At the time of year when many people have resolved to lose a few pounds, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are recruiting volunteers for a study to determine whether fasting from food a few days a week provides some of the same health benefits as severely limiting calories every day of the week.

For years, studies in laboratory animals have shown that sharply curtailing calories, while still getting adequate nutrition, can keep animals healthy and extend their lifespans. More recently, animal research has shown that fasting several days a week also prolongs life and prevents the development of diabetes, heart disease and certain types of cancer.

People who practice calorie restriction — eating a low-calorie yet nutritionally balanced diet — appear to receive some of the same benefits as animals, but few people are willing to severely restrict their calories, even for the promise of a potentially longer life.

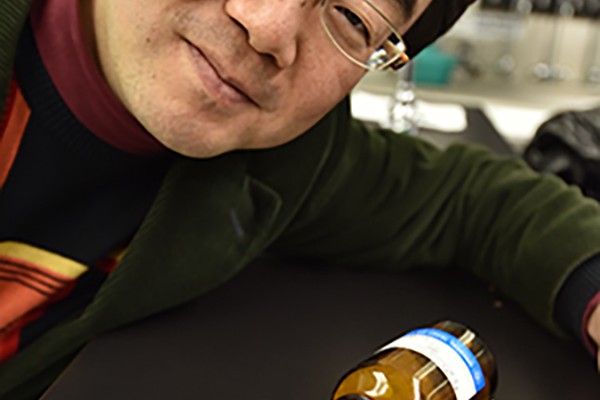

“We know there are benefits from calorie restriction, but the problem is people don’t want to do it. It’s too tough,” said Luigi Fontana, MD, PhD, research professor of medicine and the study’s principal investigator. “The good news is that data from animals show that intermittent fasting may be as effective as long-term calorie restriction in extending lifespan and improving health.”

In 2013, a British physician and journalist wrote a best-selling book and produced a documentary about the 5-2 diet, which calls for fasting two days a week and eating normally the other five. Now, thousands of people worldwide are trying it. But Fontana said intermittent fasting hasn’t been studied enough in people.

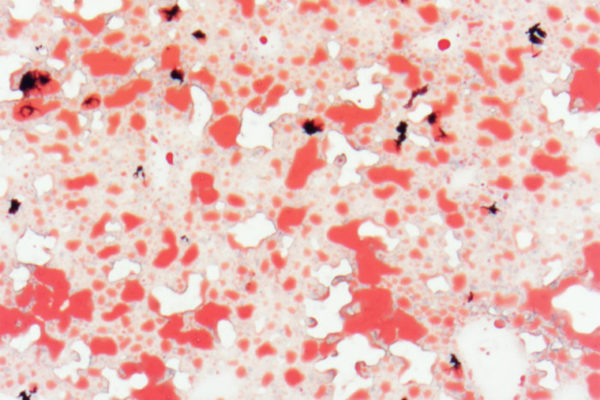

“This is going to be the first study of this strategy where we look comprehensively at markers of inflammation, changes in metabolic and cardiovascular function and health, including molecular changes in the colon that might protect against cancer,” Fontana said.

Instead of cutting calorie intake by 25 to 30 percent at every meal like practitioners of calorie restriction, those who participate in this study will be asked to fast for two or three days each week for at least six months.

Study volunteers whose body mass index (BMI, a measure of body fat based on height and weight) is 24 to 28, which is borderline overweight, will be asked to fast two days a week. Those with a BMI of 28 to 35, considered obese, will fast three days weekly.

“But participants won’t have to completely abstain from food on days they fast,” Fontana said. “At dinnertime, they can eat a large salad or raw or cooked green vegetables. But no protein or starchy vegetables like potatoes or bread are allowed. ”

On other days, study participants will consume the same number of calories they usually would.

“Our dietitian may suggest changes in the quality of participants’ diets but not in total calories,” Fontana explained. “We would like for them to eat healthier diets, to get rid of junk food and to eat high-quality foods, but we don’t want them to restrict calories.”

The study will last for a year. For the first six months, subjects will be randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first will fast two or three days each week. Participants in the other group will be asked to keep eating the way they usually do. Then, after six months, members of the second group also will fast two or three days per week.

All subjects will undergo testing at the start of the study. They will have blood drawn, receive a body composition test and have an oral glucose-tolerance test and an electrocardiogram. Visits and various tests also will be required three, six, nine and 12 months into the study. Some subjects also will be asked whether they want to undergo a colon biopsy to identify possible colon cancer risk.

As study subjects lose weight, Fontana’s team will monitor weight loss, but the study is less concerned with intermittent fasting’s effects on losing weight than with its relationship to changes connected to aging and longevity.

All study-related visits, tests and dietary consultations are provided free of charge. For more information or to volunteer, call the study coordinator, Shohreh Jamalabadi-Majidi at 314-362-2399 or email sjamalab@dom.wustl.edu.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.