Researchers have long sought ways to harness the body’s immune system to treat disease, especially cancer. Now, scientists have found that the immune system may be triggered to treat atherosclerosis and possibly other metabolic conditions, including fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes.

Studying mice, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown that a natural sugar called trehalose revs up the immune system’s cellular housekeeping abilities. These souped-up housecleaners then are able to reduce atherosclerotic plaque that has built up inside arteries. Such plaques are a hallmark of cardiovascular disease and lead to an increased risk of heart attack.

The study is published June 7 in Nature Communications.

“We are interested in enhancing the ability of these immune cells, called macrophages, to degrade cellular garbage — making them super-macrophages,” said senior author Babak Razani, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine.

Macrophages are immune cells responsible for cleaning up many types of cellular waste, including misshapen proteins, excess fat droplets and dysfunctional organelles — specialized structures within cells.

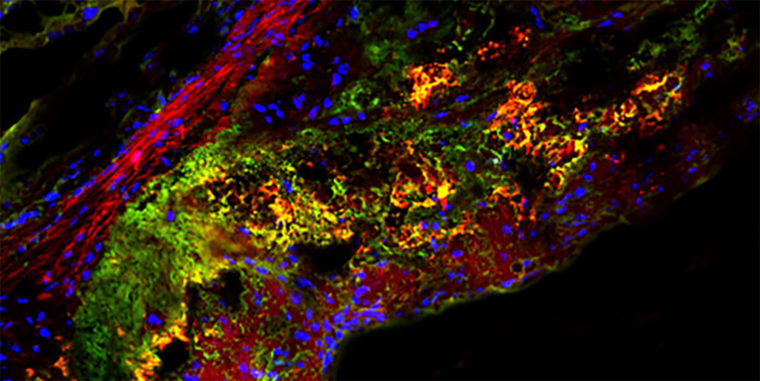

“In atherosclerosis, macrophages try to fix damage to the artery by cleaning up the area, but they get overwhelmed by the inflammatory nature of the plaques,” Razani explained. “Their housekeeping process gets gummed up. So their friends rush in to try to clean up the bigger mess and also become part of the problem. A soup starts building up — dying cells, more lipids. The plaque grows and grows.”

In the study, Razani and his colleagues showed that mice prone to atherosclerosis had reduced plaque in their arteries after being injected with trehalose. The sizes of the plaques measured in the aortic root were variable, but on average, the plaques measured 0.35 square millimeters in control mice compared with 0.25 square millimeters in the mice receiving trehalose, which translated into a roughly 30 percent decrease in plaque size. The difference was statistically significant, according to the study.

The effect disappeared when the mice were given trehalose orally or when they were injected with other types of sugar, even those with similar structures.

Found in plants and insects, trehalose is a natural sugar that consists of two glucose molecules bound together. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for human consumption and often is used as an ingredient in pharmaceuticals. Past work by many research groups has shown trehalose triggers an important cellular process called autophagy, or self-eating. But just how it boosts autophagy has been unknown.

In this study, Razani and his colleagues show that trehalose operates by activating a molecule called TFEB. Activated TFEB goes into the nucleus of macrophages and binds to DNA. That binding turns on specific genes, setting off a chain of events that results in the assembly of additional housekeeping machinery — more of the organelles that function as garbage collectors and incinerators.

“Trehalose is not just enhancing the housekeeping machinery that’s already there,” Razani said. “It’s triggering the cell to make new machinery. This results in more autophagy — the cell starts a degradation fest. Is this the only way that trehalose works to enhance autophagy by macrophages? We can’t say that for sure — we’re still testing that. But is it a predominant process? Yes.”

The researchers are continuing to study trehalose as a potential therapy for atherosclerosis, especially since it is not only safe for human consumption but is also a mild sweetener. One obstacle the scientists would like to overcome, however, is the need for injections. Trehalose likely loses its effectiveness when taken orally because of an enzyme in the digestive tract that breaks trehalose into its constituent glucose molecules. Razani said the research team is looking for ways to block that enzyme so that trehalose retains its structure, and presumably its function, when taken by mouth.