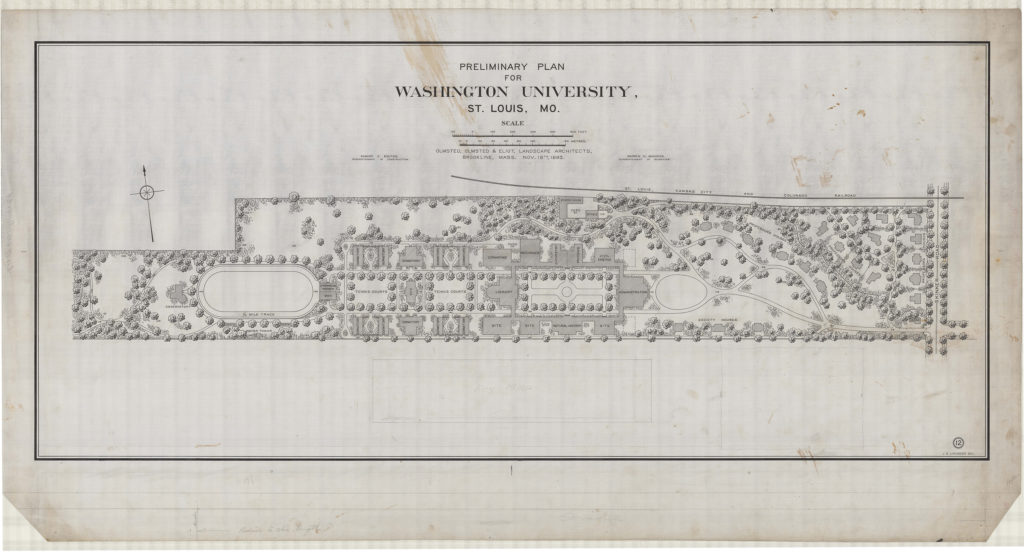

Every site possesses a spirit, or “genius,” of its own. So believed Frederick Law Olmsted, the founder of American landscape architecture. In 1895, Washington University engaged Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot, the firm led by his sons John C. and Frederick Jr., to study an undeveloped hilltop along St. Louis’ western edge. Charmed by the site’s “commanding monumental aspect,” the Olmsted brothers crafted the first plan for what is now the university’s Danforth Campus.

This spring, the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum will revisit the legacy of the Olmsted firm as part of “Transformative Visions: Washington University’s East End, Then and Now.” Occasioned by current east end construction, the exhibition includes photographs, architectural drawings, models and videos exploring the complex relationship between planning, building design, and construction that has shaped the university’s main point of entry.

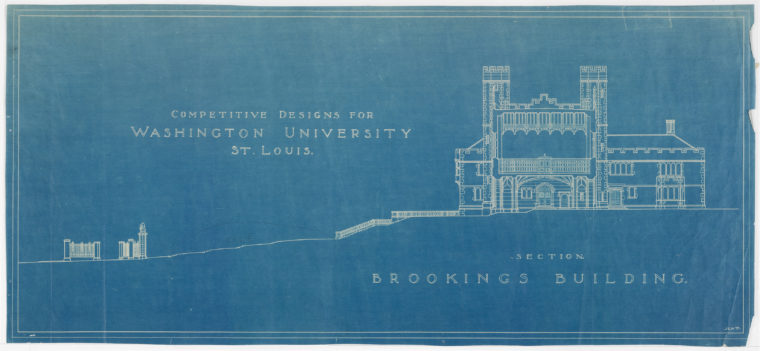

The Olmsted firm’s site plan from 1895, along with the subsequent “block plan” by Philadelphia architects Cope & Stewardson, established several key design elements. These include the strategically prominent position of Robert S. Brookings Hall, the university’s iconic administration building; the use of quadrangles and courtyards to frame outdoor space; and the large, park-like “front door” connecting the campus, visually and physically, to St. Louis’ renowned Forest Park.

