessee Williams spent a lifetime trying. His years in New York, New Orleans and Key West are the stuff of literary legend. But it was St. Louis where Williams lived the longest, St. Louis that shaped him as both an artist and a person, and St. Louis he spent decades rebelling against.

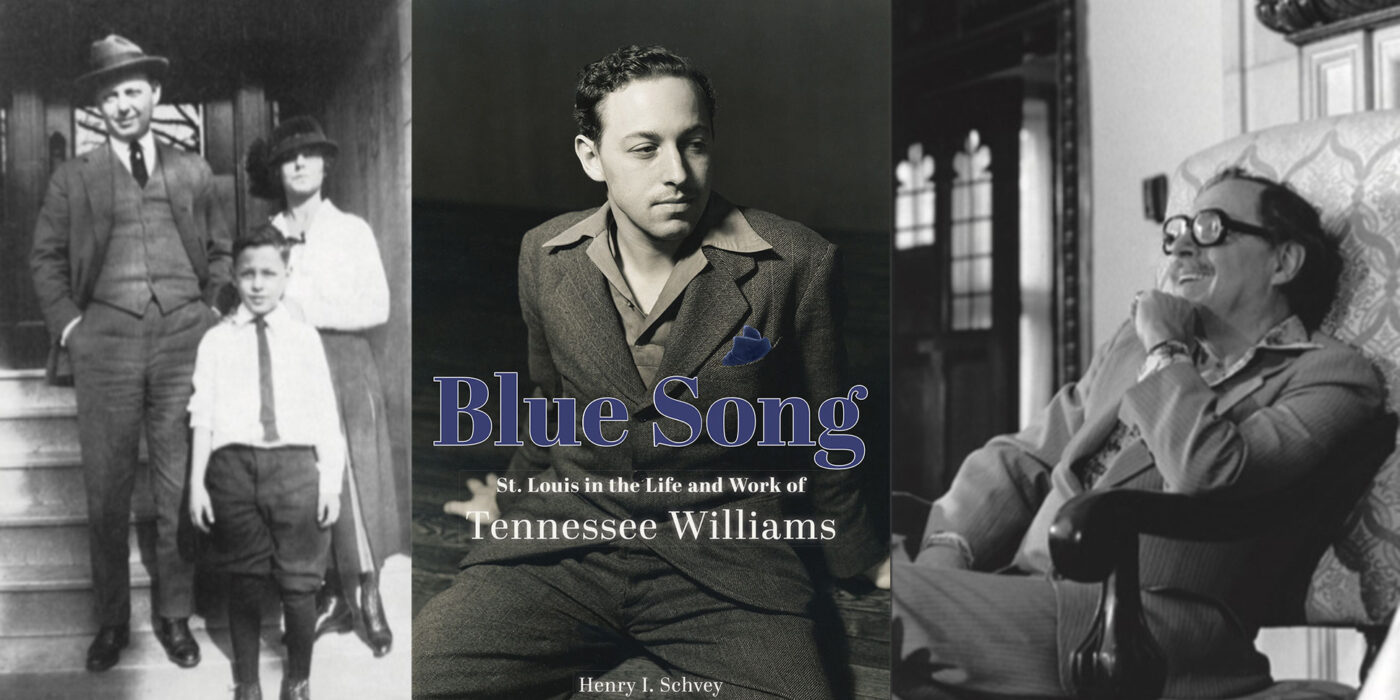

So argues Henry I. Schvey in “Blue Song: St. Louis in the Life and Work of Tennessee Williams” (2021). In this Q&A, Schvey, professor of drama and comparative literature in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, discusses Williams’ early years, his time as WashU student, and the truce the playwright eventually struck with the city of his youth.

“Blue Song” begins with the first words that Williams heard upon arriving in St. Louis, at the age of 7. What were they, and what do they foreshadow?

“Never let me catch you stealing again!”

In July 1918, young Tom Williams and his mother Edwina arrived at Union Station from Clarksville, Miss. The words were spoken to him by his father, Cornelius (C.C.) Williams, as Tom plucked a grape from a passing fruit vendor, and were accompanied by a sharp slap on the wrist.

