Pick your chicken wisely. The choice could make or break your marriage.

For generations, household farmers in the Horn of Africa have selectively chosen chickens with certain traits that make them more appealing. Some choices are driven by the farmers’ traditional courtship rituals; others are guided by more mundane concerns, such as taste and disease resistance.

The result is the development of a genetically distinct African chicken — one with longer, meatier legs, according to new Washington University in St. Louis research published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. But that 3,000-year-old local breed type is threatened by the introduction of commercial cluckers.

This study contains the first metrical baselines of chickens with known history in the region, and it reveals much about the history of the selection process and African poultry development, said Helina S. Woldekiros, assistant professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences.

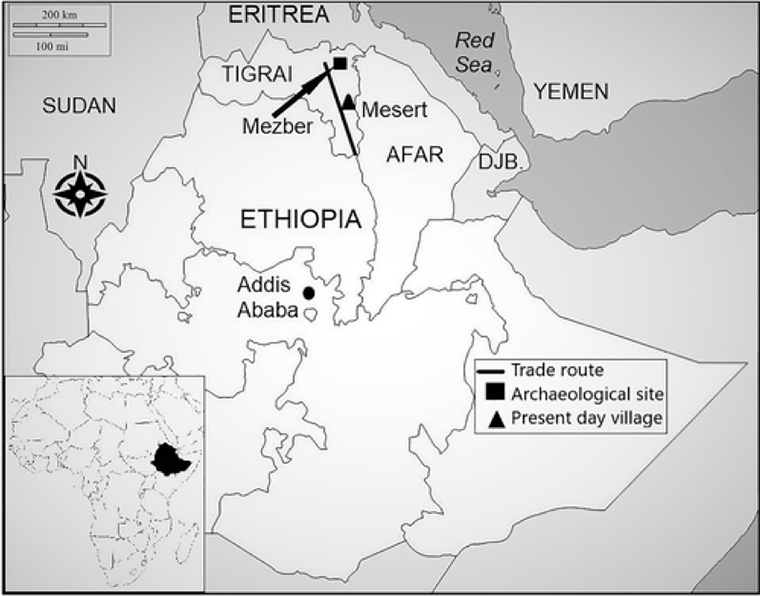

For this new work conducted in collaboration with researchers from the Universities of Exeter, Leicester, Nottingham, Oxford and Roehampton in England, Woldekiros returned to a community in northern Ethiopia near where she previously discovered some of the oldest known physical evidence for the introduction of domesticated chickens to the continent of Africa.

“I’m a bone person, so I’m mostly interested in how much change there was between the archaeological chickens and the modern ones,” Woldekiros said. She already had measurements from the ancient chickens in her original find. So she approached 20 families in the small village of Mesert to ask if she could survey their chickens before a Christmas celebration — then processed all the bones after the chickens were eaten.

In addition to the earliest domestic chickens in Africa and today’s African local chicken breeds, the study includes the red junglefowl — a wild chicken found only in Asia — using bones from a collection curated at the Natural History Museum at Tring, England, northwest of London.

By comparing measurements from these three types of chickens, Woldekiros collaborated with her colleagues from the U.K. to identify key differences that provide insight into African poultry development over the centuries.

“African farmers were selecting for longer limbs,” Woldekiros said. “They were looking for more meaty legs, rather than meaty wings. There was a big change in the length of the legs.” The earliest domesticated chickens, dating from 800 BCE to 400 BCE, were also much closer total body size to today’s red junglefowl than to the modern household chicken.

African chickens are a primary source of protein for the farmers with whom Woldekiros works. Most Mesert families keep between five to seven birds at any given time. Locals prize certain physical attributes like colorful shank feathers and elaborate comb patterns. But Woldekiros is concerned about a trend that she has been observing while she conducts her fieldwork.

“Right now, exotic and commercial chickens are being introduced to Africa, and local African breed types are in danger,” Woldekiros said.

“They are more biologically diverse than the exotic or commercial birds,” she said. “Now we are in danger of losing that diversity.”

The new chickens might be more productive — but it comes at a cost.

“The problem with the new chickens, even though they produce more meat and more eggs, is that they’re really expensive to keep,” she said. “You need to build a shelter for them, so they can’t scavenge like local birds. And they’re very sensitive to disease.”

These costs weigh particularly heavily on widows and single mothers for whom chickens have traditionally been a good source of income, because they were so inexpensive to keep, she said.