In 1963, as public school desegregation battles raged across the South, three of the nation’s most prominent black leaders — Martin Luther King Jr., Julian Bond and Ralph Abernathy — quietly sought to enroll their own children in several of Atlanta’s most prestigious private schools, elite K-12 institutions, which, until then, had managed to remain all white.

“Our sole purpose in making application,” King stated at the time, “for our son, Martin III, was a sincere attempt to secure for him the best possible secondary education. This was not meant to be any sort of a test case, though we do desire for our son the experience of integrated schooling.”

While King may not have intended the application to be a test case, the school’s decision to deny admission would bring added momentum to forces pushing for the desegregation of elite private schools in Atlanta and elsewhere, suggests Washington University in St. Louis’ Michelle A. Purdy, author of a new book on the young blacks who broke the color barrier at the South’s most prestigious private schools.

The stories of these first black students remain important, Purdy argues, because lessons learned through their experiences are precursors to present efforts to foster diversity and inclusion within private schools and universities.

“In some ways, the book captures the mixing of worlds at a pivotal time in U.S. history because the mixing occurred both voluntarily and, in some ways, involuntarily,” said Purdy, assistant professor of education in Arts & Sciences. “It explores issues of race and identity, diversity and inclusion, education and equity that are as important now as they were then.”

While many historians have explored the bitter court-ordered desegregation of public schools following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, the equally dramatic story of the voluntary desegregation of prestigious, traditionally white, private schools remains largely untold.

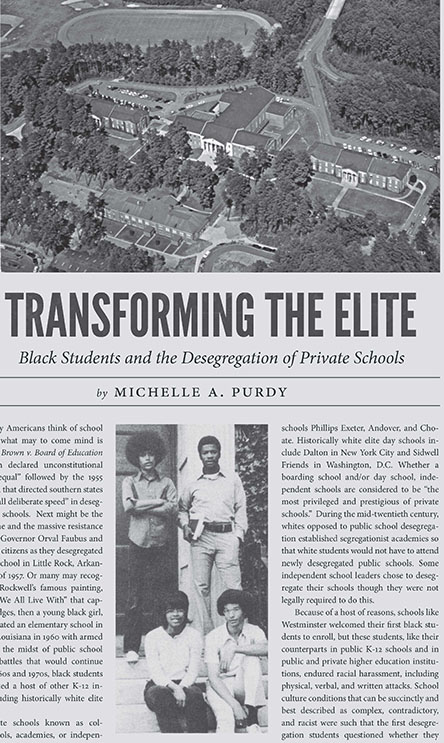

Purdy’s book, “Transforming The Elite: Black Students and the Desegregation of Private Schools” (University of North Carolina Press, 2018), sets out to fill that void.

Focusing on the experiences of the first black students to desegregate Atlanta’s well-known The Westminster Schools, the book combines social history with policy analysis to recreate this overlooked history. It explores the political and social forces (and threats to tax-exemption) that led these schools to “voluntarily” embrace desegregation during the late 1960s and early 1970s, even as court-ordered desegregation was being bitterly contested in public schools.

Based on archival research and first-person interviews with former students, Purdy explains how and why elite private schools chose to embrace more black students and how that decision shaped the lives of the young black students who navigated entrenched racism on both institutional and personal levels.

While Westminster was not the first private school to desegregate, it was one of the first nationally recognized schools to face the desegregation challenge in the South. Its prestige and its location in Atlanta set the stage for it to become an influential national leader in private school desegregation.

With a sprawling 180-acre suburban campus and now one of the largest private school endowments in the nation, Westminster long has been an attractive option for Southern families who did not want to send their children to more established boarding schools in the Northeast. Located among luxurious homes in Atlanta’s Buckhead neighborhood, the campus was distinguished by its white columns, grand double staircases and vaulted ceilings.

In the early 1960s, Atlanta was itself struggling to establish a new identity. Headquarters to huge corporations such as Coca-Cola, the city billed itself as the “unofficial capital of the New South” and “the city too busy to hate.” Atlanta was eager to avoid the violence that had marred desegregation efforts in other cities, but its culture remained rooted in white Southern traditions.

For King, Bond and Abernathy, all residents of Atlanta and leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Council in 1963, their efforts to break the private school color barrier ended with mixed results.

Breaking the barrier

Martin Luther King III was denied access to Atlanta’s Lovett School, causing a rift that led the school to sever its ties with the Episcopal Church, an early proponent of integration. Abernathy’s daughter was unable to pass the admission test to Atlanta’s Trinity private school, but Bond’s daughters were eventually accepted for enrollment there in the spring of 1963.

