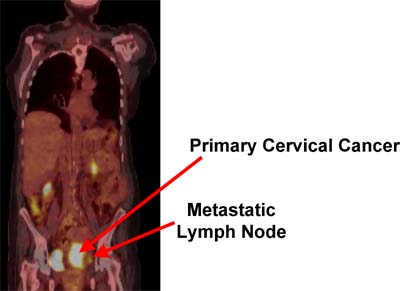

Radiologists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown that post-treatment positron emission tomography (PET) scans can be used to predict cervical cancer patients’ chances of survival.

PET scans are used regularly to diagnose cervical cancer, but post-therapeutic PET scans are not covered by most insurance plans and are rarely used to look for signs of cancer recurrence. Current follow-up practices include regular pelvic exams and occasional X-rays or CAT scans.

According to researchers, the new study’s results suggest that making post-treatment PET scans standard practice could give doctors a potentially lifesaving head start at prescribing follow-up therapy.

Their results appear in the June 1 issue of Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“X-rays and CAT scans have not been proven to have any accuracy in detecting recurrence of cervical cancer,” says Perry W. Grigsby, M.D., professor of radiology and of radiation oncology at the School of Medicine. “Right now, we’re forced to wait until a patient comes back with a lump or with symptoms before we can begin follow-up treatments, and by then it’s often too late.”

X-rays and CAT scans reveal structural details of the body, but PET scans — originally developed at Washington University School of Medicine in the 1970s — can detect functional differences in tissues, allowing physicians to highlight tumors.

Perry Grigsby

Grigsby and colleagues retrospectively examined PET scans from 152 cervical cancer patients taken after their treatment at the Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital. They used data from the scans to separate cervical cancer patients into three groups: those with little or no sign of continued cancer, those with moderate signs of recurrence or continuation, and those with strong signs that therapy had failed to eliminate all tumors.

Classification in one of those groups was a powerful predictor of patient outcome. After five years, 90 percent of the patients in the group with few signs of continued cancer were still alive, while less than half in the group with strong signs of surviving tumor cells had survived.

“The hope is that we might be able to catch patients in that second or third group before their cancers get too far ahead of us and try to do something to make their survival rates better,” Grigsby says. “This study doesn’t prove that we can change those survival rates, but it does definitively show that we can accurately check whether the initial treatment worked.”

Grigsby PW, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Rader J, Zoberi I. Posttherapy FDG-PET in carcinoma of the cervix: response and outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology, June 1, 2004.

The full-time and volunteer faculty of Washington University School of Medicine are the physicians and surgeons of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked second in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.