It’s been called “The Last Place on Earth” by National Geographic, and Time describes it as the “Last Eden.”

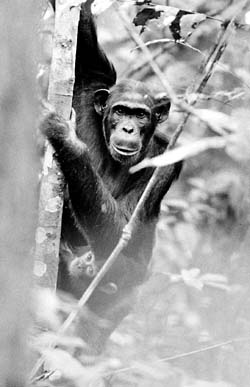

The Goualougo Triangle, nestled between two rivers in a Central African rain forest, is so remote that primate researchers — who traveled 34 miles, mostly by foot, from the nearest village through dense forests and swampland to get there — have discovered a rarity: chimpanzees that have had very little or no contact at all with humans.

The chimpanzees’ behavior when first coming in contact with the researchers was a telltale sign of lack of human exposure — the chimpanzees didn’t run and hide.

Unlike chimpanzees in zoos that seem to appreciate being the center of human attention, chimpanzees in the wild need to be habituated to the presence of humans, a process that can take several years.

Dave Morgan, a field researcher with the Wildlife Conservation Society, Republic of Congo, and Crickette Sanz, a doctoral candidate in anthropology in Arts & Sciences, reported their study of “Naïve Encounters With Chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle” in the April issue of the International Journal of Primatology.

During two field seasons in the Goualougo Triangle (February-December 1999 and June 2000-June 2001), Morgan and Sanz encountered chimpanzees on 218 different occasions, totaling 365 hours of direct observation. Their goal, as with other researchers at various field sites in Africa, was to directly observe the full repertoire of chimpanzee behavior, which includes eating meat, sharing food, grooming, mating and using tools, such as large pounding sticks to break open bee hives and leaf sponges to gather water.

During Morgan and Sanz’s first five minutes observing individual chimpanzees at their field site, curiosity was the most common response the researchers recorded from 84 percent of the chimpanzees. The curious responses from the chimpanzees included staring at the human observers, crouching and moving closer to get a better view of them, slapping tree trunks or throwing branches down to elicit a response, and making inquisitive vocalizations.

“Such an overwhelmingly curious response to the arrival of researchers had never been reported from another chimpanzee study site,” Sanz said. “Researchers have occasionally described encounters with apes who showed curious behaviors toward them. However, these encounters were rare and usually consisted of only a few individuals.”

She said chimpanzees at these other study sites most often fled from human observers during their initial contacts. Those researchers only had glimpses of individual chimpanzees as they rapidly departed.

Researchers have dedicated years at other field sites to habituating wild chimpanzees to human presence so that the chimpanzees regard the humans in their midst as neutral elements not to be feared. Morgan and Sanz often were accepted at first meeting.

“Behaviors such as tool use and relaxed social interactions were only seen after years of patient habituation efforts,” Morgan said of the other field studies, including Jane Goodall’s site in Gombe Stream National Park in East Africa. “Yet these behaviors were sometimes observed during our initial contacts with chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle.

“And many of our initial contacts lasted for more than two hours — some up to seven hours — and ended only when we chose to leave the chimpanzees to continue our surveys. Oftentimes, when we were leaving the chimpanzees, they would follow us through the forest canopy.”

Often the chimpanzees continued to exhibit behaviors indicating their naïveté toward humans after their initial curious responses. Morgan and Sanz define “naïve” contacts as those in which the chimpanzees in a group showed interest in their observers throughout an entire encounter, other chimpanzees joined the group being observed, and they stayed for a relatively prolonged time, with the average encounter lasting 136 minutes. These “naïve” contacts accounted for 69 percent of all chimpanzee encounters.

Other types of encounters occurred, Sanz noted, but much less frequently. Of the 218 encounters, in 12 percent of them, the chimpanzees showed signs of nervousness, including hiding behind vegetation or climbing higher in the canopy; in 11 percent, they departed; and in 8 percent, they ignored the observers.

“The high frequency of curious responses to our arrival and the naïve contacts suggest that the chimpanzees had had little or no contact with humans,” Sanz said. “They certainly had not formed negative associations between human presence and potential threats such as poaching, hunting and habitat destruction.”

