Despite researchers’ efforts to understand pregnancy — both healthy and high-risk — the human placenta remains something of a mystery. Tissue samples are nearly impossible to obtain until after birth, making it difficult to study the placenta’s role in pregnancy complications.

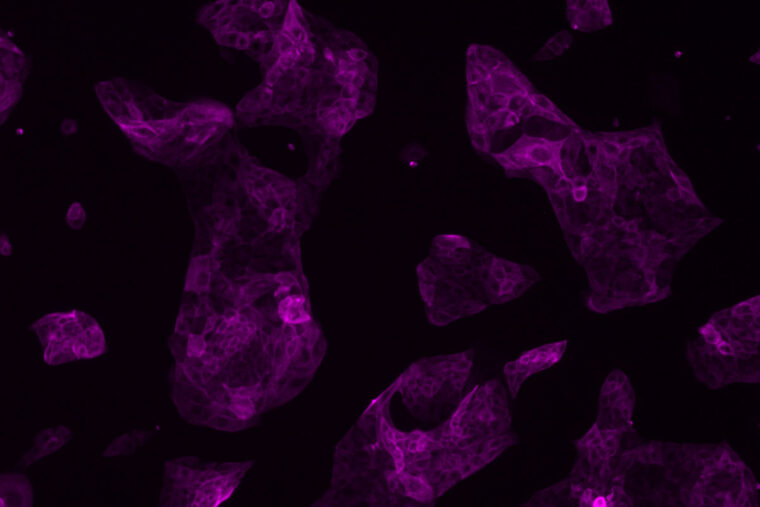

Now, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a way to guide human stem cells into becoming important precursor cells that give rise to the placenta. This advance offers a strategy to investigate the earliest stages of placental development, which could shed light on long-standing questions about miscarriage, preeclampsia and other complications of pregnancy, according to the researchers.

The study appears online in the journal eLife.

“Being able to study cells of the placenta in the lab is an important advancement because we can begin to ask very specific biological questions about pregnancy loss or other complications that have been impossible to study in the past,” said senior author Thorold W. Theunissen, assistant professor of developmental biology. “Not only does this process result in early placental cells, we showed that they can differentiate further into specific cell types that are required to support a healthy pregnancy.”

The researchers transformed human pluripotent stem cells into precursor cells — called trophoblast stem cells — that go on to form two critical cell types that make up the placenta, the study showed. One type generates hormones required to maintain a pregnancy, and a second invades the uterus, establishing routes for delivering oxygen and nutrients and removing waste from the developing fetus.

Theunissen said the new cells could be used to help understand, for example, miscarriage or a dangerous complication of pregnancy called preeclampsia, which causes high blood pressure after the 20th week of pregnancy or soon after giving birth. The condition occurs in up to 8% of pregnancies worldwide and can lead to premature birth; if left untreated, preeclampsia can cause death of the mother and the baby. While symptoms of preeclampsia typically don’t emerge until later in pregnancy, the early formation of the placenta likely plays a role in its development.

“We think preeclampsia results from inadequate invasion of trophoblast cells into the lining of the uterus and thus a failure to set up a strong enough connection — and that can result in oxygen deprivation in the embryo, for example,” Theunissen said. “What we would like to do now — with proper permission from patients — is study trophoblasts derived from, say, skin or blood samples from patients with preeclampsia or those with a history of pregnancy loss, for example.

“There are long-standing protocols that scientists use to turn an adult cell into what is called an induced pluripotent stem cell,” he said. “And from there, we could use our new process to create trophoblasts. These early placental cells developed from such patients could allow us to study — in the lab — the origins of preeclampsia or scenarios that might trigger miscarriage. In theory, we can model what goes wrong and seek ways to prevent it.”

Scientists have studied induced pluripotent stem cells in the lab for more than a decade but have not, until now, been able to use them to create placental precursor cells. The reason, Theunissen said, is that these pluripotent stem cells are in a state that exists after the embryo first attaches to the lining of the uterus. Since the placenta begins development earlier than that, even these early stem cells have already lost their ability to form placental cells.

The researchers, led by first author Chen Dong, a doctoral student in Theunissen’s lab, used a strategy they developed to turn back the clock on these conventional human pluripotent stem cells, reverting them to a pre-implantation state, one that is capable of giving rise to placental cells.

“We showed in multiple ways that these trophoblast stem cells are in fact recapitulating real human trophoblast stem cells, placental cells that were recently isolated and described by a group in Japan,” Theunissen said. “What we have done is create a much more accessible source of these cells, independent of an embryo, so that scientists can study the placenta in ways that were not possible before.”