“There is a straight line between early 20th-century attitudes and policies pertaining to race and crime and current models of policing, militarization and mass incarceration.”

So argues Douglas Flowe, assistant professor of history in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. In “Uncontrollable Blackness: African American Men and Criminality in Jim Crow New York,” Flowe investigates the meanings of crime, violence and masculinity in the lives of those facing economic isolation, segregation and overt racial attack — as well as how a biased justice system surveilled and criminalized even their lawful actions.

In this Q&A, Flowe discusses the book, Black migration to fin de siècle New York and the advent of Black criminality in white imagination.

Between 1900 and 1910, New York’s Black population grew roughly 50 percent, as southern migrants fled racist violence for the promise of work up north. What conditions awaited them?

Life in New York City represented a liminal space between the sorts of violence and restriction African Americans experienced in the South and the freedoms they sought by migrating. They arrived with high hopes and a sense of determination. They had greater control over their labor; access to budding Black communities, institutions and economies; and relatively loosened racial constraints. But they also were hampered by racial segregation, job discrimination, police and citizen harassment and violence in the streets — all of which made many of their aspirations very difficult to realize.

Blacksmith Jeremiah “Lamplighter” Dunn was originally from South Carolina. What does his story tell us about access to public space?

Like many Black New Yorkers, Jeremiah Dunn migrated north in 1880 hoping to apply his trade in ways he could not in the South. But in 1895, to his frustration, Dunn was forced out of his profession by the blacksmith’s union. He then found himself laboring in a series of leisure spaces, such as bars and dance clubs, which were plentiful in African American communities and often employed Black men in low-level positions.

Working in those spaces and living in communities that hosted underground markets, Dunn experienced a lot of violence. Once, he was robbed and injured badly outside of his apartment and had to defend himself by shooting his attackers. Later, following a hostile encounter in a mixed neighborhood, he was arrested for the murder of a white man but he denied the charge and was acquitted because of a lack of witnesses.

Dunn’s story says a lot about the battle for public space. Access was dependent not only upon being able to physically use sidewalks and streets without being attacked, but also upon the ability to make a living, secure adequate housing and enjoy the city’s public culture in peace. And it is clear that the de facto and de jure constraints and regulations of Jim Crow forced Black men like Dunn into housing and work circumstances that limited their purviews, even as police and citizens patrolled the streets in ways that kept them on edge.

For those trapped between unemployment and Jim Crow, you argue, extra-legal activities could provide a sense of agency and autonomy. How did that dynamic shape emerging expectations around Black masculinity?

Like all men at the turn of the 20th century, African American men were seeking to actualize themselves as men through fulfilling work; the formation and support of families; the ownership of property; command of the public realm; and various types of leisure that confirmed their manhood.

But most normative pathways to those outcomes were blocked by prejudiced employment patterns. Black men were funneled into the hardest, lowest-paying labor. Segregation, and the system of laws and customs that supported it, literally closed doors in their faces.

My argument is that in such a predicament, when the law itself supports regulations that prevent one from utilizing the standard mechanisms of self-actualization, breaking the law, participating in underground economies, and possibly committing acts of violence can be understood as bolstering one’s sense of autonomy and, possibly, manhood. This is certainly not to say that it was standard for Black men to commit crimes or that mainstream African American understandings of Black manhood included criminal acts. But my study shows that some Black men used extra-legal methods to support themselves or their families; to feel safe on the streets of New York City; and to gain entry into the ideological and physical spaces associated with manhood.

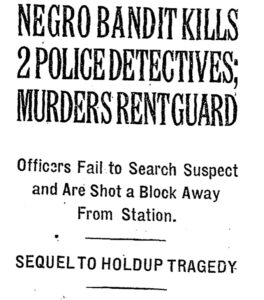

You describe the early 20th century as a “formative period in the advent of the Black criminal in white imagination.” How did popular media, and Progressive-era policing policies, influence that imagination?

The connection between Blackness and criminality/unfitness for society had formed in the white imagination long before. Indeed, it was one of the foundational beliefs of enslavement. However, in the early 20th century, we see the strong emergence of a pseudo-scientific viewpoint that many scholars believed “proved” such notions. Social Darwinists like Frederick Hoffman and Francis Amasa Walker used statistics drawn from the 1890 census, and those that came out subsequently, to make a eugenic argument that Blacks were more criminal than whites and that their lifestyles and conduct would eventually lead to their extinction.

These ideas combined with popular cultural references to Black criminals in “coon song” performances; in emerging film productions like “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915; and in a million newspaper stories that sensationalized Black crime. Like other forms of cultural production — from literature and music to minstrelsy — they seemed to corroborate the pseudo-scientific findings.

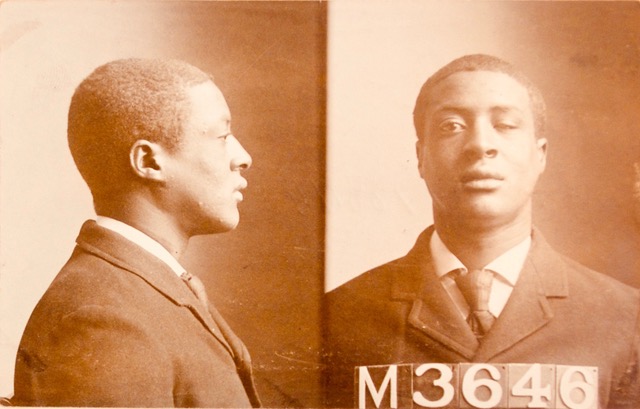

Police departments, progressive anti-vice organizations and ordinary citizens operated from the same belief system. They assumed Black criminality and treated African Americans accordingly.

Uncontrollable Blackness

African American Men and Criminality in Jim Crow New York

Do you see echoes of that history in current debates about police brutality?

Perceptions of African Americans that supported a culture of punitive policing in the early 20th century are still circulating now. The same kinds of assumptions about race and crime that justified police violence in the past underlie conservative criminological perspectives that have shaped police funding and national and local legislation since the 1960s. “Broken Windows theory” and programs like Stop & Frisk exemplify how class and race-based disciplinary postures become criminal justice policy.

“Broken Windows theory” says that policing should be pervasive, punitive and vigilant against serious and petty offenders alike. It is meant to prevent any indication of social disorder. The logic follows that if minor offenders — like loiterers, rowdy teens and panhandlers — are arrested and removed, a neighborhood’s slide into lawlessness can be prevented. Rudy Giuliani subscribed to this way of thinking when he became mayor of New York City in 1994, and his Stop & Frisk implementation largely authorized police to harass, search and detain African Americans with impunity.

Programs like Stop & Frisk primarily impact working-class urban communities and often become an arm of the broader war on drugs, which in turn has led to mass incarceration. To truly comprehend what’s feeding today’s problems, you have to understand the deep historical roots.