Pengcheng Wang is one of many STARS.

The Parkway South (St. Louis County) High School senior is one of 61 high-school participants in a novel program for scientifically inclined students.

The 2006 Pfizer-Solutia Partnership of Universities’ Students and Teachers as Research Scientists (STARS), a program for gifted high-school students in the area, has once again given high school students and researchers the rare opportunity to work together for an enriching and productive summer.

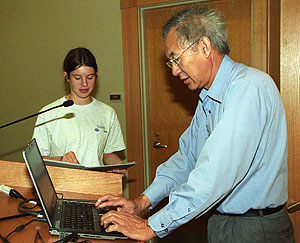

The program, in its 17th year, pairs students and teachers with research mentors at WUSTL, the University of Missouri-St. Louis, Saint Louis University, the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center and the Missouri Institute of Mental Health. The six-week program culminated July 21 with the high-school students giving oral presentations detailing their summer projects.

Wang, a rising senior at Parkway South, worked under the tutelage of Shirley J. Dyke, Ph.D., the Edward C. Dicke Professor of Civil Engineering and director of the Structural Control and Earthquake Engineering Laboratory, and said he had an earth-shattering experience.

“I’ve really enjoyed it,” he said. “It’s allowed me to get involved in something that I wouldn’t normally get to do.”

What has truly surprised and delighted him about civil engineering is the blend of science and technical/computer work involved in his research.

He was grateful for computer assistance from Chenyang Lu, Ph.D., assistant professor of computer science and engineering, and his students.

His research in Dyke’s lab has been a smaller portion of a larger project, one that involves demonstrating the efficacy of wireless sensors in structural health monitoring of buildings.

The wireless sensors, about a square inch in size, are attached to the sides of buildings to monitor the force of sway when shaking, similar to an earthquake, occurs.

The sensors are then transmitted to a computer program that translates the random units read by the sensors into units useful for the engineers and computer programmers.

The computer sends a message to magnetorheological dampers, or MR dampers, that are within the building’s structure to dampen the effect of the swaying on the structure.

MR dampers act like shock absorbers for a building.

Filled with a fluid that includes suspended iron particles, the MR dampers lessen the shaking by becoming solid when an electrical current (turned on by the computer, which has been alerted to the swaying by the sensors) is run through the MR dampers, aligning all of the iron particles.

Dyke was the first civil engineer to demonstrate the use of MR damper technology for structural health monitoring and protection of buildings during seismic movement.

Last year’s STARS student in Dyke’s laboratory also worked on the wireless sensors.

Wang has been continuing and amplifying the knowledge about the efficacy of wireless sensors versus wired sensors for structural health monitoring. Wireless sensors are much less expensive than wired sensors, and considerably more flexible and convenient.

“It’s been a new experience,” Wang said. “In our different high-school science labs, you can examine each experiment and figure out what went wrong. In research, it’s a lot tougher. Sometimes, you have no idea what is wrong.”

That sort of real-world knowledge about how scientific research is conducted allows each high-school student to truly experience the world of science.

“This program is unique because students are introduced to hands-on opportunities to address real-world problems, exposing them to basic research, creativity and the struggles of discovery,” said Ken Mares, of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, who directs the STARS program.

As a result of their summer experiences, many STARS students are considering careers in medicine, science and technology.

Wang, like Robert Frost, prefers the road lesss traveled by — perhaps a math or aerospace engineering degree is in his future.

“Pengcheng has been an outstanding contributor to the research team this summer and his involvement made it possible to complete the project on time,” Dyke said.

“It is clear that the STARS program is beneficial not only to the student researchers, but also to the University and department.”

In the current science education climate, allowing students to experience basic science research and then to encourage the pursuit of scientific careers is crucial.

In fact, students who have participated in the STARS program in years past often come back to work with their specific researcher, or other researchers that they had an opportunity to meet through the program.

Wang is not sure where he’ll be attending college, but he knows that he will no longer have a shaky understanding of civil engineering, MR dampers and wireless sensors for structural health monitoring, thanks to the STARS program.