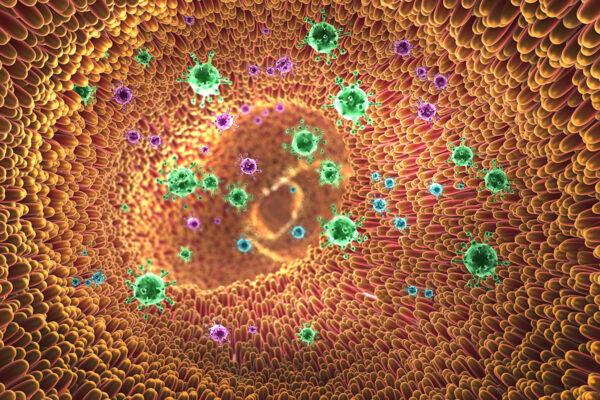

People infected with West Nile virus can show a wide range of disease. Some develop life-threatening brain infections. Others show no signs of infection at all. One reason for the different outcomes may lie in the community of microbes that populate their intestinal tracts.

A study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that mice are more susceptible to severe West Nile disease if they have recently taken antibiotics that change the makeup of their gut bacterial community.

“The immune system is activated differently if the gut does not have a healthy microbiome,” said senior author Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine. “If someone is sick with a bacterial infection, they absolutely should take antibiotics. But it is important to remember that there may be collateral effects. You might be affecting your immune response to certain viral infections.”

The study is published March 27 in Cell Reports.

West Nile virus is not unusual in its ability to cause disease ranging from mild to severe. Many viral infections cause no symptoms in the majority of people, mild to moderate disease in some, and severe disease in an unlucky few.

But why people respond so differently to the same organism has never been entirely clear. Human genetics doesn’t explain everything, and neither does the genetic makeup of the microbe itself, although both play a role.

Diamond, first author Larissa Thackray, assistant professor of medicine, and colleagues from Washington University set out to determine whether antibiotic use could help explain why some people get very sick and others do not. Antibiotics kill off members of the normal bacterial community and allow some potentially harmful ones to overgrow. Since a healthy immune system depends on a healthy gut microbiome, they reasoned, antibiotics may be hobbling the immune system, leaving the body unprepared to fight off a subsequent viral infection.

The researchers gave mice a placebo or a cocktail of four antibiotics – vancomycin, neomycin, ampicillin and metronidazole – for two weeks before infecting the mice with West Nile virus. About 80 percent of the mice that received no antibiotics survived the infection, while only 20 percent of the antibiotic-treated mice did.

Subsequent experiments showed that the mice stayed at high risk for more than a week after the antibiotic treatment ended, and just three days of antibiotic treatment was enough to raise the mice’s risk of dying from West Nile infection.

To find out whether increased susceptibility to viral infection was linked to changes in gut bacteria, the researchers tested the four antibiotics separately and in combination. Treatment with ampicillin or vancomycin alone made the mice more likely to die of West Nile, while neomycin did not. Metronidazole had no effect alone, but it amplified the effect of ampicillin or vancomycin. Further, different antibiotic treatments led to changes to the bacterial community in the gut that correlated with vulnerability to viral infection.

“Once you put a dent in a microbial community, unexpected things happen,” Thackray said. “Some groups of bacteria are depleted and different species grow out. So increased susceptibility may be due to both the loss of a normal signal that promotes good immunity and the gain of an inhibitory signal.”

The researchers tested immune cells from mice treated with antibiotics and found that they had low numbers of an important immune cell known as killer T cells. Normally, during an infection T cells that recognize the invading virus multiply to high numbers and play a critical role in controlling the infection. Mice treated with antibiotics generated fewer such T cells.

“It’s likely that antibiotic use could increase susceptibility to any virus that is controlled by T cell immunity, and that’s many of them,” Thackray said.

The weak T cell response is likely a byproduct of the changes to the bacterial populations caused by the antibiotics, not a direct effect of the drugs on the immune cells. For one thing, the mice still had trouble fending off viral infection a week or more after they stopped receiving antibiotics. For another, transferring gut bacteria from mice given antibiotics to other antibiotic-treated mice made the recipients even more vulnerable to viral infection, suggesting that something in the bacteria was undermining the mice’s immune response.

The study was done in mice and needs to be confirmed in people, whose microbiota normally contains a different collection of bacteria than mice’s, the researchers said. Still, the findings suggest that taking antibiotics unnecessarily may be unwise.

“There’s a number of people who get sick, some more than others, for reasons we don’t understand,” said Diamond, who is also a professor of molecular microbiology, and of pathology and immunology. “If your immune system doesn’t get activated because your microbiome is perturbed by antibiotics or anything else — diet, other infections, underlying medical conditions — you may be at higher risk of severe viral disease.”