Dear, deer, deare, deere.

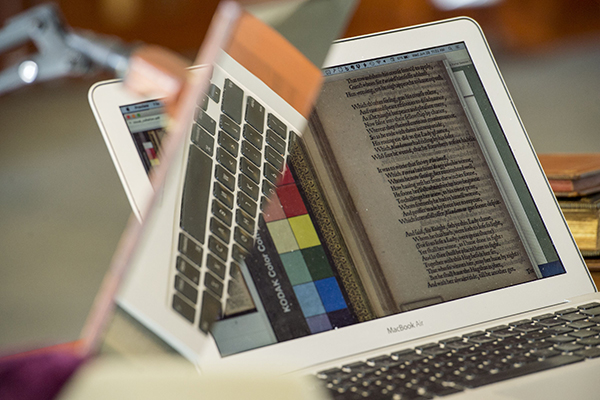

Digitizing modern texts is easy. Scan a page and optical character recognition software does the rest. But digitizing texts from the early days of printing? That turns out to be surprisingly difficult.

“Machines are good at fixing errors,” said Joe Loewenstein, director of the Humanities Digital Workshop in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “Your phone can tell you when a word is misspelled. But when spelling isn’t stable — when there are many ways to spell the same word — machine correction doesn’t do you much good.”

Since 1999, the Text Creation Partnership (TCP) — a cooperative venture jointly funded by 150 libraries worldwide — has transcribed more than 60 percent of the output of the English press between 1475 and 1700. It is a remarkable achievement, with the potential to revolutionize how scholars understand early modern literature, politics, religion, science and social history.

Yet amidst these 60,000 texts and 1.65 billion words, there remain substantial errors.

Correcting the record

Over the last three years, students and faculty at Washington University and Northwestern University have led a pilot program seeking to reduce error rates in a subset of early modern drama.

“Many TCP transcriptions are based on scans of microfilms of particular copies located at particular institutions,” Loewenstein said. Each link in that chain increases the likelihood of data degradation. In addition, in the early modern period, paper was expensive.

“Corrections get made while things are still being printed,” he said. “When you look at a page, you may be looking at a corrected or an uncorrected version.”

The group began by flagging transcription defects in a subset of 500 plays by Shakespeare’s contemporaries. Students then traveled to libraries housing physical copies of the works in question; compared the original texts to data in the TCP’s Early English Books Online archive; and logged their corrections. The error rate dropped from 14 to 1.1 per 10,000 words.

“The results were striking,” Loewenstein said. “Basically we showed that a small group of smart undergraduates could make a huge dent.”

The Early Modern Lab

Those corrected transcriptions recently became the backbone for the new Digital Anthology of Early Modern English Drama, launched this spring by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, a $200,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation is funding creation of the new Early Modern Lab, which will address two additional sections of the TCP corpus — Anglo-Irish materials and texts relating to the English Civil War — as well as the output of the American press between 1750 and 1800.

