For some, it is written in artifacts. For others, truth can be found in cool, hard genetic code.

Both kinds of data factor into an ambitious new study that reports genome-wide DNA information from 523 ancient humans collected at archaeological sites across the Near East and Central and South Asia. Washington University in St. Louis brought key partners to an international collaboration of more than 100 scholars who gathered archaeological skeletal samples — and pooled their expertise — to generate the largest study of ancient DNA published to date.

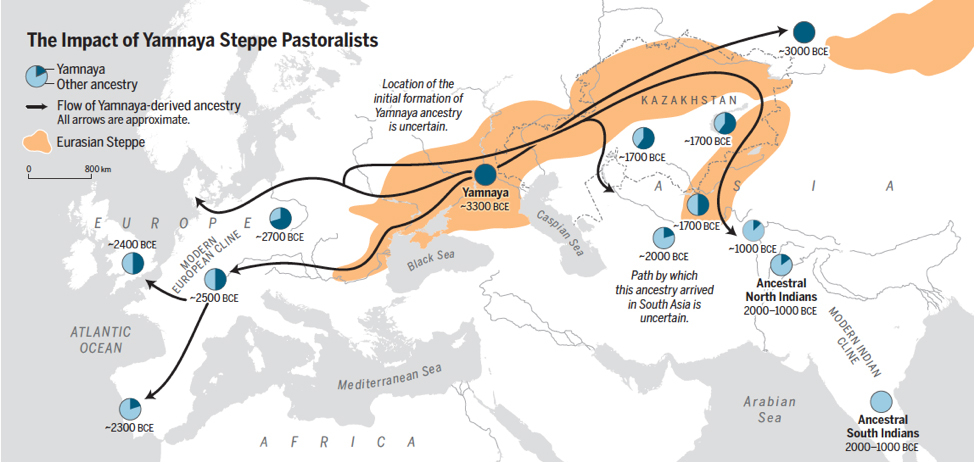

Their results, published this week in the journal Science, link the genetic and linguistic makeup of populations of Eurasia and India to the ebb and flow of people and cultures between 12,000 to 2,000 years ago that transformed Old World populations and civilizations.

“Often people assume populations change through simple migration processes, but regional genetic formation is nuanced, long-term and dynamic,” said Michael Frachetti, co-senior author of the study and professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.

“In some cases, we see centuries of regional mobility alongside stochastic population movements. We also document cases of prolonged, multidirectional interaction. Often, it’s all of the above,” Frachetti said. “So we made every effort to combine deep archaeological knowledge with the DNA results to illustrate how different mechanisms produced genetic diversity and change at different times.”

Locking down the story

As the tools and methodologies for harvesting and analyzing DNA from bone samples improved and became more accessible, archaeologists and geneticists started to reshape the nature of their partnership in studying ancient societies.

“Early on, archaeologists were critical that ancient DNA studies were crafting huge narratives from limited data. That was a real limitation of early work, and I, too, had my concerns,” Frachetti said. “This project was conceived to explicitly merge different methods and kinds of expertise, thus our approach was intentionally more inclusive of numerous voices in hopes of getting the best possible results.”

Years in the making, the conceptual framework behind this research was sparked by David Reich, professor of genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Broad Institute and Vagheesh Narashimhan, a postdoctoral scholar in his lab; Nick Patterson, a computational biologist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; Ron Pinhasi of the University of Vienna; and Frachetti. Their collaborative group grew to include dozens of archaeologists and geneticists around the world.

By focusing on Central Asia, the research addresses a huge gap in the world’s ancient DNA dataset — which was almost entirely restricted to Europe.

Said Reich: “The idea for this study grew out of a meeting we had in Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y., in May 2016, which was equally organized by geneticists and archaeologists. The goal of this meeting was explicitly to break down barriers between disciplines and find ways for these two communities with so many shared questions but different world views to come together.

“Michael’s perspectives were challenging and stimulating to us geneticists. After multiple intense conversations, he and Ron Pinhasi and I decided to develop an ancient DNA study that was explicitly framed by Michael’s archaeological questions, that would take advantage of innovations in ancient DNA technology that made it possible to massively increase the number of samples we could study, and that by focusing on Central Asia would address a huge gap in the world’s ancient DNA dataset — which until then was almost entirely restricted to Europe.”

The result is a study that in one fell swoop increases the worldwide total of published ancient genomes by about 25%, and that shifts the center of gravity of the world’s ancient DNA dataset far to the east.

“It’s a significant addition to the literature,” said Narasimhan, co-first author of the study. “We’ve been able to process and analyze samples at a scale that hadn’t been possible before.”

Added Pinhasi, a co-senior author: “We combined a wide range of approaches: linguistic data, archaeological data, modern-day genetic data and ancient DNA data. The new findings about the origins and spread of the Indo-European languages, in particular, highlights the power of studies that combine data, methods and perspectives from a diverse range of disciplines.”

