While many may see “taking Christ out of Christmas” as a recent phenomenon, the roots of secular Christmas celebrations and commercialization go deep into American history, says Anne Blankenship, PhD, a postdoctoral research associate at the John C. Danforth Center for Religion & Politics at Washington University in St. Louis.

Blankenship, who has taught courses on religion in America and the history of Christian traditions, has studied how Christmas celebrations have changed over time in the country, beginning with Colonial Puritans. The changes in Christmas celebrations have come in waves, beginning with the Puritan belief that Christmas should not be celebrated because it was not biblically mandated, resembled Catholic practices, and had nothing to do with their salvation and piety, she says. It epitomized the extraneous elements on the Christian calendar that they sought to eliminate. Baptists, Presbyterians and Quakers agreed, but the drunken carousing of 17th- and 18th-century Christmas celebrations thrived in New York and Anglican Virginia.

But in the 19th century, America’s increased consumerism and material production combined with romanticized notions of womanhood, childhood and the home led to new types of celebrations.

“All of these things play into the popularization of Christmas, especially as Puritan theocracy diminished,” she says. “Once they lost popular control, things loosened up considerably.” Ironically, denying the holiness of Christmas provided space for secular elements. Holiday celebrations were largely secular from the foundation of America, though some pastors lamented this fact from the beginning.

Another big change in Christmas celebrations came with the great influx of immigrants from Europe, who came to the U.S. for economic rather than religious reasons. They brought their own cultural traditions such as Christmas trees and gift giving, and it became trendy to imitate Victorian fashions. Our modern holiday developed in the latter half of the 19th century.

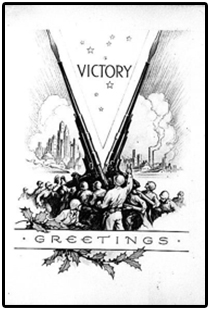

Patriotic notions of Christmas appeared as early as the Civil War when magazine illustrations depicted Santa in a Union Army uniform. This connection increased in 20th-century America during World War II, Blankenship says. In studying Christmas cards of the era, she says, one will find the typical snow-covered houses and quaint villages with light streaming from the windows, but with added graphic elements. For example, a giant star-spangled victory “V” towered over such a village on one card. On another, artillery guns formed a “V” sprouting from sprigs of holly.

“There was huge push during that time to keep celebrating Christmas because it symbolizes who we are as Americans — if we lose that, we lose what we’re fighting for,” Blankenship says. But the same message, she says, could be found in England and Germany.

Beginning around 1940, the secular and politicized nature of American Christmases led non-Christians, including Jews and Buddhists, to adopt some holiday traditions. So “Christmas” traditions became family traditions, she says. These celebrations were also a way to claim an American identity.

“In the 1940s and ‘50s, we saw this melting pot ideology where everyone was encouraged to share common traditions. Regardless who you were, you could quite literally buy into the traditions — if not the society — of the white, Christian majority. But beginning in the 1960s and the ethnic pride movements of the ‘70s, different groups said they didn’t want to celebrate Christmas in this way just because they were Americans. They said, ‘We can be American without imitating these practices.’”

In fact, Blankenship says, how we celebrate Christmas in America over the years has nearly become as much about our ideas of patriotism and politics as it has been about the birth of Jesus some 2,000 years ago. In her 2012 doctoral dissertation she looked at how Japanese Americans held in a World War II incarceration camp in rural Idaho used Christmas celebrations to simultaneously demonstrate patriotic loyalty and protest their current treatment.

“In the incarceration camps they celebrated Christmas as a specifically American holiday and used standard American motifs and icons like trees and cards to express their disappointment and discontentment with the government. They were saying, ‘We still want to be part of America; we celebrate your holidays, but we’re hurt by your actions.’”

Their patriotic celebrations were tinged with subtle messages of dissent, she says. While a typical Christmas card might show a snow-covered house with light coming out of the windows, the cards exchanged among those in the camps might show dark, grim, snow-covered barracks.

“At a glance, you would see a standard Christmas motif,” she says. “But within that, incarcerated Japanese Americans showed that things were not going well for them.”