The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded Monday, Oct. 5, to three scientists for the discovery of hepatitis C virus, an insidious and deadly blood-borne virus. One of those scientists — virologist Charles M. Rice — conducted his seminal work while on the faculty of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis from 1986 to 2000. Rice, now at Rockefeller University in New York City, was awarded the prize along with Harvey J. Alter, MD, of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Michael Houghton of the University of Alberta in Canada.

In announcing the prize, the Nobel Assembly said the hepatitis C discovery had “made possible blood tests and new medicines that have saved millions of lives.”

Rice remains an adjunct professor in the Department of Molecular Microbiology at the School of Medicine.

He described his surprise in getting a phone call at 4:30 a.m. notifying him of the award. When the phone rang, Rice assumed it was a prank call and let it go. But when the phone rang a second time, he answered. “… [T]here was a voice with a Swedish accent on the phone…When he mentioned that my friends and colleagues Harvey Alter and Mike Houghton were also being recognized with this prize, it started to sink in that it might actually be real,” Rice said during a press conference at Rockefeller University.

An estimated 71 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus infection, according to the World Health Organization. A significant number of those who are chronically infected will develop liver cancer or cirrhosis, scarring of the liver caused by long-term liver damage.

“Charlie is an absolutely brilliant scientist and a wonderful human being who has made a deep impression on all those who have worked with him,” said David H. Perlmutter, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs and the George and Carol Bauer Dean of Washington University School of Medicine. “His work on hepatitis C has improved the lives of so many people, and he represents the best of what Washington University stands for.”

Before the discovery of hepatitis C virus, physicians and researchers were concerned by unexplained cases of chronic hepatitis that developed years or decades after blood transfusions. At the time, only two viruses were known to cause hepatitis, and both had been ruled out. Hepatitis A virus does not spread through the blood, and while hepatitis B virus does, a blood test and vaccine had been developed to prevent infection.

According to the Nobel Assembly, Alter demonstrated that an unknown virus was a common cause of unexplained blood-borne chronic hepatitis, and Houghton isolated the genome of the new virus, which was named hepatitis C virus. Rice provided the critical final evidence showing that infection with hepatitis C virus alone could cause hepatitis.

The Nobel laureates’ discovery of hepatitis C virus is a landmark achievement in the ongoing battle against viral diseases, the Nobel Assembly said in a statement. “Thanks to their discovery, highly sensitive blood tests for the virus are now available, and these have essentially eliminated post-transfusion hepatitis in many parts of the world, greatly improving global health. Their discovery also allowed the rapid development of antiviral drugs directed at hepatitis C. For the first time in history, the disease can now be cured, raising hopes of eradicating hepatitis C virus from the world population. To achieve this goal, international efforts facilitating blood testing and making antiviral drugs available across the globe will be required.”

Added Rice: “Winning a prize is one thing, but the prize for all of us working in this field…is just to have been a part of going from, basically, a mystery virus to having cocktails of drugs that can eliminate the virus without any side effects in more than 95% of people. At least in my case, anything we can contribute to this comes from an intrinsic curiosity about viruses… and the chance opportunity of having an important human pathogen land in your family of viruses that you happen to be studying and go from, basically, the beginning to where it can be successfully treated. It’s a rare treat for a basic scientist.”

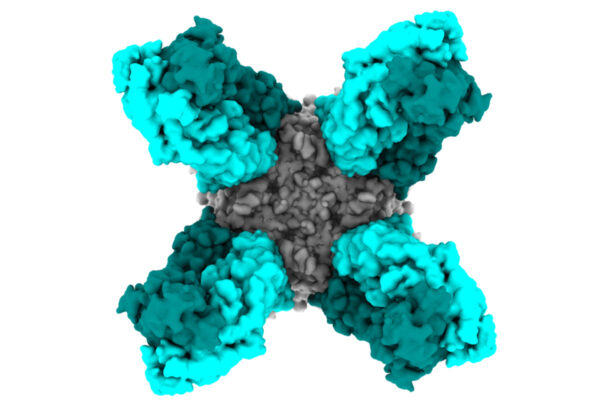

Hepatitis C virus caught Rice’s eye soon after the viral genetic sequence was published in 1989. From the sequence, it was clear that the virus was related to yellow fever virus, which he was already studying. But hepatitis C virus proved tricky. It wouldn’t grow in a dish in the lab, and it wouldn’t infect animals. One of Rice’s most important contributions was his recognition that the published viral sequence was incomplete. This breakthrough made it possible to engineer a version of hepatitis C virus capable of infecting animals and causing hepatitis. This work provided the final evidence that hepatitis C virus alone could cause the unexplained cases of transfusion-mediated hepatitis.

“At Washington University, Charlie Rice recognized that one problem in developing genetic tools to study hepatitis C virus was that we lacked the correct sequence of the viral genome,” said Sean Whelan, the Marvin A. Brennecke Distinguished Professor and head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology. “Extending on his studies from a related virus, yellow fever virus, he identified a highly conserved sequence element at one end of the viral genome. This allowed Dr. Rice to engineer a correct copy of the viral genome which turned out to be infectious in primates. This paved the way for fundamental studies of how the virus replicates, which led, ultimately, to drugs that interfere with its replication. His visionary research helped pave the way for development of a cure for HCV. He has inspired a generation of virologists.”

Rice and others went on to identify the genetic and molecular machinery the virus employs to infect cells, multiply and cause disease — all potential targets of antiviral drugs. Rice developed a system to screen drugs that block key steps in the viral life cycle, eventually leading to the development of curative drugs for hepatitis C virus infection.

Rice is the 19th scientist associated with Washington University School of Medicine to be honored with a Nobel Prize. Across Washington University, 25 current or former faculty members or trainees have received a Nobel.

“Charlie Rice is an amazing person, a spectacular scientist, and a wonderful colleague,” said Scott J. Hultgren, the Helen L. Stoever Professor of Molecular Microbiology. “He did work that led to the Nobel Prize here in the Department of Molecular Microbiology, creating the first infectious viral genome for in vitro replication. He was a phenomenal leader and colleague here at Washington University.”

Added Washington University collaborator Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine: “For many decades, Dr. Rice has been a pioneer in the field of molecular biology and genetics of many emerging RNA viruses including flaviviruses, alphaviruses, and hepaciviruses. His seminal studies on hepatitis C virus directly led to the screening and identification of direct-acting antiviral drugs that have resulted in a cure for so many people around the world. His creative research on cellular host-defense responses to viruses have triggered the development of new classes of host-directed antiviral agents. Moreover, he has mentored and trained a generation of virologists who are now at the vanguard of the field. This is truly a deserving honor for a visionary scientist.”

Born in Sacramento, Calif., in 1952, Rice received his PhD in biochemistry in 1981 from the California Institute of Technology, where he was a postdoctoral research fellow from 1981 to 1985. After his 14 years at the School of Medicine, Rice moved to Rockefeller, where he now is the scientific and executive director of the Center for the Study of Hepatitis C, an interdisciplinary center established jointly by The Rockefeller University, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, and Weill Cornell Medicine.

Rice (center) received an honorary doctor of science degree at Washington University’s 158th Commencement in May 2019. (Photo: Joe Angeles/Washington University)

He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. His previous awards include the 2007 M.W. Beijerinck Virology Prize, the 2015 Robert Koch Award, the 2016 InBev-Baillet Latour Health Prize, and the 2016 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award. In 2019, he received an honorary degree from Washington University during Commencement.