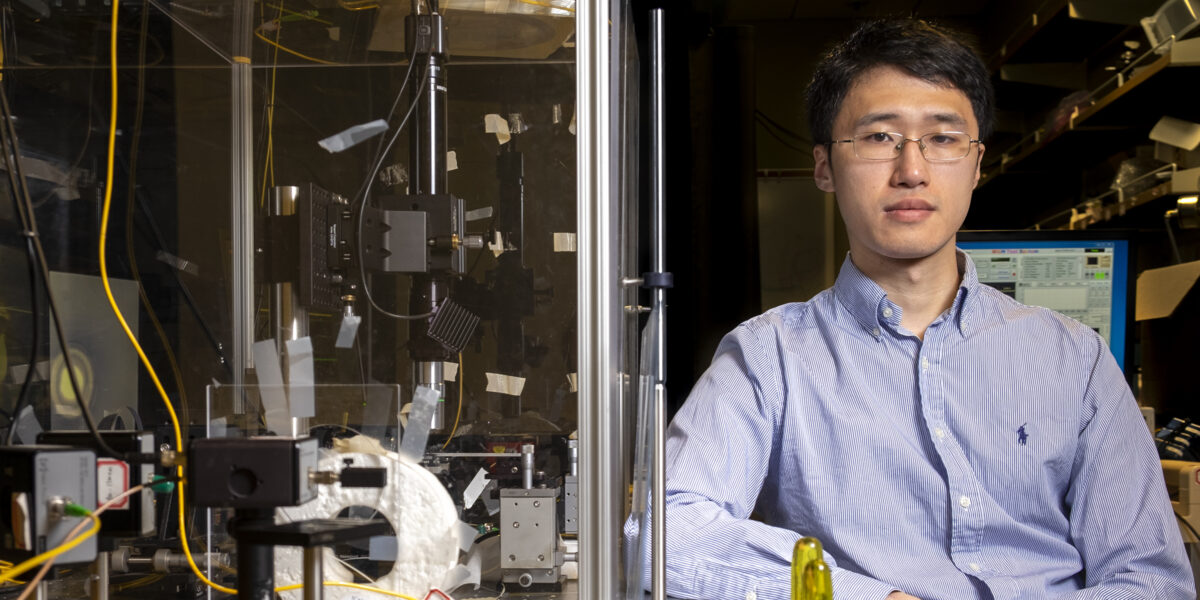

Guangming Zhao says it repeatedly: “I’m just a normal person.” He doesn’t understand why anyone would be interested in talking to him, a 29-year-old PhD candidate in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, who just wants to create the best imaging sensor in the world.

And there’s a good chance he’ll be successful.

And there’s a good chance he’ll be successful.

“At first, I didn’t believe it,” he said of the research’s potential to impact the world around him. “But now I do believe it. I believe that what we do here can change the world.”

Zhao is working on new technology that uses light to probe its surroundings. Used in different instruments, the photonic sensors could detect anything from poisonous gases to bloodborne diseases.

He attributes his change in perspective to working in the lab of Lan Yang, the Edwin H. & Florence G. Skinner Professor of Electrical & Systems Engineering. Since working with her, he said, he has had a few changes of heart.

When he joined Yang’s lab in 2012, Zhao considered himself a physics guy. “I wanted to focus on fundamental science,” he said. Zhao wasn’t concerned with practical applications. When Yang proposed he work on the photonic sensors, he wasn’t exactly thrilled.

“Dr. Yang said it was interesting, but at first I disagreed,” Zhao said. “I said, ‘I like fundamental science.’ When I really accomplished something, though, I saw it was worth it.”

Zhao has pushed forward the science of the sensors, which have successfully recorded temperature data while mounted on a drone. The photonic sensors — which are based on light instead of electricity — may also greatly increase the sensitivity of ultrasound technology, an industry estimated to be worth $7.2 billion by 2022.

“In the ultrasound arena, this technology has the potential to be a breakthrough,” said Anand Chandrasekher, an industry adviser who came across Zhao’s research through a mutual friend of Yang’s. He is now helping lab members determine if they are ready to transition their technology from the lab to the marketplace.

Chandrasekher has been in the semiconductor industry for 30 years. From president of Qualcomm Datacenter Technologies Inc. to seeking out technology transfer opportunities in university labs, he has seen all sorts of people come and go.

“(Zhao) is in a league of his own in terms of perseverance, creativity, objective analysis,” Chandrasekher said. “He’s not a BS artist; he says what he means, does what he says, and he gets it done.”

Although they can’t reveal the precise nature of Zhao’s contribution to the sensors as they continue to research their viability as a product, Chandrasekher is clear when it comes to Zhao’s importance: “Let’s just say that without him, there is no company.”

For now, however, Zhao remains dedicated to his work in the lab. In fact, he could have graduated a couple of years ago.

“When my fifth year came, Dr. Yang asked, ‘Do you want to graduate?’ I refused to graduate,” he said laughing. “I wanted to finish what I started.”

That perseverance is one of the qualities that sets Zhao apart, according to Yang.

“He could face 100 failures and keep going,” she said, recounting the time she saw him in the lab well past midnight. It’s possible that someone else could have developed these sensors, “but everyone said it was impossible. Zhao, however, did not give up.”

A chance to study with ‘one of the best’

The road to St. Louis began for Zhao in Tianjin, a city of 13 million people about 35 miles south of Beijing. He attended college at the University of Science and Technology of China — Yang’s alma mater — where he majored in optics.

And there’s a simple reason he came to Washington University. “Dr. Yang is here,” he said. “She is one of the best.”

Studying so far away from home can be challenging; Zhao has only been home twice and his parents have visited once. They liked St. Louis almost as much as he does.

“Washington University is a really good place for research,” he said. “I really like it here — the students, the teachers, the people here,” he said, gesturing to those around him in nearby Kayak’s Coffee.

Zhao’s modesty is apparent in his incredulity at the idea that anyone wanted to interview him. His kindness was apparent in his offer to run home and fetch an umbrella for his interviewer when a downpour hit at the end of the interview.

“What I value most about him, while he says he’s normal, I look inside his heart, that’s what matters,” Yang said. “He just wants to do good work. Money will not move him.”

Zhao’s goal is straightforward: “I want to have the best sensor in the world,” he said. He hopes it will ultimately be able to detect diseases that current ultrasound machines can’t.

“We can help people in the medical school, and maybe also help patients. Our sensor also has a low cost and high sensitivity,” he said. “So we may really change the world. At first, I didn’t believe it, but now I do think we have a chance to do that. To help people.”

When he first arrived in St. Louis, Zhao was a physics guy interested in blue-sky research. “At first, I just wanted to learn some things,” he said. “Later on, I learned something from my mentor. I realized that I need to have a sense of mission and a duty as a researcher.

“So we do research to help people. I think all researchers should realize that.”