The words were so memorable they were recalled in Williams’ “Memoirs,” more than half a century later. The words created a permanent association between the city of St. Louis and notions of repression and constraint, which the mature writer rebelled against. This rebellion is at the core of nearly all of Williams’ work.

You point out that, for all his association with the American South, Williams lived in St. Louis longer than he lived anywhere else. How did the city shape him?

In contradistinction to most scholarly interpretation, I argue that St. Louis was absolutely indispensable for the writer as something to rebel against. It provided him with his most fruitful and compelling subjects — the world of the senses, in opposition to the middle-class world he was surrounded by growing up. Whereas the New Orleans of the French Quarter, Provincetown and later Key West all contributed to his sexual and emotional liberation, it was St. Louis where he found his vocation as a writer.

But St. Louis was not merely important as a negative example — it provided positive influences as well. In the urban Midwest he despised, the young Williams was given a progressive, first-class, public-school education at Ben Blewett Junior High School and University City High School. He would never have obtained such educational opportunities in the rural South he romanticized. At Washington University, Williams found kindred spirits, such as Clark Mills and William Jay Smith, who shared his passion for literature and writing. And in the community theater group called the Mummers, he found a mentor, Willard Holland, and a company of actors that provided him with a living laboratory to test his burgeoning talent.

Ultimately, St. Louis provided this most autobiographical of writers with his true subject matter — his own family. His bullying father, his smothering mother, and particularly his sister Rose, the person he was closest to and whose mental illness and eventual prefrontal lobotomy formed the imaginative center of so much of his work.

Critics sometimes dismiss the plays Williams wrote in St. Louis as “apprentice works.” You resist that label. Why?

