H.W. Janson (1913-1982) is among the 20th century’s most influential art historians. Since 1962, his textbook History of Art, now in its sixth edition, has been used in countless college surveys and sold 4 million copies in 14 languages.

Yet Janson, who immigrated to the United States from Germany in the mid-1930s to protest Nazi cultural policies, remains little-known in his former country.

That’s about to change, thanks to Exile and Modernism: H.W. Janson and the Collection of Washington University in St. Louis, a touring exhibition organized by the University’s Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum.

Over the next two years, Exile and Modernism — which builds on a similar show the University presented in 2002 at the Salander- O’Reilly Galleries in New York — will travel to four German museums and one in the United States. The exhibition documents how Janson, as curator at the University in the mid-1940s, employed prescient vision, a modest acquisitions budget and contacts among the exile art community to build what he proudly called “the finest collection of contemporary art assembled on any American campus.”

“Janson’s story is not known in Germany; he is a rediscovery,” said Sabine Eckmann, Ph.D., curator of the Kemper Art Museum and a native of Germany. However, “there is a lot of German interest in exile, in all of these artists and all of these artworks that were lost. It’s part of Germany’s art history.

“Exile and Modernism demonstrates what one exile art historian was able to do in the United States at a time when modern art was banned as degenerate in Germany,” continued Eckmann, a specialist in exile art. “It also offers a chance to rethink the meanings of concepts like ‘exile’ and ‘modernism’ and their connection to one another.

“We typically see exile as an experience of loss or isolation, but Janson shows that exile can produce creative energies. There’s an interesting dialog between his experience of Nazi culture, which caused him to react to certain strains of modern art, and his new orientation in America.”

In all, Exile and Modernism will feature close to 50 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, works collected both by Janson and by subsequent curators fulfilling his thematic architecture.

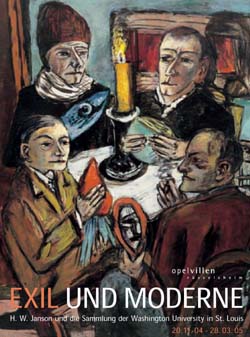

Highlights include Pablo Picasso’s early collage Glass and Bottle of Suze (1912); Juan Gris’ Still Life With Playing Cards (1916); Georges Braque’s Still Life With Glass (1930); and Max Beckmann’s Four Men Around A Table (1943-44).

Other artists include Alexander Calder, Willem de Kooning, Theo van Doesburg, Jean Dubuffet, Max Ernst, Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston, Marsden Hartley, Paul Klee, Ferdinand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Matisse, Ludwig Meidner, Joan Miró, Jackson Pollock and Yves Tanguy.

Prior to heading overseas, an abridged version of Exile and Modernism will run Aug. 17-Oct. 24 at the Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum in San Antonio.

The full show will then open Nov. 19 at the Stiftung Opelvillen, Zentrum fuer Kunst near Frankfurt, where it will remain on view through March 28.

Subsequent venues include the Angermuseum Erfurt in the former East Germany; the Kunsthalle St. Annen, Luebeck; and finally the Museum Fuer Neue Kunst, Freiburg, where it will coincide with the 2006 Basel Art Fair.

Braus Editions will release a German-language version of the Salander-O’Reilly exhibition catalog. The volume will feature new pieces by German scholars, including an essay by Beate Kemfert, co-organizer of the German tour, as well as Eckmann’s essay “Exilic Vision,” a consideration of Janson’s emigration and views on contemporary art, and a previously unpublished lecture by Janson recounting his years in St. Louis.

H.W. Janson

Born in 1913 in St. Petersburg, Russia, Janson was raised in Hamburg, where his family settled after fleeing the October Revolution of 1917. He began his university education in Munich in 1932 but transferred the following year to Hamburg University, studying with Erwin Panofsky until the influential professor’s firing by National Socialists.

Janson arrived at Washington University in 1941 as an assistant professor of art history. At the time, public awareness of the University collection was almost nonexistent. Though established in 1881, the collection lacked on-campus facilities and was held in storage at the City Art Museum (CAM, now the Saint Louis Art Museum).

Janson only discovered the collection, then mostly 19th-century American and European painting and applied arts, through a close reading of CAM’s wall labels.

Janson was named curator of the University collection in 1944 and immediately organized a makeshift gallery in the School of Architecture.

His boldest stroke came the following year, when he raised about $40,000 by de-accessioning 120 paintings and more than 500 additional objects.

Ironically, more than half the funds, about $23,000, came from the controversial sale of Frederic Remington’s Dash for Timber, a scene of the American West.

Over the next year, Janson used those monies to acquire some 40 major works of European and American modernism, putting special emphasis on cubism, constructivism and surrealism. He worked primarily with exile dealers, including Paul Rosenberg, Karl Nierendorf and especially Curt Valentin, as well as the former expatriate American Peggy Guggenheim.

Janson left campus in 1948, but subsequent curators such as Frederick Hartt and William N. Eisendrath Jr. — working with prominent local collectors — continued to build on his curatorial architecture.