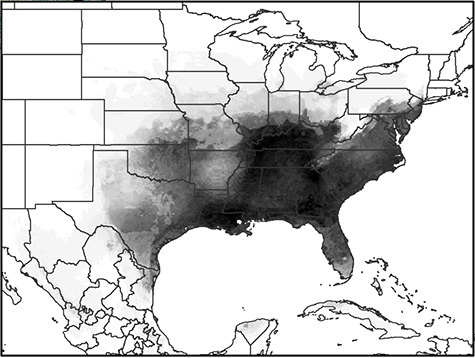

The Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), which is native to Southeast Asia, was spotted in Houston in 1985. By 1986 it had reached St. Louis and Jacksonville, Fla. Today it can be found in all of the southern states and as far north as Maine.

An aggressive daytime biter, Ae. albopictus has an affinity for humans and is also a vector for human disease, said Kim Medley, PhD, interim director of the Tyson Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis.

The mosquito arrived in the U.S. in a shipment of used tires from Japan. Ae. albopictus lays eggs that can survive even if any water evaporates, so they’re very easy to transport, said Medley. “It’s widely accepted that global trade and travel have led to many species introductions,” she said.

“But how introduced species spread and adapt to novel conditions after introduction is less well understood,” she said.

To reconstruct what happened, Medley and her colleagues at the University of Central Florida turned to the new discipline of landscape genetics. Correlating genetic patterns with landscape patterns, they concluded that the mosquito had traveled by human-aided “jump” dispersal followed by slower regional spread.

The jumps occurred when mosquitoes hitched a ride in cars or trucks, traveling in style up major highways.

Their study, published in the Oct. 27 online edition of Molecular Ecology, is one of only a handful of landscape genetics studies to track an invasive species and the first to detect hitchhiking.

Medley’s concern is not that gardeners will be driven indoors but rather that human-aided dispersal will accelerate the adaptation of the mosquitoes and the viruses they can carry to their new surroundings and to one another.

So far this year the state of Florida has reported 11 cases of locally transmitted chickungunya, a disease original to Africa that wasn’t seen in the Americas until 2013.

“The movement of invasive species by human-aided transport can have far reaching consequences,” Medley said.

A deft piece of deduction

Looking at a map of the current range of Ae. albopictus in the U.S., it is impossible to know how the mosquito spread from its point of introduction, although it could hardly have been by wing power alone, because an adult flies less than a kilometer in its lifetime.

“Even Darwin, in the 1800s, was interested in how species travel from point A to point B,” said Medley. “But measuring dispersal rates by hand is nearly impossible,” she said. “I’ve tried it. You can dust mosquitoes and release them and then try to recapture them, but capturing enough of the releases to reach any solid conclusion is really difficult.”

So to figure out how Ae. albopictus spread from the tire pile in Houston, the scientists used a technique that relies on high-tech tools such as genotyping and GIS. First introduced by French scientists in 2003, landscape genetics provides a way to rigorously test competing hypotheses for dispersal.

As a first step they had to establish the genetic structure of the U.S. Ae. albopictus population. A container mosquito, Ae. albopictus lays its eggs just above the waterline in old tires, flower pot saucers, water bowls, bird baths — and cemetery flower vases.

To sample the mosquito population, the scientists collected larvae from abandoned flower vases in cemeteries both on the edge and within the core of the mosquitoes’ U.S. range in both rural and urban areas.

“The green cylinders with the spike on the bottom are the best for collecting immature stages of mosquitoes,” Medley said.

The immature mosquitoes were raised to adults in the laboratory so the species could be accurately identified (there are 174 recognized species in the U.S.) and then the DNA was extracted from clipped legs and typed at nine different microsatellite locations.

The scientists then compared the genetic structure of the mosquito population to that predicted by 52 different models of mosquito dispersal that variously took into consideration habitat and highways.

It turned out that gene flow over long distances was correlated with highways and bodies of water. People had carried mosquitoes from the core of their range to its edge along highways, likely by semi-trailers or in cars. Wetlands and lakes were important, not because they are breeding sites, but because they tend to occur in areas where frequent rainfall refills artificial containers and supports mosquito growth.