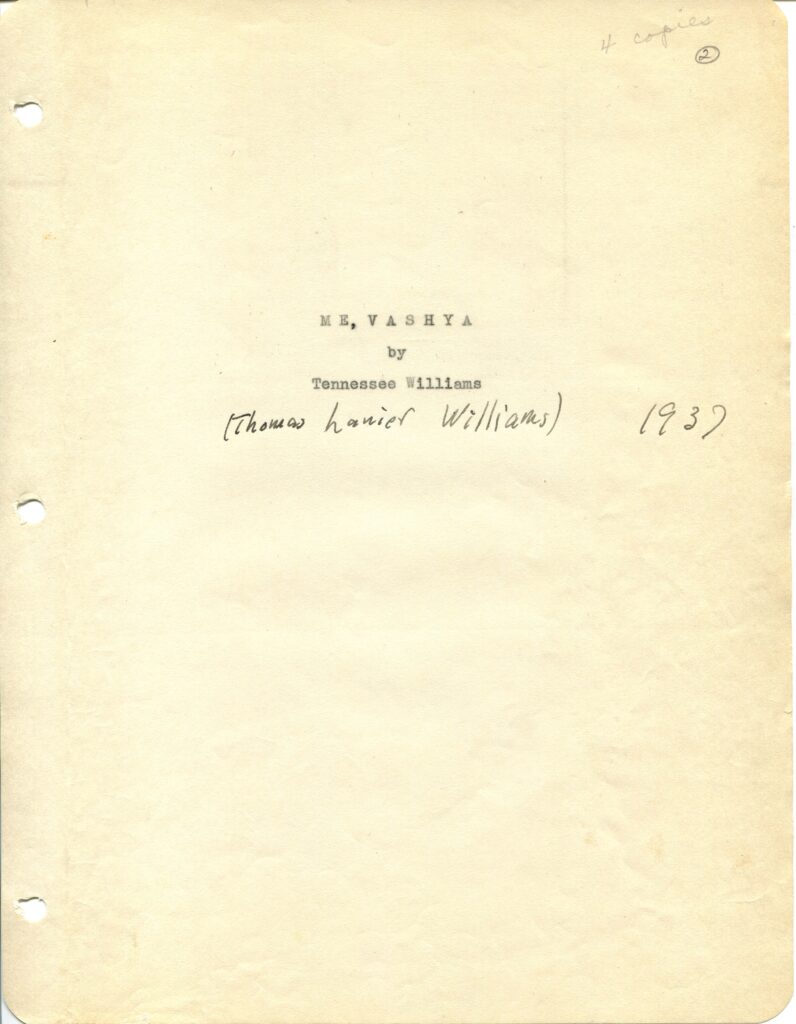

These plays don’t conform with pre-existing scholarly narratives about the artist coming of age in New Orleans before emerging on Broadway with “Menagerie” (1944) and “A Streetcar Named Desire”(1947). In presenting Williams as a “Southern” writer, scholars took their lead from Williams himself, who did as much as he could to create this persona as “Tennessee” and discourage the association with the town he called “Saint Pollution.”

The early plays, however, are tremendously revealing. They show a writer deeply concerned and influenced by the Great Depression and the social and political conditions of the 1930s, conditions that adhere with the artistic doctrine of The Mummers, who commissioned them. Both “Spring Storm” (1937) and “Not About Nightingales” (1938) — which were lost for decades until their rediscovery in the late 1990s — reveal astonishing artistry in the creation of scores of characters and in the playwright’s remarkable handling of dialogue. “Spring Storm” also reminds us that Williams’ true subject really never changed. He was always writing about himself and his sister in different guises.

Meanwhile, “Candles to the Sun” (1936) takes place in an Alabama mining community Williams had never visited, yet the St. Louis Post-Dispatch lauded the young writer for his keen ear for local speech he had never actually heard. The characterization of “juvenilia” simply doesn’t hold.

