Trauma is the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 46. In the U.S., there are about 30,000 preventable deaths each year in patients with severe bleeding from trauma.

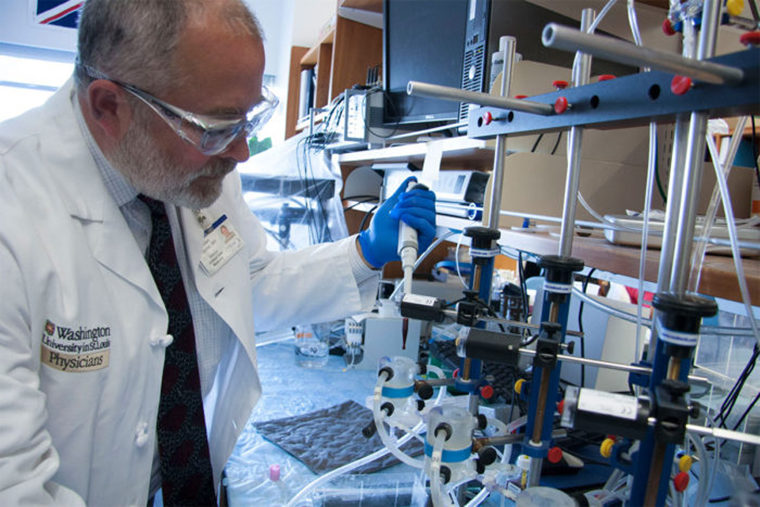

In an effort to stem the number of fatalities, a research team led by Allan Doctor, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, is working to develop artificial red blood cells to serve as a blood substitute and a bridging therapy that might keep injured people alive until they can get to a hospital. His progress will be aided by two new grants totaling $5 million.

The complementary grants — one from the U.S. Department of Defense and the other from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — will fund critical studies to further develop the artificial red cells. If successful, such a blood substitute could reduce trauma deaths in situations where blood supply is limited — for example, in military combat, civilian mass casualty incidents or in rural areas.

“There is a substantial need for an effective and portable blood substitute,” said Doctor, also an associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics.

Doctor and his team are developing a freeze-dried, powdered blood substitute, called ErythoMer, comprised of nano-scale synthetic red blood cells that can deliver oxygen throughout the body. The artificial red cells contain purified human hemoglobin, the blood protein that transports oxygen. The hemoglobin is encapsulated in a polymer shell that regulates oxygen capture and release and prevents adverse interactions between hemoglobin and vasoactive molecules in blood plasma, which might otherwise lead to vessel narrowing and critically limited blood flow.

Unlike fresh blood that becomes unusable after 42 days if refrigerated and only a few hours if unrefrigerated, freeze-dried ErythoMer can be stored at ambient temperatures for extended periods. Additionally, earlier studies suggest it could be given to people regardless of their blood type.

“ErythroMer can be stocked on an ambulance shelf, carried in a backpack in austere environments such as a battlefield or a remote village, and it easily can be stored in depot fashion in anticipation of civilian disasters,” said Doctor, who also treats critical care patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “ErythroMer then can be reconstituted with water at the point of care and used as a life-saving, stopgap measure until the patient can be brought to a field hospital or medical center.”

The blood substitute has been tested successfully in mice and rats. The new funding will support further study in larger animals.

“If such studies show promise, ErythroMer could enter human trials within five to eight years,” Doctor said.

He created the synthetic, polymer-encased blood cells in partnership with Dipanjan Pan, a former School of Medicine faculty member who is now associate professor of bioengineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and Washington University researchers Greg M. Lanza, MD, PhD, the James R. Hornsby Family Professor of Biomedical Sciences; and Philip Spinella, MD, a professor of pediatrics and director of the Pediatric Critical Care Blood Research Program.

“ErythroMer has potential to be one of the most transformative developments in trauma and critical care medicine,” Spinella said. “The ability to mitigate life-threatening blood loss for patients who would not have otherwise had access to red blood cells likely will have dramatic effects on survival and overall outcomes for these patients.”