Scientists have long recognized that plaque deposits in the brain characterize Alzheimer’s disease, but a way to detect them in living people has remained frustratingly out of reach for many years. Until now, scientists have been able to study the plaques only after death via post-mortem dissections of patient brains, the technique that first led to the discovery of plaques 100 years ago.

The new imaging agent, informally known as PIB (for Pittsburgh compound-B), was developed by William Klunk, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of psychiatry; Chet Mathis, Ph.D., professor of radiology, and others at the University of Pittsburgh. It is used in conjunction with PET scanning to open new windows into the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease. It also may assist in the development and assessment of treatments that may slow or stop the condition.

“In the early stages when you would want to start treatment, many of the changes of Alzheimer’s disease are actually fairly mild,” says Mark Mintun, M.D., professor of radiology and of psychiatry. “If we could detect the early development of the plaques with a scan, we’d not only be able to start treatment sooner, we might even be able to slow or stop the development of the plaques before substantial damage occurred.”

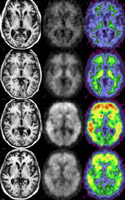

PIB sticks to amyloid plaques in the brain. In a person lacking amyloid, the agent washes out of the brain in 30 to 60 minutes. In a person with amyloid, PIB stays longer, creating a strong contrast that PET scans can detect easily.

“When this test is positive, it’s dramatically visual,” says Mintun, who is directing a new PIB study at Washington University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC).

In conjunction with Mintun and John C. Morris, MD, director of the ADRC, Washington University researchers Robert H. Mach, Ph.D., professor of radiology; Carmen S. Dence, research scientist in radiology; and postdoctoral fellow Sang Yoon Lee, Ph.D., began working with PIB’s creators in November 2003 to develop a safe and efficient method for regular production of the new compound at Washington University. Their rapid success allowed the ADRC to begin using the new agent for scans in April 2004.

Early studies of PIB’s potential will focus both on those already diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and on others with no signs of cognitive impairment.

“Identifying people at risk before they develop clinical symptoms of the condition is one of the most important things we may be able to accomplish with PIB,” Mintun says. “To do that, it’s really crucial to have an ADRC like ours where we can follow people on a yearly basis.”

Future studies of PIB may include testing its usefulness as a gauge of new treatments designed to clear amyloid from the brain.

“This is not a done deal yet, but the early results are very promising,” Mintun says.

Funding from the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, the Dana Foundation and the National Institute on Aging supports this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked second in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.