A pristine habitat

“During our research presence in the Goualougo Triangle, we’ve never encountered any other humans or even their traces, such as villages, campsites or paths,” Sanz added. “Because of the low human density in northern Congo and the remote location of the Goualougo Triangle, it is unlikely that these chimpanzees had ever encountered humans.”

The study site’s history substantiates this conclusion, Morgan said. People residing in Bomassa, the closest village at 34 miles away, claim that they had not visited the Goualougo Triangle until initial surveys were conducted in 1993 by University alumnus Michael Fay, a conservationist with the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). At the time, Fay, who earned a doctorate in anthropology in 1997, was part of a WCS team documenting the importance of the Goualougo Triangle to conservation and science.

The 100-square-mile Goualougo Triangle is on the southern end of the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park. When the park was created in 1993, the Goualougo Triangle was left out because it was a part of a logging concession.

After discovering this naïve chimpanzee population and their trust in humans — as well as having had naïve contacts with other primate species like gorillas and monkeys that would be vulnerable to poachers and logging — Morgan and Sanz felt an obligation to ensure their long-term protection.

Naïve encounters with the chimpanzees put the Goualougo Triangle at the top of the WCS’ list of priority conservation projects, Morgan said.

The chimpanzees’ unique behavior helped persuade Congolese government officials and the local logging company, which had legal rights to the forest rich in mahogany and other valuable hardwoods, to preserve the pristine habitat.

In July 2001, representatives of the WCS, the Congolese government and the logging company announced that the Goualougo Triangle was to be annexed to the park and its intact ecosystem and undisturbed animal populations would be protected forever.

Goodall visits site

“Dave and Crickette’s work on this chimpanzee population is simply amazing,” said renowned primatologist Robert W. Sussman, Ph.D., professor of anthropology and Sanz’s and Fay’s doctoral adviser. “There is no doubt in my mind that this research will lead to a much better understanding of chimpanzee ecology and behavior and will set the stage for data collection for years to come.

“I also believe that this research may lead to better models of the evolution of human evolution because these chimpanzees are so free from human interference.”

Goodall, considered the world’s foremost authority on chimpanzees, also found Morgan and Sanz’s discovery of a naïve chimpanzee population of such great interest that she visited the site last summer. In nearly 45 years of observing chimpanzees’ behavior in their environment and working to gain their trust, Goodall’s visit to Goualougo Triangle was the first at another study site other than her own in the forests of Gombe Stream National Park.

Goodall was curious to see the naïve chimpanzees that she had heard showed no fear of humans. She also was interested in observing how these chimpanzees differed from those living at Gombe.

Within the past few years, Goodall and other researchers have been comparing chimpanzee behaviors such as tool use and social traditions that are passed on from one individual to another through social learning.

The study of these “chimpanzee cultures” was limited to sites in East and West Africa, Sanz noted, because of political instability and logistical difficulties of setting up long-term field sites in Central Africa.

“Prior to the Goualougo chimpanzee project,” Morgan said, “there were no sites where researchers could conduct direct observations of the behavior and ecology of the central subspecies of chimpanzee residing in the largest tracts of undisturbed forest remaining in equatorial Africa.”

As a result of her visit to the Goualougo Triangle — which National Geographic covered and featured in its April issue — Goodall has extended her conservation efforts into Central Africa. The Jane Goodall Institute recently launched a fund-raising “Campaign to Save the Rainforest of the Congo Basin.”

After her visit to the Goualougo Triangle, Goodall wrote to the National Geographic Society: “This study is of the utmost importance — it is the first such work to be undertaken in a rainforest that has not been exploited by humans, where the chimpanzees, initially, had never seen human beings. Such places are becoming increasingly rare, and the information that has already come out of the research is both fascinating and important.”

“It was such an honor to have Jane Goodall in our camp,” Sanz said. “Our field site is going on four years and her site has been active for that many decades! But as we enter our fourth year in the Goualougo Triangle, we have accomplished a lot within a relatively short research presence, including collecting detailed behavioral data, and beginning to describe the social structure of several communities within the study area.

“Although we will continue to census individual chimpanzees throughout the area,” Sanz added, “we hope to habituate only a few communities in the core of the study area. The other communities will be left to live their lives free from human contact.”

Editor’s note: Photos are courtesy of National Geographic. All rights reserved.