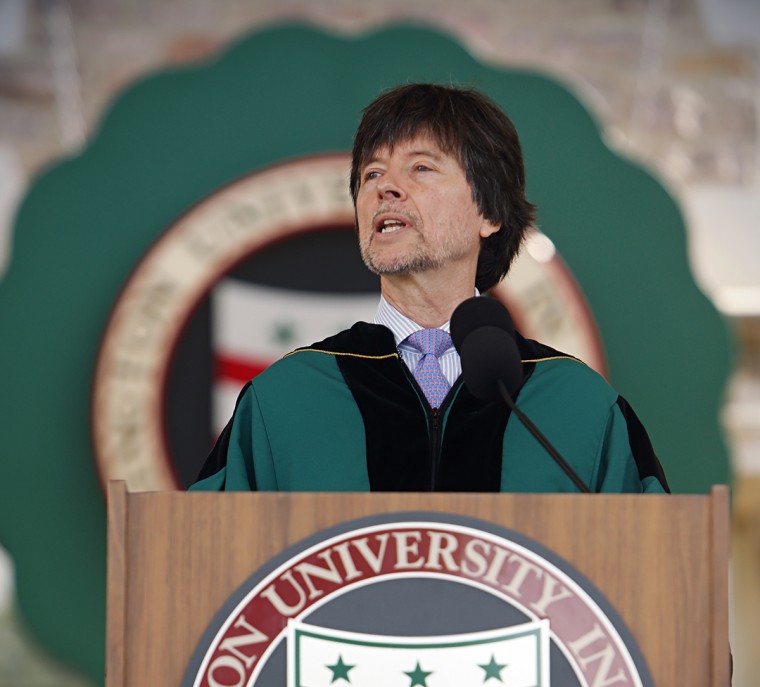

Chancellor Wrighton, members of the Board of Trustees and the Administration, distinguished faculty, Class of 1965, hard-working staff, my fellow honorees, proud and relieved parents, calm and serene grandparents, distracted but secretly pleased siblings, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, graduating students, good morning. I am deeply honored that you have asked me here to say a few words at this momentous occasion, that you might find what I have to say worthy of your attention on so important a day at this remarkable institution.

It had been my intention this morning to parcel out some good advice at the end of these remarks — the “goodness” of that being of course subjective in the extreme — but then I realized that this is the land of Mark Twain, and I came to the conclusion that any commentary today ought to be framed in the sublime shadow of this quote of his: “It’s not that the world is full of fools, it’s just that lightening isn’t distributed right.” More on Mr. Twain later.

I am in the business of history. It is my job to try to discern some patterns and themes from the past to help us interpret our dizzyingly confusing and sometimes dismaying present. Without a knowledge of that past, how can we possibly know where we are and, most important, where we are going? Over the years I’ve come to understand an important fact, I think: that we are not condemned to repeat, as the cliché goes and we are fond of quoting, what we don’t remember. That’s a clever, even poetic phrase, but not even close to the truth. Nor are there cycles of history, as the academic community periodically promotes. The Bible, Ecclesiastes to be specific, got it right, I think: “What has been will be again. What has been done will be done again. There is nothing new under the sun.”

What that means is that human nature never changes. Or almost never changes. We have continually superimposed our complex and contradictory nature over the random course of human events. All of our inherent strengths and weaknesses, our greed and generosity, our puritanism and our prurience parade before our eyes, generation after generation after generation. This often gives us the impression that history repeats itself. It doesn’t. It just rhymes, Mark Twain is supposed to have said…but he didn’t (more on Mr. Twain later.)

Over the many years of practicing, I have come to the realization that history is not a fixed thing, a collection of precise dates, facts and events (even cogent commencement quotes) that add up to a quantifiable, certain, confidently known, truth. It is a mysterious and malleable thing. And each generation rediscovers and re-examines that part of its past that gives its present, and most important, its future new meaning, new possibilities and new power.

Listen. For most of the forty years I’ve been making historical documentaries, I have been haunted and inspired by a handful of sentences from an extraordinary speech I came across early in my professional life by a neighbor of yours just up the road in Springfield, Illinois. In January of 1838, shortly before his 29th birthday, a tall, thin lawyer, prone to bouts of debilitating depression, addressed the Young Men’s Lyceum. The topic that day was national security. “At what point shall we expect the approach of danger?” he asked his audience. “…Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant to step the Earth and crush us at a blow?” Then he answered his own question: “Never. All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa … could not by force take a drink from the Ohio [River] or make a track on the Blue Ridge in a trial of a thousand years … If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.” It is a stunning, remarkable statement.

