Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Stanford University have identified a biomarker in newborns that may signal autism spectrum disorder months or even years before troubling symptoms develop and such diagnoses typically are made.

The researchers found that babies diagnosed with autism later in childhood had in their cerebrospinal fluid, as infants, very low levels of a neuropeptide associated with the disorder.

Experts believe the earlier a child is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, the sooner interventions can be started to help curb the negative effects of the disorder, such as social and communication challenges. However, autism is not easily identified before symptoms appear because there are no blood or genetic tests that can flag the condition.

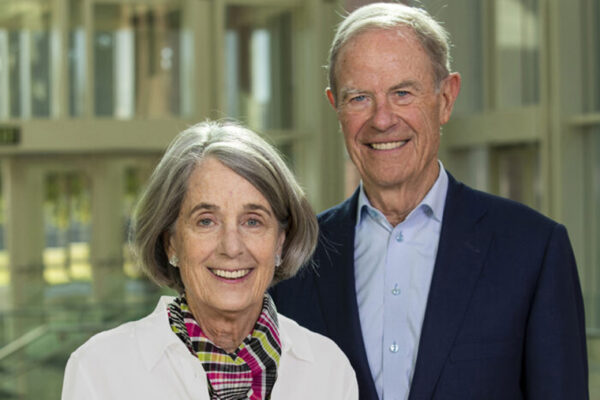

“Autism currently is diagnosed behaviorally, mainly in children ages 2 to 4 years old, but these new findings suggest we might be able to better predict which newborns will go on to develop the disorder as children,” said co-senior investigator John N. Constantino, MD, director of the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Washington University. “This neuropeptide biomarker long predates clinical symptoms, and if confirmed, it could allow us to begin interventions much earlier in children who will go on to develop problems, further opening the possibility of pharmaceutical strategies to increase neuropeptide levels and, potentially, to prevent some problems associated with autism.”

The new study is published the week of April 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

For this study, the researchers examined cerebrospinal fluid samples collected during from a large cohort of feverish newborns cared for at St. Louis Children’s Hospital two decades ago. The scientists determined that babies whose samples had very low levels of the neuropeptide were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with autism later in childhood.

Neuropeptides are short chains of amino acids. Levels of the neuropeptide identified in the study — arginine vasopressin — already are suspected to be lower in children with autism.

Constantino, the Blanche F. Ittleson Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, said that variations in arginine vasopressin and oxytocin, another hormone, have been associated with autism spectrum disorder, but this study offers the first evidence that levels of one of the hormones are abnormal so early in life. Measuring the neuropeptide may provide an indicator of which children are at highest risk of developing autism, he said.

The study involved 913 newborns with fevers whose cerebrospinal fluid was examined for markers of meningitis but who were found to be negative. The leftover spinal fluid was saved and stored. Included in those samples was cerebrospinal fluid from nine children who went on to be diagnosed with autism. The researchers compared those nine samples to samples from 17 age- and gender-matched children who were never later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.

The nine children diagnosed later in childhood had significantly lower levels of arginine vasopressin when they were infants than the 17 who did not go on to be diagnosed with the disorder.

“This new biological clue from a rare and unprecedented collection of newborn human spinal fluid samples needs to be pursued in larger numbers of children,” said the study’s other co-senior investigator, Karen J. Parker, associate professor and associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford. “Given the alignment of these findings with studies in older children and in nonhuman primates, we want to understand why this neuropeptide might have such a marked, predictive association with the development of autism spectrum disorder because it appears to be extremely predictive of future risk.”

Parker and Constantino are planning a larger study to collect cerebrospinal fluid from newborns and measure levels of their neuropeptides to see whether the findings from this smaller study can be replicated.

Measuring these biomarkers, while tracking a baby’s eye movements, motor impairment, hyperactivity syndromes and other risk factors for autism, could give doctors a clearer picture of which children are at the highest risk to go on to develop autism and allow interventions much earlier in life.

Meanwhile, in a separate study, Constantino also has found that a feared indicator of autism risk to babies has been overestimated. A number of family and genetic studies over the past decade have generated a theory that the pronounced 3:1 male-to-female sex ratio in autism is due to a “female protective effect.” In other words, females may be relatively protected from autism compared with males, even though both males and females have similar genetic susceptibility.

The theory has generated widespread concern that the unaffected sisters of individuals with autism may have a high likelihood of transmitting genetic risk for autism to their sons.

Together with researchers from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai in New York and the Chinese University in Hong Kong, Constantino analyzed data from a large, two-generation population registry in Sweden to provide the first-reported estimates of risk among the offspring of adults who are siblings of a person with autism.

The researchers found that the children of sisters of individuals with autism are not significantly more likely to be affected by the disorder than the children of brothers of individuals with autism. The risk for both is 2% to 3%, or about 10 times lower than had been feared for sisters. The Swedish study, published online April 2 in the journal Biological Psychiatry, involved nearly 850,000 children born from 2003 through 2012.

“The findings suggest that the autism sex ratio is more a function of males being more sensitive to genetic susceptibility factors for autism, rather than females being protected,” Constantino said. “That has important implications for the design of studies that look for the factors that result in the disproportionate risk for autism and related developmental disorders in boys.”