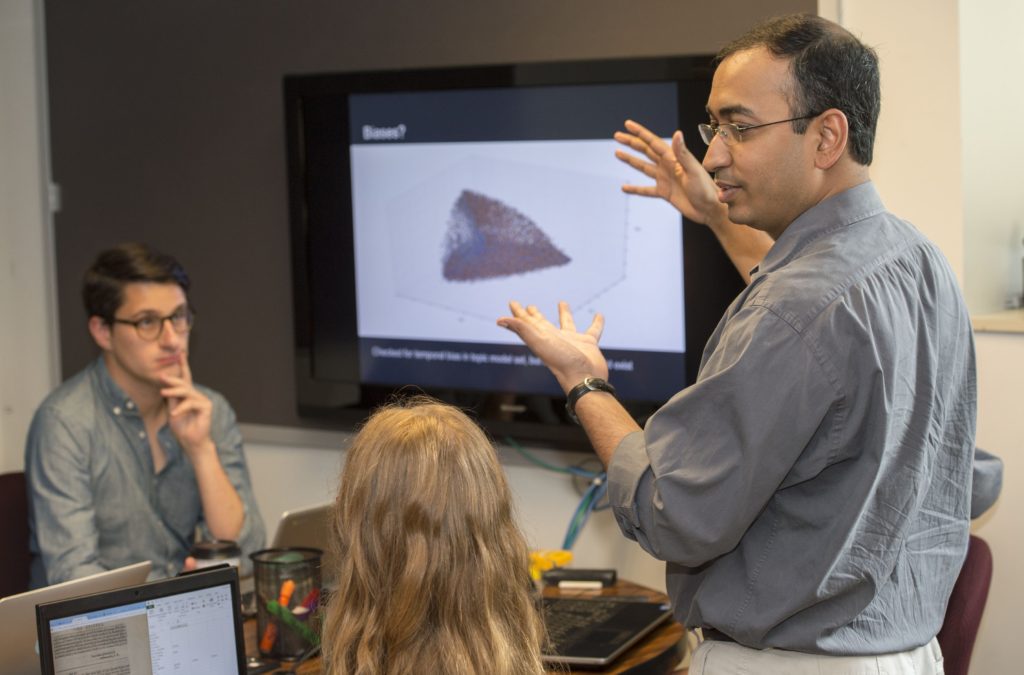

Loewenstein serves as one of lab’s lead investigators, along with Martin Mueller of Northwestern and Tracy Bergstrom of the University of Notre Dame. Rounding out the Washington University team are Anupam Basu, assistant professor of English in Arts & Sciences; Douglas Knox and Stephen Pentecost of the Arts & Sciences Computing Center; Cindy Traub (PhD ’06), a data specialist with Olin Library; and recent graduates Kate Needham and Keegan Hughes.

Though many corrections can be crowd-sourced, the group’s primarily challenge is to develop ways of tracking and synthesizing individual contributions. “Digital scholarship allows you to harness a lot of energy and good will, but there’s still an editorial function,” Loewenstein said. “How do you incorporate all that work into some sort of official stream? It’s a problem across all branches of knowledge.

“In the next phase, we’ll try some machine correction,” Loewenstein said. “In many cases, the errors are things that a well trained algorithm can fix.” But he also strikes a note of caution, particularly about errors that exist in the original texts. “It’s easy enough to make the right guess, but its very difficult to make the accurate wrong guess.”

The group also is building a prototype “recommendation engine,” based on Basu’s analysis of word clusters, formatting conventions and other subtle patterns in the TCP data.

“One of the most interesting things that Anupam discovered is that if you give the machine just the formatting information from five comedies and ask it to find five more similar texts, what comes back are other comedies, not tragedies,” Loewenstein said. “The algorithm detects patterns that lie beneath the notice of a skilled human reader.”

The hope is that such linguistic and structural breakdowns will help scholars uncover hidden connections between seemingly disparate texts.

“Library of Congress classifications separate plays from prose fiction, sermons from scientific treatises,” Loewenstein said. “We want to capture how differently classified texts cohere, across those classifications.”

Read like an expert

Almost paradoxically, this sort of broad statistical work can showcase qualities that make individual writers unique. Loewenstein gives the example of Edmund Spenser, the 16th century poet whose idiosyncratic vocabulary often drew on medieval forms.

“When a novice reads Spenser, its hard to get at what’s really weird about him,” said Loewenstein, who also serves as principal investigator for The Spenser Archive, the digital component of Oxford University Press’s forthcoming “Collected Works of Edmund Spenser.”

“It’s hard to tell what would have looked familiar and what would have looked strange to a 16th century reader,” he said. “It all just looks old.

“But now, thanks to Anupam’s work, we’re able to color-code the language. We can say, ‘This is strange, and this is strange, but this is perfectly normal.’ Now the modern reader is equipped to read like a 16th-century expert.

“Suddenly, you can see the fingerprints of the author,” he said. “It’s a beautiful thing.”