That young man was, of course, Abraham Lincoln, and he would go on to preside over the closest this country has ever come to near national suicide, our Civil War — fought over the meaning of freedom in America. And yet embedded in his extraordinary, disturbing and prescient words is a fundamental optimism that implicitly acknowledges the geographical force-field two mighty oceans and two relatively benign neighbors north and south have provided for us since the British burned the White House in the War of 1812.

We have counted on Abraham Lincoln for more than a century and a half to get it right when the undertow in the tide of those human events has threatened to overwhelm and capsize us. We always come back to him for the kind of sustaining vision of why we Americans still agree to cohere, why unlike any other country on earth, we are still stitched together by words and, most important, their dangerous progeny, ideas. We return to him for a sense of unity, conscience and national purpose. To escape what the late historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., said is our problem today: “too much pluribus, not enough unum.”

It seems to me that he gave our fragile experiment a conscious shock that enabled it to outgrow the monumental hypocrisy of slavery inherited at our founding and permitted us all, slave owner as well as slave, to have literally, as he put it at Gettysburg, “a new birth of freedom.”

Lincoln’s Springfield speech also suggests what is so great and so good about the people who inhabit this lucky and exquisite country of ours (that’s the world you now inherit): our work ethic, our restlessness, our innovation and our improvisation, our communities and our institutions of higher learning, our suspicion of power; the fact that we seem resolutely dedicated to parsing the meaning between individual and collective freedom; that we are dedicated to understanding what Thomas Jefferson really meant when he wrote that inscrutable phrase “the pursuit of Happiness.”

But the isolation of those two mighty oceans has also helped to incubate habits and patterns less beneficial to us: our devotion to money and guns; our certainty — about everything; our stubborn insistence on our own exceptionalism, blinding us to that which needs repair, our preoccupation with always making the other wrong, at an individual as well as global level.

And then there is the issue of race, which was foremost on the mind of Lincoln back in 1838. It is still here with us today. The jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis told me that healing this question of race was what “the kingdom needed in order to be well.” Before the enormous strides in equality achieved in statutes and laws in the 150 years since the Civil War that Lincoln correctly predicted would come are in danger of being undone by our still imperfect human nature and by politicians who now insist on a hypocritical color-blindness — after four centuries of discrimination. That discrimination now takes on new, sometimes subtler, less obvious but still malevolent forms today. The chains of slavery have been broken, thank God, and so too has the feudal dependence of sharecroppers as the vengeful Jim Crow era recedes (sort of) into the distant past. But now in places like — but not limited to — your other neighbors a few miles as the crow flies from here in Ferguson, we see the ghastly remnants of our great shame emerging still, the shame Lincoln thought would lead to national suicide, our inability to see beyond the color of someone’s skin. It has been with us since our founding.

When Thomas Jefferson wrote that immortal second sentence of the Declaration that begins, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…,” he owned more than a hundred human beings. He never saw the contradiction, never saw the hypocrisy, and more important never saw fit in his lifetime to free any one of those human beings, ensuring as we went forward that the young United States — born with such glorious promise — would be bedeviled by race, that it would take a bloody, bloody Civil War to even begin to redress the imbalance.

But the shame continues: prison populations exploding with young black men, young black men killed almost weekly by policemen, whole communities of color burdened by corrupt municipalities that resemble more the predatory company store of a supposedly bygone era than a responsible local government. Our cities and towns and suburbs cannot become modern plantations.

It is unconscionable, as you emerge from this privileged sanctuary, that a few miles from here — and nearly everywhere else in America: Baltimore, New York City, North Charleston, Cleveland, Oklahoma, Sanford, Florida, nearly everywhere else — we are still playing out, sadly, an utterly American story, that the same stultifying conditions and sentiments that brought on our Civil War are still on such vivid and unpleasant display. Today, today. There’s nothing new under the sun.

Many years after our Civil War, in 1883, Mark Twain took up writing in earnest a novel he had started and abandoned several times over the last half-dozen years. It would be a very different kind of story from his celebrated Tom Sawyer book, told this time in the plain language of his Missouri boyhood — and it would be his masterpiece.

Set near here, before the Civil War and emancipation, ‘the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ is the story of two runaways — a white boy, Tom Sawyer’s old friend Huck, fleeing civilization, and a black man, Jim, who is running away from slavery. They escape together on a raft going down the Mississippi River.

