In critically ill patients who require a heart pump to support blood circulation as part of stent procedures, specific heart pumps have been associated with serious complications, according to a new study led by cardiologists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Though the observational study does not prove that the heart pumps — ventricular assist devices — are the cause of complications, it suggests that with current practice patterns, there is an association between the use of the pumps and an increased risk of bleeding, kidney problems, stroke and death in patients undergoing stent procedures. The study authors are calling for more research evaluating the heart pumps marketed under the brand name Impella.

Results from the study were presented Nov. 17 at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2019 in Philadelphia and published simultaneously in the journal Circulation.

After statistically adjusting for certain variables, the researchers found an increased risk of death, bleeding, acute kidney injury and stroke among patients while they were still hospitalized after receiving Impella pumps versus balloon pumps. In particular, the Impella pump was associated with a 24% higher risk of death than seen with balloon pumps and a 34% increased risk of stroke compared with the balloon pump. Both of these differences are statistically significant. In no category was the Impella pump associated with improved outcomes.

“These results deserve a closer look to try to better understand the link between the device and its complications,” said lead author Amit P. Amin, MD, a Washington University cardiologist and associate professor of medicine, who is presenting the data. “They suggest that perhaps a more measured approach — one that balances risks and benefits — is needed in this critically ill population. These data are observational, so they can’t prove causation. But they underscore the need for large, randomized clinical trials and prospective registries to better understand and guide the use of cardiac support devices.”

The researchers analyzed data from the Premier Healthcare Database that included information from 48,000 patients treated at 432 U.S. hospitals. Each patient in the study underwent a heart stent procedure, which involves opening a blocked artery in the heart to improve blood flow. Some patients undergoing the stent procedure are seriously ill, often having other medical conditions including heart failure, low blood pressure, complex blockages and other cardiac problems that might lead doctors to decide to add a mechanical assist device during the procedure to help the heart pump a greater volume of blood. Of the patients in this study, just under 10% (4,782 patients) received an Impella heart pump. The remaining 90% (43,524 patients) received an intra-aortic balloon pump.

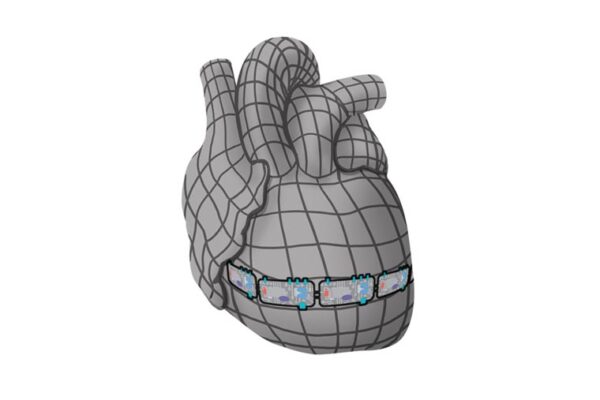

Most patients undergoing stent procedures don’t need a ventricular assist device. This study is focused on the small segment (roughly 3% to 5%) of patients undergoing stent procedures for more advanced heart problems — such as complex blockages or heart failure or cardiogenic shock, in which the heart loses its capacity to pump sufficient blood — and need a ventricular assist device. Most patients receive an intra-aortic balloon pump, which rhythmically inflates and deflates in coordination with the heart’s natural rhythm, to help push blood through the vessels. These pumps have been in use since the 1960s. But since 2008, a steadily increasing proportion of patients receive the more recently approved Impella pumps, which have small rotors that create a continuous flow of blood.

The data came from patients treated from 2004 to 2016. The Impella pump was introduced into clinical practice in 2008, allowing for comparisons from the time periods before and after this type of pump came into use. Impella use increased steadily from about 1% of patients receiving a pump in 2008 to almost 32% of all patients in 2016 undergoing stent procedures with support devices.

The researchers also found large variations in how often hospitals used Impella pumps. The hospitals that used Impella pumps more frequently had higher adverse outcomes, as well as higher costs associated with caring for these patients, despite controlling for clinical factors. The researchers analyzed the possibility that sicker patients were more likely to receive the Impella pump, perhaps explaining at least part of that association. Instead, they found a trend showing lower Impella use among more critically ill patients.

The authors caution that there are limitations to this observational study, such as physician preference for use of Impella or balloon pumps, or inability to account for factors that were not measured in the observational study. But since the majority of the data suggest no improvement in outcomes linked to the use of the Impella pump as well as serious complications, Amin and his colleagues call for more definitive research to better understand the appropriate role for circulatory support devices in clinical practice.

“These mechanical support devices are innovative and can efficiently pump blood to the body, but in this study, we found no association with improved outcomes with the Impella pumps,” Amin said. “This warrants more study so we can understand which patients are likely to benefit from these cardiac assist devices and which are more likely to develop problems.”