It wasn’t what they were looking for — but that only made the discovery all the more exciting.

In January 2010, a team of scientists had set up two crossing lines of seismographs across Marie Byrd Land in West Antarctica. It was the first time the scientists had deployed many instruments in the interior of the continent that could operate year-round even in the coldest parts of Antarctica.

Like a giant CT machine, the seismograph array used disturbances created by distant earthquakes to make images of the ice and rock deep within West Antarctica.

There were big questions to be asked and answered. The goal, said Doug Wiens, PhD, was essentially to weigh the ice sheet to help reconstruct Antarctica’s climate history. (Wiens is a professor of earth and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and one of the project’s principal investigators.) But to do this accurately, the scientists had to know how the earth’s mantle would respond to an ice burden, and that depended on whether it was hot and fluid or cool and viscous. The seismic data would allow them to map the mantle’s properties.

In the meantime, automated-event-detection software was put to work to comb the data for anything unusual.

When it found two bursts of seismic events between January 2010 and March 2011, Wiens’ PhD student Amanda Lough looked more closely to see what was rattling the continent’s bones.

Was it rock grinding on rock, ice groaning over ice, or, perhaps, hot gases and liquid rock forcing their way through cracks in a volcanic complex?

Uncertain at first, the more Lough and her colleagues looked, the more convinced they became that a new volcano was forming a kilometer beneath the ice.

The discovery of the new as-yet-unnamed volcano is announced in the Nov. 17 advance online issue of Nature Geoscience.

Following the trail of clues

The teams that install seismographs in Antarctica are given first crack at the data. Lough had done her bit as part of the WUSTL team, traveling to East Antarctica three times to install or remove stations.

In 2010, many of the instruments were moved to West Antarctica, and Wiens asked Lough to look at the seismic data coming in, the first large-scale dataset from this part of the continent.

“I started seeing events that kept occurring at the same location, which was odd,” Lough said. “Then I realized they were close to some mountains, but not right on top of them.”

“My first thought was, ‘OK, maybe it’s just coincidence.’ But then I looked more closely and realized that the mountains were actually volcanoes and there was an age progression to the range. The volcanoes closest to the seismic events were the youngest ones.”

The events were weak and very low frequency, which strongly suggested they weren’t tectonic in origin. While low-magnitude seismic events of tectonic origin typically have frequencies of 10 to 20 cycles per second, this shaking was dominated by frequencies of 2 to 4 cycles per second.

Ruling out ice

But glacial processes can generate low-frequency events. If the events weren’t tectonic, could they be glacial?

To probe further, Lough used a global computer model of seismic velocities to “relocate” the hypocenters of the events to account for the known seismic velocities along different paths through the Earth. This procedure collapsed the swarm clusters to a third their original size.

It also showed that almost all of the events had occurred at depths of 25 to 40 kilometers (15 to 25 miles below the surface). This is extraordinarily deep — deep enough to be near the boundary between the earth’s crust and mantle, called the Moho, and more or less rules out a glacial origin.

It also casts doubt on a tectonic one. “A tectonic event might have a hypocenter 10 to 15 kilometers (6 to 9 miles) deep, but at 25 to 40 kilometers, these were way too deep,” Lough said.

A colleague suggested that the event waveforms looked like Deep Long Period earthquakes, or DPLs, which occur in volcanic areas, have the same frequency characteristics and are as deep. “Everything matches up,” Lough said.

An ash layer encased in ice

The seismologists also talked to scientists Duncan Young, PhD, and Don Blankenship, PhD, of the University of Texas, who fly airborne radar over Antarctica to produce topographic maps of the bedrock. “In these maps, you can see that there’s elevation in the bed topography at the same location as the seismic events,” Lough said.

The radar images also showed a layer of ash buried under the ice. “They see this layer all around our group of earthquakes and only in this area,” Lough said.

“Their best guess is that it came from Mount Waesche, an existing volcano near Mount Sidley. But that is also interesting because scientists had no idea when Mount Waesche was last active, and the ash layer sets the age of the eruption at 8,000 years ago.”

What’s up down there?

The case for volcanic origin has been made. But what exactly is causing the seismic activity?

“Most mountains in Antarctica are not volcanic,” Wiens said, “but most in this area are. Is it because East and West Antarctica are slowly rifting apart? We don’t know exactly. But we think there is probably a hot spot in the mantle here producing magma far beneath the surface.”

“People aren’t really sure what causes DPLs,” Lough said. “It seems to vary by volcanic complex, but most people think it’s the movement of magma and other fluids that leads to pressure-induced vibrations in cracks within volcanic and hydrothermal systems.”

Will the new volcano erupt?

“Definitely,” Lough said. “In fact, because the radar shows a mountain beneath the ice, I think it has erupted in the past, before the rumblings we recorded.”

Will the eruptions punch through a kilometer or more of ice above it?

The scientists calculated that an enormous eruption, one that released 1,000 times more energy than the typical eruption, would be necessary to breach the ice above the volcano.

On the other hand, a subglacial eruption and the accompanying heat flow will melt a lot of ice. “The volcano will create millions of gallons of water beneath the ice — many lakes full,” Wiens said.

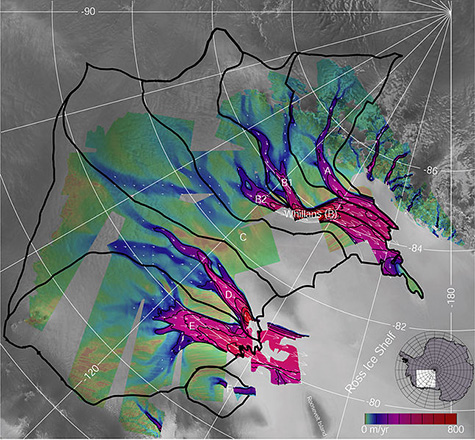

This water will rush beneath the ice toward the sea and feed into the hydrological catchment of the MacAyeal Ice Stream, one of several major ice streams draining ice from Marie Byrd Land into the Ross Ice Shelf.

By lubricating the bedrock, it will speed the flow of the overlying ice, perhaps increasing the rate of ice-mass loss in West Antarctica.

“We weren’t expecting to find anything like this,” Wiens said.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, Division of Polar Programs.