Respiratory syncytial virus, more commonly known as RSV, is a highly contagious respiratory virus that can be very serious and even fatal for young children and the elderly. In summer of 2021, health-care providers saw an unseasonable spike in the virus, which typically causes illness from October through March. While the virus has been recognized since the 1950s, there is no vaccine available.

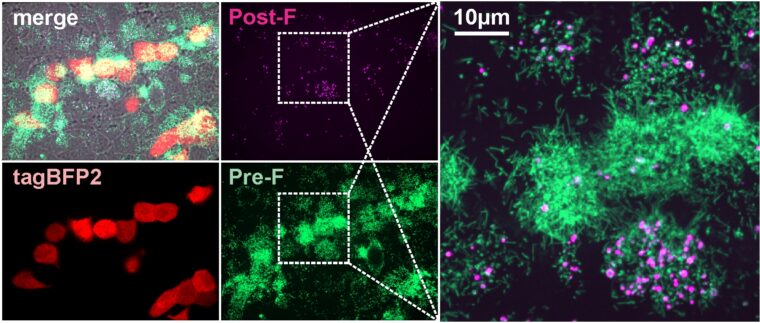

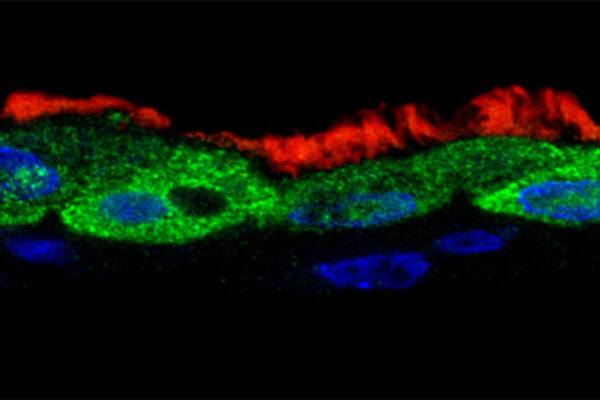

Michael D. Vahey, a biomedical engineer at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, along with Jessica Kuppan and Margaret Mitrovich, both doctoral students in his lab and co-first authors of the paper, has developed a fluorescent system allowing him and his lab members to monitor the interactions between the virus particles and the proteins in the immune system that help to defend against infections, known as complement proteins. Through this system, they found that the viruses produced during RSV infection change shape — converting from long, rod-shaped particles to more rounded ones — and this makes a difference in whether the complement proteins are activated or not. Results of the work are published online in the journal eLife.

For RSV viruses to infect a cell, the membranes surrounding each of them have to fuse together through the action of the RSV F protein. Antibodies that bind to the F protein can prevent the virus from infecting cells. But the F protein is a well-known shape shifter, making it notoriously unstable, said Vahey, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, who studies infectious diseases.

“Ideally, we would like the immune system to target the form of F that can cause infection, but this doesn’t always happen,” Vahey said. “We found that when RSV changes shape from rods to spheres, the F protein tends to change shape, too. What we end up with is a situation where the virus particles that activate the complement system frequently have the wrong form of F on their surface. This may instruct the immune system to go after the wrong target.”

Vahey said the findings show that the biophysical properties of a virus, including its size and shape, matter in terms of how it is recognized by the immune system and may be important to consider when developing potential treatments or vaccines.

Funding for this work was provided by Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Awards at the Scientific Interfaces grant and Washington University in St. Louis.

Kuppan JP, Mitrovich MD, Vahey MD. A morphological transformation in respiratory syncytial virus leads to enhanced complement deposition. eLife, published online Sept. 29, 2021. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.70575

The McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis promotes independent inquiry and education with an emphasis on scientific excellence, innovation and collaboration without boundaries. McKelvey Engineering has top-ranked research and graduate programs across departments, particularly in biomedical engineering, environmental engineering and computing, and has one of the most selective undergraduate programs in the country. With 140 full-time faculty, 1,387 undergraduate students, 1,448 graduate students and 21,000 living alumni, we are working to solve some of society’s greatest challenges; to prepare students to become leaders and innovate throughout their careers; and to be a catalyst of economic development for the St. Louis region and beyond.