You’re late for work and up ahead traffic is backing up. You know you’re never going to make the 11 a.m. deadline for that big report. Plus, you skipped breakfast and you suspect you’re getting the flu.

You’re suffering from stress — both psychological and physical.

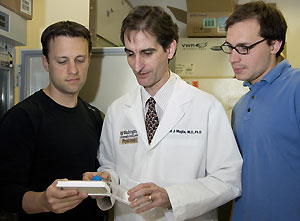

Louis J. Muglia, M.D., Ph.D., understands stress at a level most people can’t. While projecting a decidedly stress-free and calm demeanor, Muglia spends much of his time thinking about the stress response. He is investigating the factors that turn on and off the signals regulating hormone release from the adrenal glands, where “stress hormones” are made.

Muglia, associate professor of pediatrics, of molecular biology and pharmacology and of obstetrics and gynecology, came to the School of Medicine in 1996 with a bachelor’s degree in biophysics from the University of Michigan and a doctorate and medical degree from the University of Chicago. Attracted early to the lab bench, he was continually involved in research projects during his education and training.

“In fact, after I graduated from Chicago and went into my pediatrics residency at Children’s Hospital in Boston, I short-tracked into a fellowship program,” he says. “I wanted to be able to get back into a laboratory as quickly as I could.”

In the spirit of the true physician-scientist, he looked for research that would allow him to continue investigating basic science but that could be adapted to questions that would arise in his clinical practice.

“Lou is an outstanding clinician, a gifted educator and a creative and passionate investigator,” says Alan Schwartz, Ph.D., M.D., the Harriet B. Spoehrer Professor and head of pediatrics and professor of molecular biology and pharmacology. “Lou is the real deal — a triple-threat physician-scientist of the 21st century.”

That appellation is echoed by another of Muglia’s colleagues, Jonathan Gitlin, M.D., the Helene B. Roberson Professor of Pediatrics and professor of genetics, who calls Muglia the quintessential physician-scientist.

Because he practices in the field of pediatric endocrinology, many of Muglia’s young patients have disorders of the pituitary and adrenal glands, which have among the most devastating of effects.

“I want to understand better how to treat disruptions in the areas that control stress hormones,” he says. “We’ve begun to see how such disruptions extend to other diseases like depression and autoimmune disorders. It’s an area that spans disciplines and affects many, many people.”

The stress response occurs when the hypothalamus, a small region of the brain that sits just above the sinus cavities, receives signals that the body is under stress — signals that say “virus attack!” or “low blood sugar!” or “danger ahead!” The hypothalamus then alerts the pituitary gland, which in turn tells the adrenal gland to secrete stress hormones.

“The adrenal hormones affect every tissue in the body,” Muglia explains. “So they influence many disease processes, and we don’t yet have a complete understanding of how large their impact is.”

In the course of their work on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal mechanism, Muglia and his research team have found that certain adrenal hormones, called glucocorticoids, exert strong effects on the immune system.

“If a person’s immune system lacks the ability to properly respond to stress levels of glucocorticoids, it can over-respond to infection, and the inflammatory response won’t shut off after the infection is gone,” Muglia says.

Chronic inflammation has proven to be a source of many degenerative diseases and autoimmune disorders such as asthma, arthritis, lupus and inflammatory bowel disease.

Nerves in the brain also respond to the glucocorticoid hormones, and Muglia has found that impairment of this response leads to despair-like behaviors in lab mice, behaviors very much like those that depression causes in people. According to Muglia, these findings suggest that an important therapeutic target for new treatments for depression is the brain receptors that react to glucocorticoids.

Muglia also would like to better define the genes that are activated or repressed by glucocorticoids. Steroids such as glucocorticoids are among the most commonly used drugs, and they are prone to numerous side effects. Muglia believes research into the genes affected by glucocorticoids could reveal a way to limit the “bad” targets of glucocorticoids while maintaining the “good” targets.

Muglia’s training as a pediatrician has fueled his interest in another area of research — preterm birth. He notes that the number of preterm births in the United States has risen inexplicably by 20 percent in the past two decades, now complicating 12 percent of pregnancies.

It turns out that many of the components of the stress response pathway are involved in determining when a baby is born. Muglia’s research aims to better predict who will go into preterm labor and better treat preterm labor once it starts.

Muglia enthusiastically points out how much his research depends on the members of his laboratory, which include students from neurosciences, immunology and molecular cell biology programs, postdoctoral fellows and his senior technician of 10 years, Sherri Vogt.

“To me the highlight of Washington University has been phenomenal colleagues at the faculty, postdoctoral and student levels,” Muglia says. “The students have been absolutely great. It’s fun to come in every day and see how well they do.”

Muglia said he feels he had excellent mentors as he made his way through his degree programs and wants to give back in kind. He has received special recognition awards for mentorship from the Graduate Student Senate on four occasions and was also named Outstanding Teacher in General Pediatrics in 2004.

“These honors mean a tremendous amount to me,” Muglia says. “And being division director of pediatric endocrinology and one of the unit leaders of the developmental biology and genetics unit has given me further great opportunities to mentor very talented people coming through the pediatrics clinical and research environments.”

|

Louis J. Muglia Family: Wife, Lisa; daughter, Sarah (20); son, Peter (18) Years at the University: 10 Hobbies: Wine and cooking: “In my family, we do a tremendous amount of cooking together. We try anything”; music and poetry: “In a previous life, I was an aspiring classical guitarist. I still have my four guitars”; tennis with his son: “That’s my main athletic recreation.” About his work as physician, researcher, teacher and mentor: “Some days it seems a little overwhelming, but I can see doing nothing else.” |

Even though he runs his own lab now, Muglia knows that he still benefits from faculty members who serve as his mentors. Muglia names Schwartz as a strong influence on his science, saying he has been a fantastic mentor to him. Equally, Muglia praises Gitlin for his scholarly guidance. Both have shown keen insight and great breadth of understanding, according to Muglia.

“I am truly honored to count Lou among my very closest colleagues,” Gitlin says. “He has a passion for excellence in the scientific pursuit of new knowledge, a compassionate and gifted approach to patient care and teaching and a devotion to the obligations of citizenship that make a department great.”

“We are so very proud to count him among our faculty and institutional leaders,” Schwartz says.

When not devoting time to his work at the School of Medicine, Muglia spends his time with his family. He has been married for 22 years to Lisa Muglia, Ph.D., research associate in pediatrics. Lisa Muglia has worked in her husband’s lab almost since the two moved to St. Louis.

“She’s been a great asset to the lab,” Muglia says. “But I probably talk less with her than anyone else in the lab because I know I’ll catch up with her at home.”

The couple has two children. Their daughter, Sarah, will be 21 this year and attends Beloit College in Wisconsin where she’s studying French and religious studies. Their son, Peter, is a senior in high school and plans to attend George Washington University in the fall. His interests lie in the study of history.

Asked about not having any scientific offspring, Muglia gives a tongue-in-cheek answer: “I haven’t given up yet.”

But then he continues, “Whatever makes them happy and however they feel they can impact the world is great with me.”

No stress there.