Cope & Stewardson also specified the university’s dominant architecture style, Collegiate Gothic. But one of the first buildings erected east of Brookings was the Baroque, wood-framed British Royal Pavilion, created as part of the 1904 World’s Fair. A reproduction of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Orangery in London’s Kensington Gardens, the pavilion was intended as a temporary structure yet remained on site for more than two decades, providing studio and classroom space for the School of Fine Arts.

The process of establishing more permanent quarters began in 1918, when architecture professor Gabriel Ferrand developed the first dedicated east end plan. Building on Ferrand’s work — which emphasized the Beaux-Arts ideals of unity, proportional harmony, and symmetry — the St. Louis firm Jamieson & Spearl oversaw completion of William K. Bixby Hall, the British pavilion’s neoclassical replacement, in 1926, and Joseph B. Givens Hall, home to the School of Architecture, in 1932.

Like Ferrand, Jamieson & Spearl envisioned a museum connecting Bixby and Givens. But it wasn’t until 1957 that Fumihiko Maki, a young faculty member and future Pritzker Prize winner, was commissioned to design Mark C. Steinberg Hall. A groundbreaking work of 20th-century modernism, Steinberg included the first permanent exhibition space for the university’s acclaimed art collection on the Danforth Campus. Four decades later, Maki returned to design the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum building and Earl E. and Myrtle E. Walker Hall as architectural centerpieces for the newly consolidated Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts.

In 2006, the School of Engineering & Applied Science selected RMJM Hillier to develop a master plan for the northeast edge of campus. Building on principals established by Cope & Stewardson — as well as the design of Uncas A. Whitaker Hall, completed in 2003 — the RMJM Hillier plan guided construction of Stephen F. and Camilla T. Brauer Hall (2009) and Preston M. Green Hall (2011). Meanwhile, Moore Ruble Yudell and Mackey Mitchell Architects conceived the Brown School’s Thomas and Jennifer Hillman Hall (2015), which sits between Brookings and Givens, as an elegant transition between central and eastern portions of campus.

The park-like setting first envisioned by Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot served as an important precedent for today’s east end transformation, which broke ground in 2017. The plan, led by Michael Vergason Landscape Architects, encompasses Anabeth and John Weil Hall, the Gary M. Sumers Welcome Center, the Craig and Nancy Schnuck Pavilion, and an expanded Kemper Art Museum, all designed by KieranTimberlake; Henry A. and Elvira H. Jubel Hall, designed by Moore Ruble Yudell and Mackey Mitchell; and James M. McKelvey, Sr. Hall, designed by Perkins Eastman with patterhn ives, LLC.

Linking these together is Ann and Andrew Tisch Park, a welcoming green space rooted, like the Olmsted firm’s design more than a century before, in its commitment to sustainability, pedestrian movement and preserving the character of the natural surroundings.

Organizers and support

“Transformative Visions” is curated by Leslie Markle, curator for public art in the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum; James Kolker, university architect and associate vice chancellor; and Eric Mumford, the Rebecca and John Voyles Professor of Architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. Exhibition support is provided by the William T. Kemper Foundation, Elissa and Paul Cahn, and members of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum.

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

“Transformative Visions” will open at the Kemper Art Museum with a free public reception from 7 to 9 p.m. Friday, Feb. 2, and will remain on view through May 21. Related events include a gallery talk with the curators (Feb. 3) and a lecture by Mumford about the work of Fumihiko Maki, the internationally acclaimed architect of Steinberg, Kemper and Walker Halls (April 11).

The museum is located on Washington University’s Danforth Campus, near the intersection of Skinker and Forsyth Boulevards. Regular hours are 11 a.m.-5 p.m. daily except Tuesdays and University holidays. For more information, call 314-935-4523; visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu; or follow the museum on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Editor’s note: The current transformation of the east end of Washington University’s Danforth Campus affects parking and access to the Museum; see here for details. As part of that transformation, the museum will close for renovations and expansion in summer 2018. The museum will reopen in fall 2019.