Frachetti has worked for over two decades in Kazakhstan and at archaeological sites linked to the Great Silk Road, the ancient trade route between China and the Mediterranean. Frachetti led much of the skeletal sampling for the Science paper; his close relationships in the region helped in developing ethical collection partnerships with colleagues and institutions across Central Asia.

“For decades, local archaeologists have been working to provide nuanced pictures of the underlying forces of social complexity and organization,” Frachetti said.

“This study shows the explanatory power of relying on local scholars to help build the genetic datasets and shape the important questions on a variety of scales — from individual excavation sites and individual specimens to wider, macro-regional narratives. It’s a great example of how these collaborations should work.”

“The history of Central Asia shows that connected ancient societies innovated rapidly due to exchanges of technology and ideas, whereas more isolated groups often faced longer-term economic stagnation. Likewise, current developments in academia benefit from active international exchange,” said Farhod Maksudov, a study co-author and director of the Institute for Archaeological Research of the Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences. “For scholars from Uzbekistan (and likely other Central Asian countries), international academic collaboration is essential — this study, which significantly advances our knowledge of Central Eurasia’s deep history, shows the power of academic connectedness and cooperation on a large-scale.”

A new dimension for work at Dali

Roughly 5,000 years ago, as the spread of herding required the movement of animals between summer and winter pastures, farmers and nomads came into greater contact across the region.

“Our maps in this study illustrate how transcontinental gene flow evolved over vast territory and thousands of years, but one must be careful not to view these genetic arrows as colonial invasions — in fact, our data show that human mobility typically brought about gradual change over the span of centuries, and sometimes millennia,” Frachetti said.

This new genetic information adds another dimension to human histories previously informed by archaeological work at particular sites.

A perfect example of this comes from an ancient site in Kazakhstan, where Frachetti has been excavating for many years.

Known as Dali, the mountainous site is located near the crossroads of cultural and genetic change during the Early and Late Bronze Age in a region that Frachetti calls the Inner Asia Mountain Corridor. At Dali, student researchers participating in the Washington University archaeological field school excavated skeletal samples that are a key part of the current ancient DNA study.

The genetic results from burials at Dali show movement and admixture between groups with North Eurasian hunter gatherer ancestry and farmers from the Iranian plateau — defining a bi-directional flow of ancestry along the mountains and steppes of Eurasia approximately 5,000 years ago.

Separately, Frachetti and collaborators also sampled DNA from individuals of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (or BMAC), a Bronze Age civilization of southern Central Asia, found in present-day Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, which was discovered for the first time in the 1970s by Soviet archaeologists.

Within the large number of samples from the BMAC included in the new genetic study (more than 100 individuals where previously there was no data), researchers were able to identify several key “outliers” — individuals who reflect early steppe genetics, similar to those found at Dali — living among an otherwise homogenous group.

The discovery of a range of these genetically distinct individuals intermixed among regional populations fits with the archaeological evidence collected by Frachetti and his students over the past decade. They previously had determined that people in the large urban centers of the BMAC were trading goods with pastoral communities living along the mountains and nearby plains.

“We had made the argument, as did many others, that steppe pastoralists were interacting with the BMAC on the basis of ceramics, metals, etc.,” Frachetti said. “But there wasn’t enough research, and the data were few. The new information we are getting from ancient DNA is critical to understanding the complex connectivity between these diverse communities across Asia.”

“What we see in both in the isotopic information as well as the archeological information is trade and exchange of agricultural material and production happening in both directions: north and south along this corridor,” Harvard’s Narasimhan said.

“Now with the ancient DNA, we’re actually seeing that in the people,” he added. “It’s giving us confidence to understand what happened in the past and how this process is happening.”

Vivid narrative

The new genetic results also open up a wide array of additional questions that archaeologists can now probe with new eyes.

“The sort of questions you can ask now — the sky’s the limit,” Frachetti said. “Working with this team has definitely opened up new ways of thinking for me. Questions about the degree to which trade and exchange versus important population movements brought innovation to various peoples, and how it shaped their future directions.”

“I’ve asked a lot of these questions for 25 years without the benefit of the genetics,” Frachetti said. “So, it’s exciting to return to my laundry list of questions and say, ‘Wow, a lot of these are now made that much more crystal clear.’”

The power of this study comes from its breadth and reach, made possible by samples from so many contributing archaeologists.

“If you only have one archeologist help to tell the story, then likely that one might be inclined to support his or her own theories,” Frachetti said. “But if, for example, you bring together data and ideas from 10, 20, 50 archaeologists — many of whom have different, competing theories on the same topic — it forces everybody to look at the science, and that’s how progress is made!

“That’s really why teaming up with geneticists is so important. It’s still not totally perfect in terms of how everyone wants things to be explained,” Frachetti added. “But this paper brings us a rigorous, well-designed study with a massive baseline of ethically acquired data. Now all scholars can go back to it to focus on different sites or see how the data fit into their archaeological interpretation.

“This study, and the important genetic record it establishes, allows us to shade in the narrative so much more vividly,” he said.