The novel reaches its moral climax when Huck is faced with a terrible choice. He believes he has committed a grievous sin in helping Jim escape, and he finally writes out a letter, telling Jim’s owner where her runaway property can be found. Huck feels good about doing this at first, he says, and marvels at “how close I came to being lost and going to hell.”

But then he hesitates, thinking about how kind Jim has been to him during their adventure. “…Somehow,” Huck says, “I couldn’t seem to strike no place to harden me against him, but only the other kind. I’d see him standing my watch on top of his’n, ‘stead of calling me, so I could go on sleeping; and see how glad he was when I come back out of the fog;…and such like times; and would always call me honey…and do everything he could think of for me, and how good he always was…”

Then, Huck remembers the letter he has written. “I took it up, and held it in my hand,” he says. “I was a-trembling because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself: ‘All right then, I’ll go to hell’ — and tore it up.”

That may be the finest moment in all of American literature. Ernest Hemingway thought all of American literature began at that moment.

Twain, himself, writing after the Civil War and after the collapse of Reconstruction, a misunderstood period devoted to trying to enforce civil rights, was actually expressing his profound disappointment that racial differences still persisted in America, that racism still festered in this favored land, founded as it was on the most noble principle yet advanced by humankind — that all men are created equal. That civil war had not cleansed our original sin, a sin we continue to confront today, daily, in this supposedly enlightened “post-racial” time.

It is into this disorienting and sometimes disappointing world that you now plummet, I’m afraid, unprotected from the shelter of family and school. You have fresh prospects and real dreams and I wish each and every one of you the very best. But I am drafting you now into a new Union Army that must be committed to preserving the values, the sense of humor, the sense of cohesion that have long been a part of our American nature, too. You have no choice, you’ve been called up, and it is your difficult, but great and challenging responsibility to help change things and set us right again.

Let me apologize in advance to you. We broke it, but you’ve got to fix it. You’re joining a movement that must be dedicated above all else — career and personal advancement — to the preservation of this country’s most enduring ideals. You have to learn, and then re-teach the rest of us that equality — real equality — is the hallmark and birthright of ALL Americans. Thankfully, you will become a vanguard against a new separatism that seems to have infected our ranks, a vanguard against those forces that, in the name of our great democracy, have managed to diminish it. Then, you can change human nature just a bit, to appeal, as Lincoln also implored us, to appeal to “the better angels of our nature.” That’s the objective. I know you can do it.

Ok. I’m rounding third.

Let me speak directly to the graduating class. (Watch out. Here comes the advice.)

Remember: Black lives matter. All lives matter.

Reject fundamentalism wherever it raises its ugly head. It’s not civilized. Choose to live in the Bedford Falls of “It’s a Wonderful Life,” not its oppressive opposite, Pottersville.

Do not descend too deeply into specialism. Educate all your parts. You will be healthier.

Replace cynicism with its old-fashioned antidote, skepticism.

Don’t confuse monetary success with excellence. The poet Robert Penn Warren once warned me that “careerism is death.”

Try not to make the other wrong.

Be curious, not cool.

Remember, insecurity makes liars of us all.

Listen to jazz. A lot. It is our music.

Read. The book is still the greatest manmade machine of all — not the car, not the TV, not the computer or the smartphone.

Do not allow our social media to segregate us into ever smaller tribes and clans, fiercely and sometimes appropriately loyal to our group, but also capable of metastasizing into profound distrust of the other.

Serve your country. By all means serve your country. But insist that we fight the right wars. Governments always forget that.

Convince your government that the real threat, as Lincoln knew, comes from within. Governments always forget that, too. Do not let your government outsource honesty, transparency or candor. Do not let your government outsource democracy.

Vote. Elect good leaders. When he was nominated in 1936, Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, “Better the occasional faults of a government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.” We all deserve the former. Insist on it.

Insist that we support science and the arts, especially the arts. They have nothing to do with the actual defense of the country — they just make the country worth defending.

Be about the “unum,” not the “pluribus.”

Do not lose your enthusiasm. In its Greek etymology, the word enthusiasm means simply, “God in us.”

And even though lightning still isn’t distributed right, try not to be a fool. It just gets Mark Twain riled up.

And if you ever find yourself in Huck’s spot, if you’ve “got to decide betwixt two things,” do the right thing. Don’t forget to tear up the letter. He didn’t go to hell — and you won’t either.

So we come to an end of something today—and for you also a very special beginning. God speed to you all.

Ken Burns

Walpole, New Hampshire