Growing up practically next door to the National Institutes of Health, Alexander W. Dromerick, M.D., became fascinated with science at a young age. But it wasn’t long before he realized that the people behind the science are what ultimately motivate him.

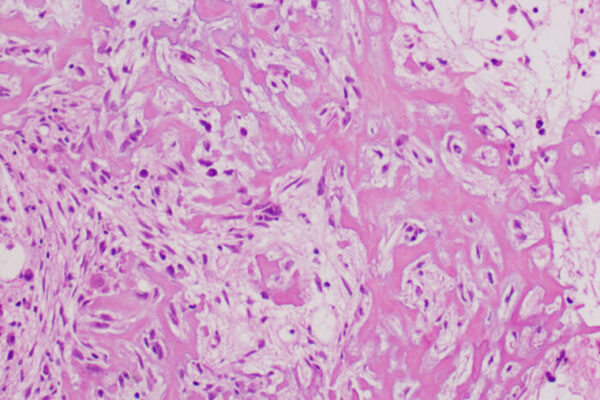

His commitment to patient care was further reinforced by his own experience as a critically ill patient. By battling bone cancer while making his way through medical school, he experienced life as a patient while simultaneously learning to be a doctor. And that allowed him to gain a profound insight into health care.

“My oncologist did a great job of curing my cancer, but the folks in rehabilitation really helped me a lot, both as a patient and as a doctor,” Dromerick says. “They helped me understand that it takes more than medication to take good care of a sick person.”

Now, as an associate professor of neurology, of occupational therapy and of physical therapy, Dromerick has found an ideal way to channel his love of science toward caring for people.

“When I saw patients with cognitive impairment from various brain injuries, particularly stroke, I realized that neurology gets at issues of what makes us unique,” Dromerick says. “Who you are is not in your heart — you can replace that — and you’re still you. The brain is what defines us as human beings.”

The road to rehabilitation

While never steering him strongly in one direction, Dromerick’s parents encouraged their son’s budding interest in science by providing him with books on biology and astronomy. By the time he was a junior in high school, Dromerick was eager to accept a research job at the NIH.

“There was just no looking back by that point,” Dromerick says. “By then, it was pretty clear that the medical route was the one I wanted to take.”

As the next logical step along his journey to medical school, Dromerick attended the University of Virginia where he studied biology and conducted laboratory research under Nobel Prize winner Alfred Gilman M.D., Ph.D.

“The job was actually horrible because I had to go to the slaughter house every three months and collect a few liters of turkey blood from these animals that would later become Thanksgiving dinner,” Dromerick recalls.

Despite the sometimes morbid nature of his work, his position in Gilman’s laboratory was an invaluable experience because it taught him how to analyze problems and develop testable hypotheses. But Dromerick’s academic focus shifted when he began working with patients in medical school at the University of Maryland.

During his neurology fellowship at Cornell University, Dromerick pursued his newfound fascination with clinical neurology by electing to do a rotation in a rehabilitation center, where he cared for people who had experienced brain trauma. There, his experiences as a patient, a clinician and a laboratory scientist converged.

“I had this sort of gut reaction: ‘This is what I want to do,'” Dromerick says. “There are very few ‘ah ha!’ moments in life, but that was one of mine.”

Specializing in neurological rehabilitation allowed him to explore the scientific and philosophical role of the brain while providing him the opportunity to interact with patients and their families because many of them needed continual care.

Because neuro-rehabilitation remains a relatively uncharted field, it offers Dromerick a wide range of research opportunities that can profoundly contribute to the growth of the field.

“It’s a big playground for someone like me,” he says. “I can spin my research in any direction and find important questions that need to be answered.”

Compassionate care

Excited to begin his career in an entirely unfamiliar part of the country, Dromerick eagerly interviewed at Washington University and had another rare ‘ah ha’ moment, immediately realizing this was the place he wanted to be.

Dromerick was thrilled to find both exceptional resources and a welcoming environment upon his arrival in 1994.

As part of the University’s neuroscience, physical therapy and occupational therapy teams, Dromerick has been able to successfully serve his patients through a combination of clinical practice and research, emulating the exceptional standard of patient care he was so grateful to receive when he was a cancer patient.

“He is an excellent team player and facilitator, and he has a great deal of respect for people from all different disciplines, which enables his patients to receive the best care,” says Carolyn M. Baum, Ph.D., professor of occupational therapy and of neurology and a longtime colleague of Dromerick’s. “He is dedicated to bridging the understanding of brain function and rehabilitation interventions to develop the best possible treatments for people with brain injury.”

|

Alexander W. Dromerick Degrees: Bachelor’s, 1980, University of Virginia; doctorate, 1986, University of Maryland University positions: Associate professor of neurology, of occupational therapy and of physical therapy, co-director of the Washington University Stroke Center and medical director of Rehabilitation Services at Barnes-Jewish Hospital Family: Wife, Laurie; stepchildren, Emma, 21, and Michael, 17 Hobbies: Traveling, especially in Europe and to the same beach resort in Nags Head, S.C. He also enjoys cycling, cooking and attending puppy class with their new dog, Aidan. And home brewing — “Beer is more fun to make than cupcakes.” Hometown: Washington, D.C. |

Although he spends a significant amount of time seeing patients at the St. Louis Rehabilitation Hospital and the Barnes Extended Care Clinic, Dromerick describes his primary role as a patient-oriented investigator, who studies the brain and the body and continues to question what makes a person unique.

To that end, Dromerick collaborates with other University researchers as part of the Cognitive Rehabilitation Research Group, funded by the McDonnell Foundation. With Dromerick and Baum as co-principal investigators, this group combines experts in the fields of neurology, radiology, psychology, occupational therapy and physical therapy to investigate how brain injury results in problems with thinking, memory and interacting with the surrounding world.

Dromerick also tests new treatment and rehabilitation approaches for paralyzed individuals and researches ways to improve the quality of life for these patients. For instance, he is testing whether constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) may be more effective than traditional therapy in treating arm weakness caused by stroke.

Traditionally, stroke patients are taught how to compensate for the weakened limb by strengthening the unaffected arm. In contrast, CIMT encourages use of the weak arm by restraining the stronger one in a padded glove for most of the day. By using the weak arm, Dromerick believes patients might be able to re-train the brain to effectively use the limb.

“Dr. Dromerick is a leader in maximizing our reputation as a good place to come for neurological disease,” says William M. Landau, M.D., professor of neurology and former head of the Department of Neurology. “So many of our patients have long-term disabilities, and his critical effort minimizes these disabilities and promotes an improved outcome for the patient.”

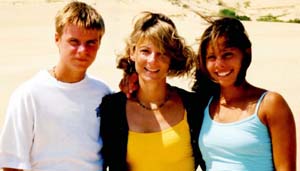

At work, Dromerick’s injured patients help him understand human mental and physical abilities. At home, his new family helps him understand what it’s like to be a kid again.

After working at the Medical Center for nearly five years, Dromerick met his wife, Laurie Dinzebach, then a health-care administrator at BJC. The couple now lives in Webster Groves, Mo., with Laurie’s two children, Emma, 21, and Michael, 17.

“I watch MTV, listen to teenage music and have a different perspective than I might have otherwise,” he says. “It’s a lot of fun to watch the kids grow and evolve as individuals and to know that I’ve had an influence on that.”

As both a parent and a doctor, Dromerick has the privilege of not only watching people thrive as their lives positively progress, but he also has the opportunity to help them when things go wrong.

“Helping patients work through cognitive impairments from various brain injuries allows me the opportunity to get to the core of who we are as people,” he says. “Our brain shapes who we are — it’s what makes us individuals.”