Last month, Doug Wiens, professor of earth and planetary science in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, and two students were cruising the tropical waters of the western Pacific above the Mariana trench aboard the research vessel Thomas G. Thompson.

The trench is a subduction zone, where the ancient, cold and dense Pacific plate slides beneath the younger, lighter high-riding Mariana Plate, the leading edge of the Pacific Plate sinking deep into the Earth’s mantle as the plates slowly converge.

Taking turns with his shipmates, Wiens swung bright-yellow ocean bottom seismometers and hydrophones off the fantail, and lowered them gently to the water’s surface, as the ship laid out a matrix of instruments for a seismic survey on the trench.

The survey, which Wiens leads together with Daniel Lizarralde of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, will follow the water chemically bound to the down-diving Pacific Plate or trapped in deep faults that open in the plate as it bends. The work is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Scientists have only recently begun to study the subsurface water cycle, which promises to be as important as the more familiar surface water cycle to the character of the planet.

Hydration reactions along the subducting plate are thought to carry water deep into the Earth, and dehydration reactions at greater depths release fluids into the overlying mantle that promote melting and volcanism.

The water also plays a role in the strong earthquakes characteristic of subduction zones. Hydrated rock and water under high pressure are thought to lubricate the boundary between the plates and to permit sudden slippage.

http://youtu.be/2Pnq2OK9Svw

Dropping the instruments

Between Jan. 26 and Feb. 9, working day and night, watch-on and watch-off, the Thompson laid down 80 ocean bottom seismometers and five hydrophones.

The hydrophones, which detect pressure waves and convert them into electrical signals, provide less information than the seismometers, which register ground motion, but they can be tethered four miles deep in the water column where the bottom is so far down seismometers would implode as they sank.

The Thompson sailed over some of the most famous real estate in the world, the Mariana trench, which includes the bathtub-shaped depression called the Challenger Deep, to which Avatar director James Cameron plans to plunge in a purpose-built one-man submersible called the Deep Challenger.

Seven miles down, the pressure in the Deep is 1,000 atmospheres (1,000 times the pressure at sea level on dry land) or roughly 8 tons per square inch. Seismometers, says Wiens, only go down four miles.

The trench is created by the subduction of some of the world’s oldest oceanic crust, which plunges underneath the Mariana Isalnds so steeply at places that it is going almost straight down.

The active survey

After the Thompson returned to Guam and Wiens flew back to St. Louis to resume his less romantic duties as chair of the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, the research vessel Marcus G. Langseth began to sail transects above the matrix of seismometers, firing the 36-airgun array on its back deck.

The sound blasts reflected from the boundaries between rock layers a few miles beneath the ocean floor were picked up by an five-mile-long “streamer,” or hose containing many hydrophones, towed just beneath the surface behind the ship.

This was the “active” stage of a seismic survey with a “passive” stage yet to come.

After the seismic survey, the Langseth returned to pick up 60 seismometers, leaving behind 20 broadband seismometers and the hydrophones that will listen for a year to the reverberations from distant earthquakes, allowing the seismologists to map structures as deep as 60 miles beneath the surface.

In the meantime Patrick Shore, a research scientist in earth and planetary science, and two Washington University students had set sail across the ocean in a tiny vessel, the Kaiyu III, to install seismometers on the Mariana islands that will also supply data for the “passive” stage of the survey.

Water, water everywhere

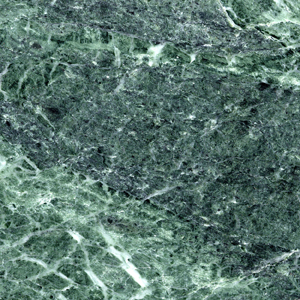

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Water plays a completely different role at depth than it does on the surface of the Earth. Water infiltrating the mantle through faults hydrates the mantle rock on either side of the fault.In a low temperature process called serpentinization, it transforms mantle rock such as the green periodotite into serpentinite, a rock with a dark scaly surface like a serpent’s skin.

As the slab plunges yet deeper, dehydration reactions release water, which at such great pressure and temperature exists as a supercritical fluid that can drift through materials like a gas and dissolve them like a fluid. The fluid rises into the overlying mantle where it lowers the melting point of rock and triggers the violent eruptions of magma that created the Mariana Islands, to which Shore was sailing.

“We think that much of the water that goes down at the Mariana trench actually comes back out of the earth into the atmosphere as water vapor when the volcanos erupt hundreds of miles away,” Wiens says.

The scientists will map the distribution of serpentinite in the subducting plate and overlying mantle, by looking for regions where certain seismicwaves travel more slowly than usual.

Tracing the water cycle within subduction zones will allow the scientists to better understand island-arc volcanism and subduction-zone earthquakes, which are among the most powerful in the worldBut the role of subsurface water is not limited to these zones. Scientists don’t know how subduction got started in the first place, but water may be a necessary ingredient. Venus, which is in many ways similar to Earth, has volcanism but no plate tectonics, probably because it is bone dry.