The earth is rising in a region of Antarctica at one of the fastest rates ever recorded, as ice rapidly disappears and weight is lifted off the bedrock, according to data from a new international study.

The findings, reported in the journal Science, contain surprising and positive implications for the survival of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), which scientists had previously thought could be doomed because of the effects of climate change.

The unexpectedly fast rate of the rising earth may markedly increase the stability of the ice sheet against catastrophic collapse due to ice loss, scientists say.

Moreover, the rapid rise of the earth in this area also affects gravity measurements, which implies that up to 10 percent more ice has disappeared in this part of Antarctica than previously assumed.

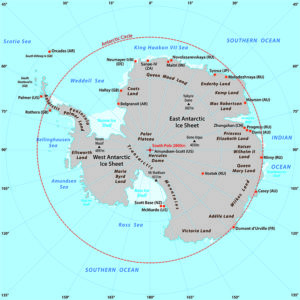

Douglas Wiens, the Robert S. Brookings Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, is part of the study team led by scientists at The Ohio State University. The researchers used a series of six GPS stations (part of the POLENET-ANET array, which Washington University helped deploy) attached to bedrock around the Amundsen Sea Embayment to measure its rise in response to thinning ice.

The uplift rate was measured at up to 41 millimeters (1.6 inches) a year.

In contrast, places like Iceland and Alaska, which are considered to exemplify rapid uplift rates, generally are measured rising 20 to 30 millimeters a year.

“The rate of uplift we found is unusual and very surprising. It’s a game changer,” said Terry Wilson, one of the leaders of the study and a professor emeritus of earth sciences at Ohio State.

And it is only going to get faster. The researchers estimate that in 100 years, uplift rates at the GPS sites will be 2.5 to 3.5 times more rapid than currently observed.

Imaging below the earth

For its role in the project, Washington University imaged the earth several hundred miles below the study area using seismographs deployed at some of the same locations as the GPS receivers.

“Our seismic images reveal that the upper mantle below the rapidly uplifting GPS sites is unusually hot and fluid, or low viscosity,” Wiens said.

“This is in agreement with the high uplift of the GPS measurements,” Wiens said. “It means that the mantle flows very quickly as the weight of the ice sheet decreases, rapidly uplifting the land surface and possibly stabilizing the ice sheet.”

“These results provide an important contribution to our understanding of the dynamics of the Earth’s bedrock, along with the thinning of ice in Antarctica. The large amount of water stored in Antarctica has implications for the whole planet,” said lead study author Valentina R. Barletta, who started this work at Ohio State and is a postdoctoral researcher at the National Space Institute (DTU Space) at the Technical University of Denmark.

“The new findings raise the need to improve ice models to get a more precise picture of what will happen in the future,” she said.

A matter of time

While modeling studies have shown that bedrock uplift could theoretically protect WAIS from collapse, it was believed that the process would take too long to have practical effects.

“We previously thought uplift would occur over thousands of years at a very slow rate, not enough to have a stabilizing effect on the ice sheet. Our results suggest the stabilizing effect may only take decades,” Wilson said.

The biggest practical effect of the uplift may be a rare bit of good news for what is happening in this part of Antarctica as a result of climate change, Wilson said.

The WAIS plays a key role in sea level rise. Estimates suggest this ice sheet alone accounts for one-fourth of global sea level rise that can be attributed to disappearing snow and ice.

Some scientists suggest that the WAIS may have passed a tipping point in which ice loss can no longer be stopped, which could be catastrophic, Wilson said. The glaciers there contain enough water to raise global sea levels up to 4 feet.

The problem is that much of this area of Antarctica is below sea level. Relatively warm ocean water has flowed in underneath the bottom of the ice sheet, causing thinning and moving the grounding line — where the water, ice and solid earth meet — farther inland.

The process seemed unstoppable, Wilson said. “But we found feedbacks that could slow or even stop the process.”

While this study delivers some potentially good news for the Amundsen Sea Embayment, that doesn’t mean all is well in Antarctica.

“The physical geography of Antarctica is very complex. We found some potentially positive feedbacks in this area, but other areas could be different and have negative feedbacks instead,” she said. Regardless of feedbacks, models suggest that the WAIS will collapse if future global warming is large.

Read the full story in a news release by Ohio State University.