The scientists also looked more closely at what was happening at the range edge. Because Ae. albopictus lays eggs in treeholes and is often found resting at forest edges, they expected forests at the northern edge of the mosquitoes’ range to act as natural corridors for dispersal.

It turned out forests were barriers rather than corridors, perhaps because Ae. albopictus had not been able to displace the native treehole mosquito, Ae. triseriatus.

The forest finding is an interesting example of the ability of landscape genetics to test assumptions, Medley said.

Why mosquito road trips matter

Understanding mosquito dispersal is important because the mosquito’s genes go where it goes. Human-aided gene flow between mosquito populations can give a species the smorgasbord of genetic options it needs to rapidly adapt to novel conditions, Medley said.

Ae. albopictus has already spread further north in the U.S. than expected, given its limited cold hardiness in its native range. Under selection pressure at the edge of their range, the mosquitoes might be producing eggs that respond to shortening days and the onset of winter by going into a state of dormancy, Medley said.

Dispersal also upsets the balance between the mosquito, its competitors, hosts and pathogens, raising the possibility that exotic mosquito-borne viruses will be able to take advantage of the newly cosmopolitan vector to move into the U.S.

The history of introduced Ae. albopictus and disease is not encouraging, Medley said, describing what happened when Ae. albopictus reached India and the Indian Ocean. The opportunistic virus that took advantage of the spread in this case was chickungunya.

Chickungunya, a viral infection characterized by spiking fever and severe joint pain, was first described in Africa in 1955, where it was spread by Ae. aegypti, the dominant mosquito there.

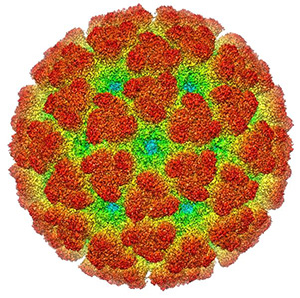

(Credit: The Electron Microscopy Data Bank )

The virus spread out of Africa to islands in the Indian Ocean, reaching the island of Réunion, in 2005. Ae. aegypti was absent or present in low numbers on Réunion, and Ae. albopictus was the dominant mosquito. The next year there were 265,000 clinical cases of chickungunya in Réunion and 237 deaths (out of a population of 770,000).

Research at the Pasteur Institute in Paris showed strains of the virus circulating in Réunion had a genetic mutation that made it easier for the virus to infect Ae. albopictus. That didn’t prove Ae. albopictus was the vector for the epidemic, but the timing strongly suggested a connection.

Also in that year, the virus was introduced into India from East Africa where it underwent the same mutation as in Réunion. This rare duplicate mutation, called an evolutionary convergence, is usually a sign of strong selection pressure, Medley said.

Conditions in the U.S. are ripe for a similar event. Both Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti are container mosquitoes, but Ae. albopictus larvae will out-compete anything in an artificial container except predatory larvae, Medley said. So as Ae. albopictus has dispersed, it has pushed out Ae. aegypti.

It is now the dominant mosquito across Florida, Medley says, where local mosquitoes have begun to vector chickungunya and Ae. albopictus is a likely suspect.

What to do?

Ae. albopictus is now well established in the U.S., so what bearing do the findings have on what we do now? Medley suggests that they should inform mosquito control efforts, particularly at the range edge where the population is fragmented and sub-populations blink in and out naturally and as a result of local eradication.

“If we eliminate a local population but leave dispersal routes open, we’re just going to have re-introductions,” she said.

“But,” she said, “my broader concern is the effect of human-aided dispersal on evolution, both the adaptation of the mosquito to northern climates and its co-evolution with chikungunya. By stopping human-aided dispersal of the mosquitoes, we might be able to prevent the further spread of the mosquitoes and the diseases they vector.”

To shut down the dispersal routes, however, we’d have to take the risk more seriously than we now do.

After all, one of the containers Ae. albopictus favors are those small pots of “lucky bamboo” sold on Amazon and eBay, and at Target, Home Depot, Walmart, Walgreens and many other retail outlets.