What are two political scientists, including one from Washington University in St. Louis and his pal from Princeton University, doing with a Harvard University-based team to try to determine if music is indeed universal?

Why, analyzing the statistical data, of course. Or, as Elvis Presley — mentioned in their research paper — might have been mistaken to croon about one of their accompanying graphs: Lay off their blues’ weighed hues.

Christopher Lucas, assistant professor of political science in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, and his former graduate-school roommate, Dean Knox of Princeton, were asked by Harvard principal investigator Sam Mehr to aid an interdisciplinary team including psychologists, anthropologists and evolutionary biologists with an intensive data examination of music’s universality.

“We took all this unstructured data, the ethnography of songs and the actual recordings of the songs themselves, and figured out: How can we structure this and turn it into something we can analyze?” Lucas explained.

Lucas remembered Mehr joking: It will probably take you two weeks.

Two years later, the analysis resulted in a painstaking, meticulously researched paper published Nov. 21 in Science titled “Universality and diversity in human song.”

This deep dive into song also helped to create the National History of Song (NHS) Ethnography.

“It’s a significant project,” Lucas said. “Exceptionally difficult. The data collection was very big. For the analysis, about 10,000 lines of codes were written. Dean and I were in there, doing the actual statistical analysis of the paper.”

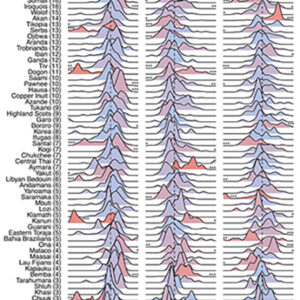

This involved examining 315 societies across the planet, for which all but six were found in ethnographic documents listed in the Human Relations Area Files organization. The other six societies — Dominican, Ghorbat, Hazara, Pamir, Tajik and Turkmen — were listed elsewhere.

Amid what Lucas called “a very diverse set of intellectual homes” — three continents and 11 institutions included among the 19 collaborators and hundreds of other musicologists and ethnomusicologists and online voters used in this project — the charge for Lucas and Knox remained simple. They compiled and crunched data, including nearly 500,000 words gleaned from song descriptions across those 315 societies.

“The general theme of our research is developing statistical methods to measure things that aren’t typically seen as data, like sound — including human speech,” Lucas said, mentioning a separate research project that is currently under review and available online. “What we’ve decided to focus on at WashU is computational analyses, and it’s what we’ve gotten good at. I guess you wouldn’t imagine political scientists on the team to analyze music — but here that’s one of our bread-and-butter things. Everything we do can be analyzed as data.

“Twenty years ago in political science, you studied polls and votes,” Lucas continued. “Today, we study the way politicians talk, the audio recordings, the way people are affected. … The tools we’ve developed to study that in politics have a lot of punch when applied elsewhere, too.”

So this project asked the question: Is music universal? “What that means is, are there similarities in the social contexts and auditory structure of song across different cultures?” Lucas said.

Their data helped to show: From the Arctic to the Amazon regions, from the Akan (the most religious society) to the Kanuri (least formal), song is a human’s behavioral response as much as an affinity for a music or genre, and it cuts across all cultures and societies.

The interdisciplinary team discovered clusters, among three major principal components: Formality, Arousal and Religiosity. Dance songs (1,089 excerpts) fell into the high-Formality, high-Arousal, low-Religiosity area. Healing songs (289 excerpts) carried the same first two characteristics but were high-Religiosity. Love songs (254 excerpts) were low in all three. Lucas and Knox analyzed the data and found that, though different societies did have certain unique elements, they also had more in common with one another than expected. A globally average song would not appear out of place in any society.

“Our article finds universal patterns in vocal music — both the social contexts in which it occurs and the auditory structure of the song,” said Knox, an assistant professor of politics at Princeton. “These patterns are similar across hundreds of small-scale societies. Among other results, we show that machine-learning techniques can reliably recognize the social function of a song — i.e. dance songs, healing songs, love songs, lullabies — even without knowing anything about the culture or region that created the song, based only on patterns learned from other societies.”

“Music is probably the most unique domain we’ve worked in,” Lucas said of his work alongside Knox. “There’s no blueprint, but we had to think of what are the tools that we know that could address this problem. It’s not as easy as seeing a nail and grabbing a hammer. It’s seeing a screw and figuring out how to work with it.”

No, that doesn’t mean he was listening to MC Hammer or Pete Seeger’s “If I Had a Hammer.”

Lucas admitted that while working on this project’s data, he was tuned into Led Zeppelin.

“I did listen to them. Quite a lot,” he said. “They should be in the paper’s acknowledgements.”