A van gleams darkly in the seedy neon of 1970s Times Square. Taxis queue for gas amidst a global oil crisis. In Los Angeles, sprawling development commands acres of flat-lot parking — a feedback loop of urban emptiness.

In “The Autonomous Future of Mobility,” Constance Vale, assistant professor of architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, explores how motorized travel shapes American cities, energy consumption and popular notions of freedom and independence.

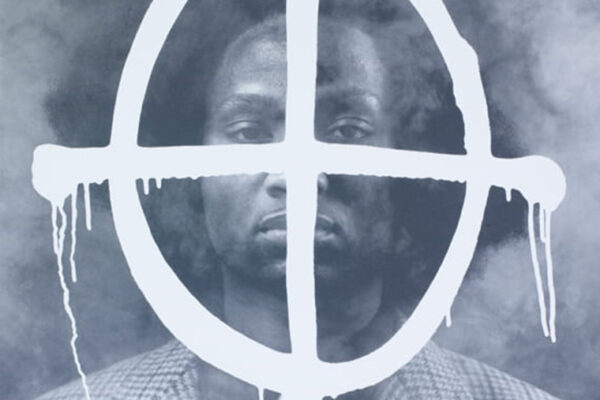

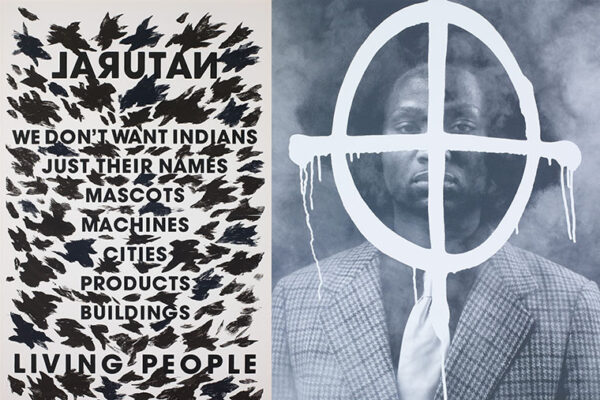

The exhibition, which is on view in the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum’s Teaching Gallery, and also virtually through the museum website, features 18 works in a variety of media, from photography and painting to prints, artist books and video.

“Cars are objects of desire, tied to personal identity and presented as extensions of the individual,” Vale observed. “They have shaped our cities in significant and positive ways,” yet, “they are tied to a set of catastrophes, including vehicle crash fatalities, environmental and atmospheric damage, military conflicts, insufficient infrastructure, and economic injustice and segregation in cities via the expansion of highways and use of eminent domain.”

Now, with artificial intelligence and self-driving vehicles on the not-so-distant horizon, “it is crucial to assess how architects, urban designers and engineers can approach the design of cities in ways that address new technological imperatives and ongoing sociopolitical and environmental problems tied to the legacy of the car,” Vale added.

Related: Read the full curator’s statement here.

Culture, signs, space, speed, energy and autonomy

Entering the Teaching Gallery, viewers are greeted by two distinct visions of motorized autonomy. Robert Breer’s kinetic sculpture “Float” (1972), designed to glide slowly about the gallery floor, is an early example of a self-navigating object. Trevor Paglen’s photograph “Untitled (Reaper Drone)” (2010) depicts the paradigmatic 21st-century weapon as a distant speck barely visible on the morning sky.

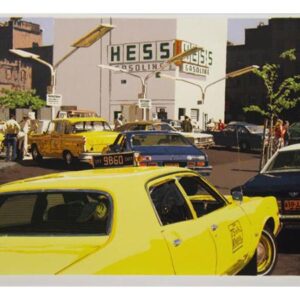

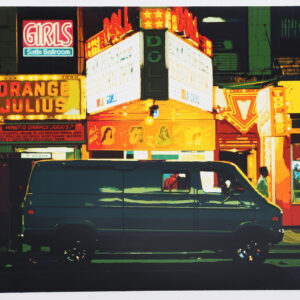

On the adjacent wall, Andy Warhol’s “Truck” (1985) reflects the artist’s preoccupations with vehicles, consumer goods and commercial branding. Noel Mahaffey’s moodily chiaroscuro “Night—Times Square” (1979) links car culture to the power dynamics of class, segregation and urban decline. Larry Stark’s “May 16th, 1970” (1970) depicts a blackened smokestack towering over treetops and the brightly colored logo of a bygone oil company — an image at once requiem and warning.

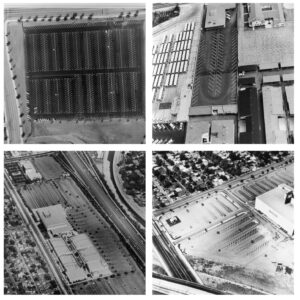

Ed Ruscha’s “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” (1963) captures the paper-thin commercial architecture on which vehicular infrastructure is largely built. In deadpan anticipation of Google Street View, Ruscha’s “Every Building on the Sunset Strip” (1966) documents the full 1.5-mile length of the nation’s most celebrated auto promenade, while “Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles” (1967) depicts the vacancies, simultaneously eerie and ironic, of spaces intended to facilitate travel.

‘The mobility of our time’

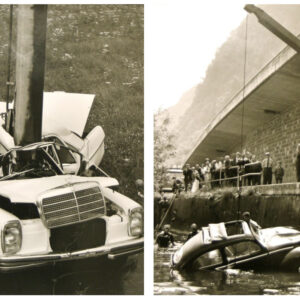

Other works, by John Baeder and Irma Bloom, explore the car’s place in American culture, while Garry Winogrand examines its effect on pedestrian spaces. John Chamberlain, Doug Aitken, Arnold Odermatt and Robert Stanley explore the allure and vulnerabilities of unchecked speed. Ron Kleemann highlights the automobile’s economic impact, in all its power and fragility.

“The mobility of our time is unique in its independence from human intervention and sight, but is still entangled with social, political and economic realities,” Vale said. At the same time, “it is possible to imagine a very different vehicular landscape, one that aims to reduce or eliminate the environmental damage and political problems that cars have wrought through re-envisioning the role of the car in our lives and designing cities with embedded intelligence that takes advantage of energy-conserving transit.”

Vale concluded: “With architecture and urban planning that prioritize public over commercial and private interests, and the thoughtful incorporation of autonomous mobility that accounts for infrastructural and spatial considerations, our world might be one in which the individual mobility and freedom that the car provides no longer come at the cost of social and collective liberty.”

The Teaching Gallery

The Teaching Gallery is an exhibition space within the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis. It is dedicated to exhibiting works from the museum’s collection with direct connections to university courses. Teaching Gallery exhibitions are intended to serve as parallel classrooms and can be used to supplement courses through object-based inquiry, research and learning.

“The Autonomous Future of Mobility” remains on view through March 12, 2021. Due to COVID-19, the museum is closed to the public but is available to WashU students, faculty and staff. To see the virtual exhibition click here.

For more information, call 314-935-4523; visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu; or follow the museum on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.