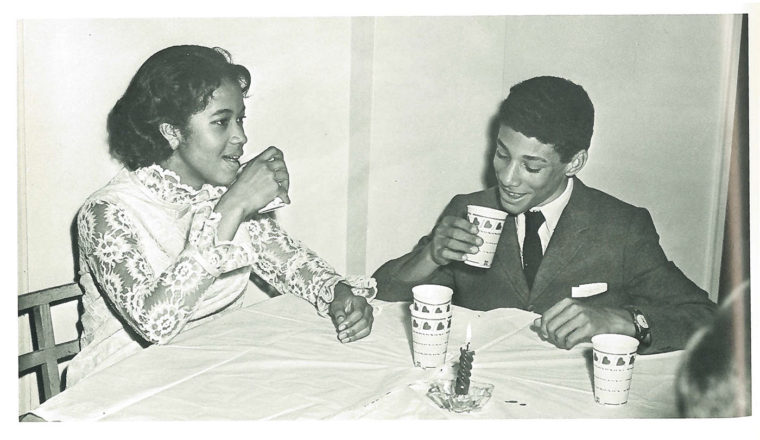

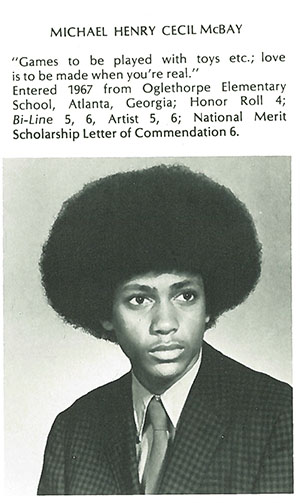

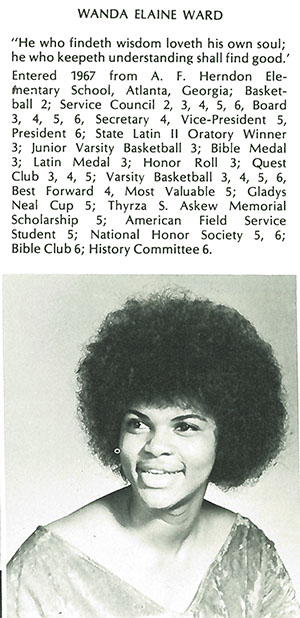

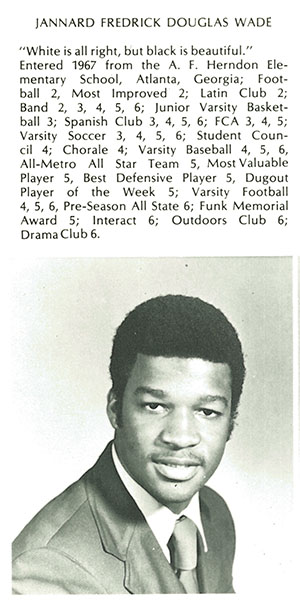

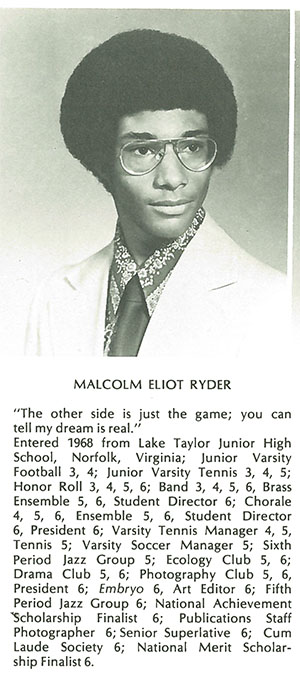

At Westminster, the color barrier would be broken not by the children of prominent black civil rights leaders, but by a small band of young black men and women from middle-class families who began there in the fall of 1967: Bill Billings, Dawn Clark, Isaac Clark, Janice Kemp, Michael McBay, Jannard Wade and Wanda Ward.

Most of the “fearless firsts” came from families with well-educated parents, including some that worked as teachers at local black colleges and schools. The products of strong education in Atlanta’s segregated black elementary schools, several had scored well enough on admissions tests to be offered scholarships from the Stouffer Foundation, a fund started by a Reynolds tobacco heir to support the education of young black men.

While Westminster opened its doors to black students, some white students were less than welcoming.

On his first day, McBay was forced to hide in the bathroom after being teased and harassed by a group of white students he believed to be football players. Other white students made a habit of putting the empty exoskeletons of emerged locusts (cicadas) in his hair, laughing when he had difficulty removing them from his afro.

The first black students arrived in an atmosphere still dominated by white Southern traditions, including a fall dance in which the school was decorated as a plantation and male students encouraged to dress in Confederate uniforms. The school’s annual Christmas Fund Drive included a slave auction fundraiser.

When the school decided to desegregate its women’s dormitory for the first time in 1970, it told white students to arrive a day early so they could be warned that two black girls would soon join their ranks. The black girls “were different,” they were told, but they should not be “afraid.”

Still, the school’s administration, at times, did its best to make institutional changes to support the desegregation process. It fired the school’s football coach after he used a racial slur to urge the team, including Wade, its first black player, to work harder.

Black students also had strong support from black staff at the school, including the president’s assistant who volunteered to drive Ward across town to southwest Atlanta. Willie Harris, the school’s black athletic trainer and bus driver, was a strong supporter of Wade and other black athletes at the school.

Years later, Purdy interviewed some of the school’s first black students, documenting how they went on to attend top-notch universities and build successful careers.

Dawn Clark enrolled at St. Andrews University and later earned an MBA from the University of Tennessee. McBay, Wade and Ward enrolled at Stanford University, Morehouse College, and Princeton University, respectively.

McBay later earned his medical degree from the University of California, Los Angeles and trained in emergency medicine nearby at King/Drew Medical Center. Ward earned a doctoral degree at Stanford and taught at the University of Oklahoma before launching a long career at the National Science Foundation.

Although she was not interviewed for the book, another early graduate, Lisa Michelle Borders, would attend Duke University and eventually become vice president of global affairs at Coca-Cola. Borders also was president of the Women’s National Basketball Association and of the Atlanta City Council.

“The first black students graduated from Westminster having courageously navigated the school’s racist and paradoxical school climate by excelling inside and outside the classroom,” Purdy concludes. “These students relied on their own educational experiences in mostly segregated black schools, their talents inside and outside of the classrooms, their work ethic, their families and communities, and the efforts of particular white and black individuals at Westminster.”