Staying awake slows down our brains, scientists have long recognized. Mental performance is at its peak after sleep but inevitably trends downward throughout the day, and sleep deprivation only worsens these effects.

|

|

WUSM researchers recently showed that subtly altering a part of the fruit fly’s brain linked to learning and memory can keep the fly mentally sharp even after it has been deprived of sleep.

|

For the first time, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found a way to stop this downward slide. When scientists genetically tweaked a part of the brain involved in learning and memory in fruit flies, the flies were unimpaired even after being deprived of sleep.

“The ultimate goal is to find new ways to help people like the armed forces and first responders stay alert and on top of things when they have to be awake for extended periods of time,” says senior author Paul Shaw, Ph.D., assistant professor of neurobiology. “We have drugs now that can keep people awake, but they’re addictive and lose their effectiveness with repeated use. This research should help us find methods for maintaining mental acuity that have more specific effects, are less addictive and retain their potency.”

The results appear in Current Biology on Aug. 5.

Shaw’s lab was the first to show that fruit flies enter a state of inactivity comparable to sleep. They demonstrated that the flies have periods of inactivity where greater stimulation is required to rouse them. These periods begin at night; like human sleep they are cyclic over the course of the night, with sleep cycles lasting 20-25 minutes. Also like humans, flies deprived of sleep one day will try to make up for the lost time by sleeping more the next day, a phenomenon referred to as increased sleep drive or sleep debt.

For the new study, first author Laurent Seugnet, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow, revealed that sleep deprivation impairs learning in flies. Seugnet put them through multiple runs of a maze with two options: one lighted vial with the bitter-tasting quinine in it and one darkened but quinine-free vial. Flies are instinctively drawn to light, but they want to avoid the unpleasant taste of quinine.

“This tests the flies’ mental capacity in two ways: First, they’ve got to remember that the lighted vial is the one that has quinine in it, and then they’ve got to suppress their natural instinct to fly toward the light,” says Seugnet.

Flies allowed normal sleep learned to avoid the lighted vial, but sleep-deprived flies did not.

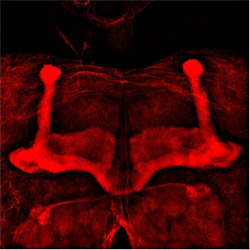

A brain messenger known as dopamine is linked to some of the mental capabilities harmed by sleep loss. Researchers decided to test if this messenger could be used to block learning impairment in sleep-deprived flies. Seugnet genetically altered a line of flies so they made more copies of a dopamine receptor in brain regions known as the mushroom bodies. These areas are roughly equivalent to the human hippocampus, which is involved in learning and memory.

Sleep-deprived flies with extra dopamine receptors could still learn as if they had a full night’s sleep, Seugnet found.

“Using this gene and other related genes, we may be able to find better ways to boost performance for someone like a relief worker who’s had to stay awake for six straight days trying to save people trapped by an earthquake,” Shaw says.

“I want to emphasize, though, that this type of treatment would just be for people who absolutely have to stay awake,” he adds. “It’s not about trying to cram too many hours in your day—everyone else should just suck it up and get a good night’s sleep.”

Shaw is currently examining the role of related genes in sleep and learning. He is also testing whether sleep deprivation in young flies impairs brain development.

Seugnet L, Suzuki Y, Vine L, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. D1 Receptor activation in the mushroom bodies rescues sleep loss induced learning. Current Biology, online July 31.

Funding from the NIH Neuroscience Core Blueprint Grant and the McDonnell Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.