At St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, a section of the dome called the Whispering Gallery makes a whisper audible from the other side of the dome as a result of the way sound waves travel around the curved surface. Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have used the same phenomenon to build an optical device that may lead to new and more powerful computers that run faster and cooler.

Lan Yang, PhD, associate professor of electrical and systems engineering, and her collaborators have developed an essential component of these new computers that would run on light. Their work brings predictions from recently formulated theoretical physics into real world applications.

The results of their research appear April 6 in Nature Physics.

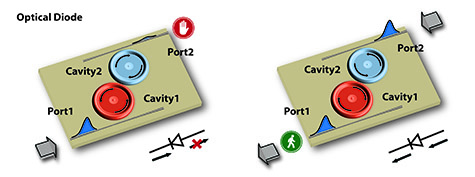

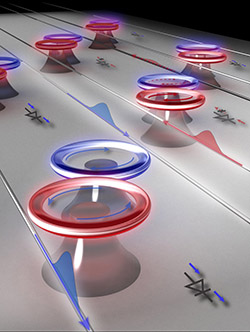

Yang’s group has created an optical diode by coupling tiny doughnut shaped optical resonators — one with gain and the other with loss — on a silicon chip. “This diode is capable of completely eliminating light transmission in one direction and greatly enhancing light transmission in the other nonreciprocal light transmission,” says Bo Peng, a graduate student in Yang’s group and the paper’s lead author.

An electrical diode prevents electricity from backflow along a wire providing protection to crucial parts of an electronic circuit or processor; an optical diode does the same thing with light.

“We believe that our discovery will benefit many other fields involving electronics, acoustics, plasmonics and meta-materials,” Yang says. “Coupling of so-called loss and gain devices using PT (parity-time)-symmetry could enable such advances as cloaking devices, stronger lasers that need less input power, and perhaps detectors that could ‘see’ a single atom.”

The principle of PT-symmetry is based upon mathematical theories advanced by Carl M. Bender, PhD, the Wilfred R. and Ann Lee Konneker Distinguished Professor of Physics in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.

Simply put, when a “lossy” system is coupled with a “gain” system such that loss of energy exactly equals gain at an equilibrium point, a “phase transition” occurs.

Applying the principles of PT symmetry leads optics to a completely different set of behaviors not predicted by conventional physics with only loss or only gain. The phenomena that occur at the “phase transition” are dramatic and hitherto unexpected, Yang says.

To make their optical diode, Sahin Kaya Ozdemir, PhD, a research scientist in Yang’s group and a key contributor to the paper, and Peng used two micro-resonators positioned so that light can flow from one to the other. One device is the “lossy” silica resonator.

The other incorporates the chemical element erbium into the silica structure for gain. Ozdemir says when erbium interacts with light of wavelength 1450 nm, it emits photons in the wavelength 1550 nm. A transmission detector set for 1550 nm will see a gain from this erbium-containing resonator.

When the rate of gain in one resonator exactly equals that of loss in the other, the phase transition occurs at a critical coupling distance between the resonators.

Most significantly, PT symmetry is broken, and the system shows a strong nonlinear behavior even at very weak input powers- input light gains intensity with a very steep non-linear slope. “As a result, time reversal symmetry is broken and light is able to move in only one direction— forward” says Yang.

“Time reversal symmetry is a fundamental physical rule that states that if light can travel in one direction, it must be able to travel in the opposite direction too. With this new optical diode, this is no longer the case,” says Ozdemir. “Engineers traditionally use magneto-optics and high magnetic fields to break time reversal symmetry, here we do this using strong nonlinearity enabled by broken PT symmetry. With an input of only 1 microwatt, we show 17-fold enhancement of light transmission in one direction. There is no transmission in the other direction. Such a performance would not be possible without the use of resonant structures and PT-symmetric concepts.”

“Our resonators are small enough to use in computers and future optical information processors. At present, we built our optical diodes from silica, which has very little material loss at the telecommunication wavelength. The concept can be extended to resonators made from other materials to enable easy CMOS compatibility.” Peng says.

“More broadly, our paper shows how a concept with its roots in mathematical physics can be utilized to provide solutions to practical problems, opening new possibilities for controlling and manipulating light on-chip,” the team says. “PT-symmetry breaking alone is not sufficient to have nonreciprocal response; operation in the nonlinear regime is also necessary. In the linear regime, light transmission is always reciprocal regardless of whether PT-symmetry is broken or not,” cautions the team.

Yang and Ozdemir believe that the PT concept can be extended to electronics, acoustics and other fields to create one-way channels, and photonic devices with advanced functionalities, and they are already working on new experiments relying on PT-symmetry.

###

Peng B, Ozdemir S, Lei F, Monifi F, Gianfreda M, Long G, Fan S, Nori F, Bender C, Yang L. Parity-time-symmetric whispering gallery microcavities. Nature Physics, April 6, 2014, advance online publication. DOI: 10.1038/NPHYS2927.

Funding for this research was provided by the Army Research Office and the U.S. Department of Energy.

The School of Engineering & Applied Science at Washington University in St. Louis focuses intellectual efforts through a new convergence paradigm and builds on strengths, particularly as applied to medicine and health, energy and environment, entrepreneurship and security. With 82 tenured/tenure-track and 40 additional full-time faculty, 1,300 undergraduate students, 700 graduate students and more than 23,000 alumni, we are working to leverage our partnerships with academic and industry partners — across disciplines and across the world — to contribute to solving the greatest global challenges of the 21st century.