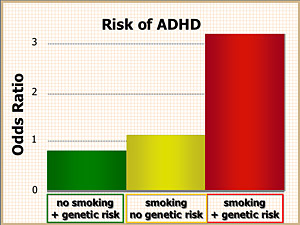

Past research has suggested that both genes and prenatal insults — such as exposure to alcohol and nicotine — can increase the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). But the identified increases in risk have been very modest. Now, a team of Washington University scientists has found that when those factors are studied together, risk of a severe type of ADHD greatly increases.

The investigators looked at two genes related to ADHD risk and considered whether mothers smoked during pregnancy. In past studies, maternal smoking had been linked to a 1.2- to 1.3-fold increase in risk of ADHD. Genes associated with ADHD elevated risk between 1.2- and 1.4-fold.

“But when we looked at the effect of maternal smoking in children with one of our candidate genes, we saw a three-fold increase in risk, and in children with both genes whose mothers smoked during pregnancy, we saw a nine-fold increase,” says senior investigator Richard D. Todd, M.D., Ph.D., the Blanche F. Ittleson Professor and director of the Division of Child Psychiatry at Washington University. “Our findings begin to offer an explanation for the modest effects we’ve seen when looking at genes or environmental variables one at a time. It appears it’s really the interaction of genes and environmental factors that predisposes a child to problems with ADHD.”

Todd’s team reports its findings online in the journal Biological Psychiatry. The study also will appear in an upcoming print issue of the journal.

The researchers studied children from 782 Missouri families, gathering information on 1,540 twins between 7 and 18 years of age. A parent from each family, usually the mother, completed diagnostic interviews about both twins to determine whether either had ADHD symptoms or other behavioral problems. The researchers also studied DNA from twins in 557 of those families. The mothers were asked about smoking and complications during their pregnancy.

“Almost 25 percent of the mothers said they had smoked when they were pregnant,” says lead author Rosalind J. Neuman, Ph.D., research professor of mathematics in psychiatry. “We classified mothers as smokers if they reported smoking at all while pregnant, and we think that’s fairly representative because of those who reported smoking at all during pregnancy, 75 percent continued to smoke during all three trimesters, and another 10 percent smoked in two of the three trimesters.”

In this study, Neuman, Todd and their colleagues concentrated on two of the candidate genes linked to ADHD risk in past research. One was the DRD4 gene on chromosome 11 and the second was the DAT1 gene on chromosome 5. Both genes are part of the brain’s dopamine system, and animal studies have shown that dopamine activity is related to attention. Common variants in both genes have been linked to small increases in ADHD risk.

“We looked at these particular genes because stimulant medications used to treat ADHD are known to increase dopamine at synapses between brain cells, and that’s where the protein products of these genes are located,” Todd explains. “These same cells also possess the nicotinic receptors that smoking activates, which also increases dopamine.”

There are 18 diagnostic symptoms that can go into an ADHD diagnosis, nine involving attention and nine involving hyperactivity and impulsivity. Under the current criteria in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), a child must have six or more symptoms to have a diagnosis of ADHD.

A child with at least six inattentive symptoms is classified as inattentive. Six or more of the hyperactive symptoms classifies a child as hyperactive. Six or more from both categories is known as the combined subtype of ADHD. Children with the DRD4 and DAT1 genes whose mothers smoked during pregnancy tended to be at risk for that severe, combined subtype.

Interestingly, even children who didn’t officially have ADHD did have more symptoms of the disorder if they had been exposed to cigarette use in utero or had the genetic variations related to risk.

“There were statistically significant differences just comparing the number of ADHD symptoms a child had when the mother smoked versus the number of symptoms in kids whose mothers didn’t smoke during pregnancy,” Neuman says. “We also found that whether or not they actually met diagnostic criteria for ADHD, kids prenatally exposed to cigarette smoke who had a risk variant in either their DRD4 or DAT1 gene also had more symptoms.”

Neuman and Todd say those children might be thought of as having sub-syndromal forms of ADHD, too mild to be diagnosed officially but probably related to both their genetic makeup and to prenatal exposure to cigarettes. In future studies, they hope to gather more data, such as whether either the mother or father have ADHD symptoms themselves or whether children are growing up in houses where both mother and father smoke, potentially affecting brain development. And as the studies continue, the investigators plan to focus on the interplay of genetic and environmental factors rather than considering them separately.

“The important thing we’ve learned is that the risks were not just cumulative, but they were interactive,” Todd says. “It’s the interplay of genetic and environmental effects that seems to determine which children develop ADHD, so in future studies we want to focus on that interaction.”

Neuman RJ, Lobos E, Reich W, Henderson CA, Sun LW, Todd RD. Prenatal smoking exposure and dopaminergic genotypes interact to cause severe ADHD subtype. Biological Psychiatry, DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.049

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.