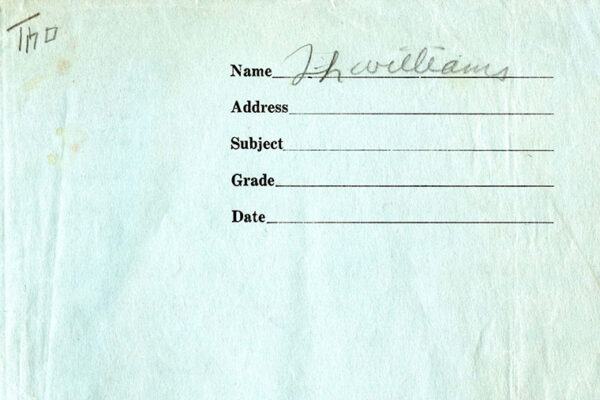

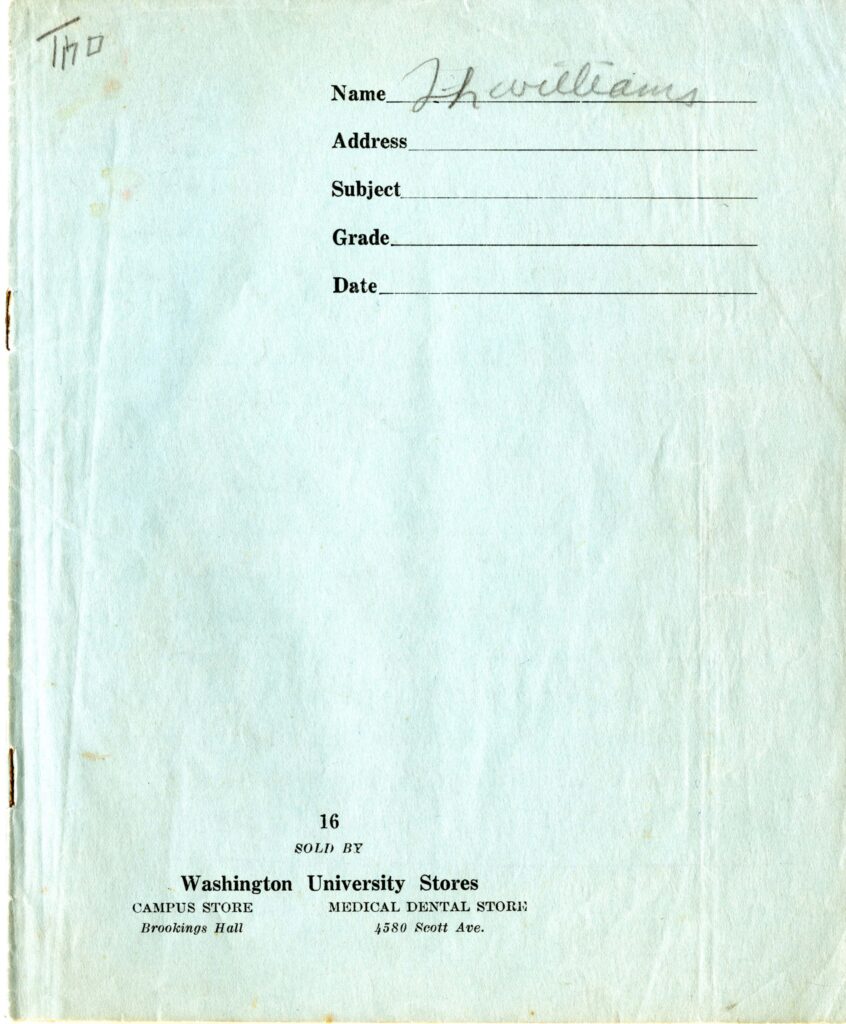

“Blue Song” takes its name from a poem that you discovered in one of Williams’ old test booklets. But blue also seems like a running preoccupation for Williams, from the “Blue Roses” and “Blue Mountain” of “Glass Menagerie” to the “blue devils,” as Williams described his melancholia. Can you say a few words about Williams’ use of blue, as both a color and a mood?

I think your description is absolutely correct. The color blue is associated with sadness and depression in Williams, and the reference to “blue devils” is a code word for depression sprinkled throughout his journals and letters, as well as the plays. It is beautifully and perhaps most succinctly described in his last great Broadway success, “Night of the Iguana”(1961), where the painter Hannah Jelkes describes the “subterranean travels spooked and bedeviled people are forced to take through the unlighted sides of their natures” to cope with their blue devils

You write that “A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur” (1979), the first play Williams set in St. Louis since “Menagerie,” represented “a truce between Williams and his St. Louis past.” Why do you think Williams finally called a ceasefire?

Williams kept returning to St. Louis throughout his life, since his mother, Edwina, resided here until her death in 1980. He also was forced to return to St. Louis for three months in the fall of 1969, when he was interned by his brother Dakin at the Renard Division of Barnes Hospital for drug and alcohol addiction. This was a time of violent antagonism toward the city. It is hard to imagine what he must have felt — a world-famous writer attempting to conceal his identity by using his old name, “Tom”; winding up hospitalized at the very place where Rose’s mental illness was first diagnosed.

However, by the late 1970s he seems to have lost some of that hostility. In 1977 he did a reading at [WashU’s] Graham Chapel, and listening to the recording, one senses that he’s relaxed and at ease. He never mentions that, in the spring of 1937, he had been utterly devastated and humiliated after receiving an “honorable mention” in Professor William G.B. Carson’s English 16 undergraduate playwriting contest! At the time, he wrote of Professor Carson’s decision not to award him a prize: “why should I expect sympathy from anyone — especially a Washington University Professor — the stronghold of the Reactionaries!”

Yet the portrayal of St. Louis in “Creve Coeur” (set in the 1930s of his youth) is affectionate rather than savage. He seems to smile at the city’s provinciality instead of resenting it. The choice to end this lyrical little play with a picnic at Creve Coeur Lake seems to epitomize a gentle acceptance of the place he formerly needed — in asserting his youthful freedom and independence — to despise.

Schvey will discuss “Blue Song” in a free Zoom talk for University Libraries at 4:30 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 20. In addition, Schvey will speak at 7 p.m. Nov. 14 as part of the St. Louis Jewish Book Festival, in a conversation moderated by St. Louis Public Radio’s Sarah Fenske. For tickets or more information, visit jccstl.com.