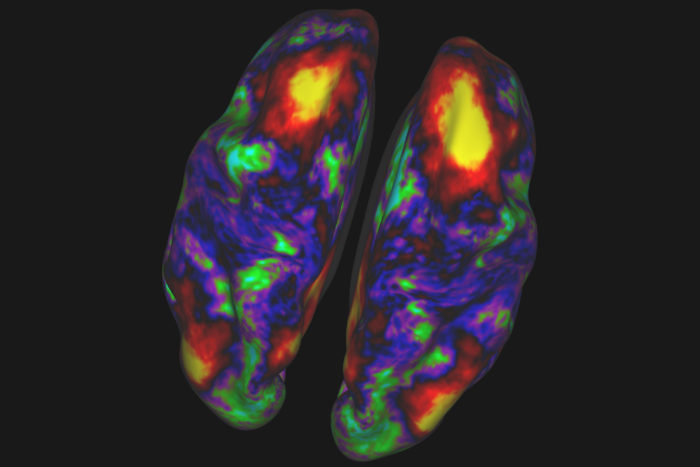

Throughout our lives, our brains are always changing. To capture that transformation, scientists will scan the brains of people from kindergarten through their later years to build maps of the brain as it develops and changes over the decades.

The endeavor, led by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis, is funded by two grants totaling $34 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The new projects are a follow-up to the Human Connectome Project, also funded by the NIH, which mapped the neural connections of young adults ages 22 to 35. That effort, co-led by Washington University investigators, is wrapping up this fall after making major contributions in regard to how we acquire, analyze and share information about the living brain.

Now, Washington University scientists have been awarded $17 million to fill in the missing gaps by scanning the brains of more than 1,300 children and young adults ages 5 to 21, and another $17 million to scan 1,200 adults ages 36 to over 100. Together, all of these will be part of the “Lifespan Human Connectome Project” that will cover almost the entire human lifespan. Many of the participants in these new studies will be scanned at two or three time points, enabling researchers to study how the brain changes in an individual subject over time.

The researchers at Washington University will be joined by teams at Harvard University/Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Minnesota, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Oxford University in the United Kingdom. Altogether, the studies will investigate what a healthy brain looks like at different stages of life, by building upon methods pioneered by the earlier Human Connectome Project.

“Right now, we still do not know what healthy aging is in the brain,” said Beau Ances, MD, PhD, a co-principal investigator on the adult grant and an associate professor of neurology at the School of Medicine. “The data obtained in this study will provide us more accurate information about what normal healthy brains look like across the lifespan. From this data we will begin to be able to tease apart healthy aging from early preclinical signs of neurological or psychiatric illnesses.”

David Van Essen, a co-principal investigator on both the child and adult grants, and the Alumni Endowed Professor of Neuroscience at the School of Medicine, said that people who study neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, already have been contacting the researchers.

“They’re anxious to get this data. Once we’ve established a baseline of healthy aging, other scientists will be better able to differentiate normal aging from changes due to disease,” Van Essen said.

Deanna Barch, a co-principal investigator on the study involving children, added, “Many of the mental and physical health conditions associated with brain structure and function that are challenging for adults often begin in childhood. However, we need to know more about how the brain ‘grows up’ in healthy children.

“Understanding how age and puberty shape and sculpt brain development in healthy children will be an invaluable tool in our search to understand how and why brain maturation is different in children who develop illnesses early in life, such as autism, or even later in life,” continued Barch, who is head of the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences in Arts & Sciences and the Gregory Couch Professor of Psychiatry in the School of Medicine.

Each study participant will spend a total of about two hours in an MRI scanner, broken up into two sessions. The data will allow researchers to examine many different features of the brain, especially those in the cerebral cortex, which is involved in memory, attention, perception, awareness, thought, language and consciousness. These features will include how different parts of the brain work together, how they are connected or “wired” together, and how they are activated when people are doing tasks.

In addition, in the children, the study will examine how the brain changes with puberty as well as with age, and how these changes are similar or different for boys and girls.

Participants will perform simple tasks during their scans, such as making decisions that could lead to rewards, trying to remember pictures or objects, or pressing buttons, which will help pinpoint the areas of the brain involved in such tasks and how they work together.

The project is designed to draw from a racially and ethnically diverse population. Between the different study sites, the researchers expect to be able to recruit participants that reflect the demographics of the United States.

The researchers also will collect information about obesity, smoking status, diet, stress, sleep patterns and other factors. Blood will be drawn from each participant to analyze hormone levels and markers of inflammation and metabolism. A portion of the blood will be banked for future research efforts.

Like the Human Connectome Project, a major goal of the new project is to share data with the rest of the scientific community.

The researchers plan to release data publicly at least every six months and more frequently if they can manage it. The brain scans will be available both raw – “exactly as we get them off the scanner,” according to Van Essen, as well as cleaned up and aligned for easier analysis. Along with the scans, researchers will have access to anonymized demographic and health information about each participant. The team also will be releasing the algorithms they use to process and analyze the data.

“We’re kind of like explorers,” Ances said. “Like Columbus or Magellan, we’re making the maps that others can use to understand the effects of aging on brain structure and function.”