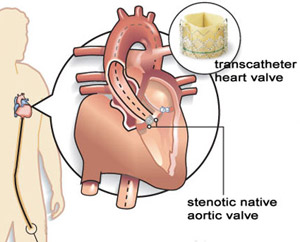

In a nationwide clinical trial, physicians are testing an investigational device that allows them to insert replacement aortic valves without opening the chest or using a heart-lung machine, making the procedure available to high-risk and formerly inoperable patients. Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has been selected as a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigative site in the trial evaluating this technique, which uses a catheter to thread a replacement aortic valve into the heart — a far less invasive procedure than the standard open-heart surgery.

“This has the potential to supplant the open procedure for high-risk patients,” says Ralph J. Damiano Jr., M.D., the John Shoenberg Professor of Surgery and chief of cardiac surgery at the School of Medicine and a cardiac surgeon at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

If the device lives up to that potential, it could benefit many of the approximately 200,000 patients per year in the United States who need a new heart valve because they have severe aortic stenosis, a narrowing of the aortic valve, which normally ensures the efficient flow of blood out of the heart and into the body. Severe aortic stenosis can lead to congestive heart failure and sudden death.

The clinical trial, called the PARTNER trial (Placement of AoRTic traNscathetER valves), will eventually enroll about 600 patients at up to 15 sites across the United States. The device, developed by Edwards Lifesciences, consists of a heart valve made of cow heart tissue attached to a collapsible mesh cylinder. Mounted on a catheter, the collapsed valve can be guided through the patient’s circulatory system from the leg or inserted between the ribs into the heart and expanded at the site of the patient’s diseased valve. The technique is called transcatheter valve replacement.

“Partner” also signifies the partnership between a cardiac surgeon and an interventional cardiologist, both of whom participate in each patient’s procedure. Interventional cardiology is a specialty that deals with the catheter-based treatment of structural heart diseases.

In addition to Damiano, physicians conducting the trial at the School of Medicine are John M. Lasala, M.D., Ph.D., professor of medicine and medical director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory; Nader Moazami, M.D., associate professor of surgery and chief of cardiac transplantation; and Alan Zajarias, M.D., assistant professor of medicine in the cardiovascular division.

“Open-heart surgery for aortic valve replacement is a very common procedure, but many of those who need it are too old or too sick to qualify for the surgery,” Damiano says. “That fact led to the development of these transcatheter valves. An earlier, small feasibility study showed that the mortality rate with the valves was nearly as low as that of conventional valve replacement surgery — around 10 percent.”

The transcatheter technique does not require stopping the heart and placing the patient on a heart-lung bypass machine, so frailer or sicker patients can tolerate the procedure. Without valve replacement, the life expectancy of patients with severe aortic stenosis is very short, usually less than five years.

Two groups of patients will take part in the PARTNER trial. The surgical arm of the trial will consist of patients with severe aortic stenosis who are considered at high-risk because of their disease, but who nevertheless are candidates for conventional open-heart surgery. The other arm will consist of patients with severe aortic stenosis who are considered inoperable because they are unlikely to survive open-heart surgery.

In the surgical arm, patients will be randomly assigned to receive either the transcatheter valve or to undergo a conventional valve replacement in which the chest cavity is opened and a new valve is sewn into the heart. In the other arm of the trial, patients will be randomly assigned to receive either the transcatheter valve or appropriate medical therapy.

Success in the surgical arm is achieved if the clinical results demonstrate that the transcatheter heart valve is not statistically inferior to conventional open-heart surgery. The clinical results of the other arm need to demonstrate that the transcatheter heart valve is statistically superior to medical management.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.