Trinkaus is considered by many to be the world’s most influential scholar of Neandertal biology and evolution. Trinkaus’ research is concerned with the evolution of our genus as a background to recent human diversity. In this, he has focused on the paleoanthropology of late archaic and early modern humans, emphasizing biological reflections of the nature, degree and patterning of the behavioral shifts.

Erik Trinkaus

Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor Emeritus in Arts & Sciences

Contact Information

- Phone: 314-935-5207

- Email: trinkaus@wustl.edu

- Website: Website

Media Contact

In the media

Neanderthals ate dolphins and seals, researchers reveal

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

Neanderthals ‘dived in the ocean’ for shellfish

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

Roughly half of all Neanderthals suffered from ‘swimmer’s ear’

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

Reconstructed Rib Cage Offers Clues to How Neanderthals Breathed and Moved

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

A New Twist to an Extravagant Early-Human Burial Site

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

It turns out Neanderthals painted art inside these European caves, not humans

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

How Neanderthals Made First Glue From Tar To Make Stronger Weapons

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

New Study Fleshes Out the Nutritional Value of Human Meat

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

Cannibalism Study Finds People Are Not That Nutritious

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

400,000-year-old hominin skull fragment hints at ancient ‘unified humanity’

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

Paleo diet revamped? Prehistoric plaque reveals what Neanderthals ate.

Erik Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences

Stories

Older Neandertal survived with a little help from his friends

A young Neandertal left deaf and partially paralyzed by a crippling blow to the head about 40,000 years ago must have relied on the help of others to avoid prey and survive well into his 40s, suggests a new analysis published Oct. 20 in the online journal PLoS ONE.

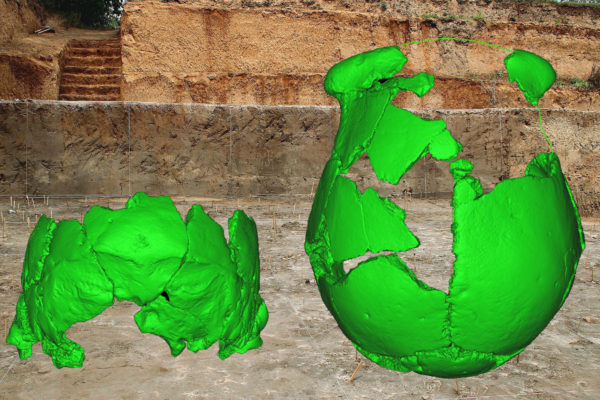

What 100,000-year-old human skulls are teaching us

Two partial archaic human skulls, from the Lingjing site, Xuchang, central China, provide a new window into the biology and populations patterns of the immediate predecessors of modern humans in eastern Eurasia. Securely dated to about 100,000 years ago, the Xuchang fossils present a mosaic of features.

Discovery of Neandertal trait in ancient skull raises new questions about human evolution

Re-examination of a circa 100,000-year-old archaic early human skull found 35 years ago in northern China has revealed the surprising presence of an inner-ear formation long thought to occur only in Neandertals.

Skulls of early humans carry telltale signs of inbreeding, study suggests

Buried for 100,000 years at Xujiayao in the Nihewan Basin of northern China, the recovered skull pieces of an early human exhibit a now-rare congenital deformation that indicates inbreeding might well have been common among our ancestors, new research from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Washington University in St. Louis suggests.

New evidence for the earliest modern humans in Europe

The timing, process and archaeology of the peopling of Europe by early modern humans have been actively debated for more than a century. Reassessment of the anatomy and dating of a fragmentary upper jaw with three teeth from Kent’s Cavern in southern England has shed new light on these issues.

Trinkaus, Yokoyama to receive faculty achievement awards

Erik Trinkaus, PhD, considered by many to be the world’s most influential scholar of Neandertal and early modern human biology and evolution, and Wayne M. Yokoyama, MD, an internationally renowned immunologist and arthritis researcher, will receive Washington University’s 2011 faculty achievement awards, Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton announced.

Longevity unlikely to have aided early modern humans

Life expectancy was probably the same for early modern and late archaic humans and did not factor in the extinction of Neanderthals, suggests a new study by Erik Trinkaus, PhD, professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

30,000-year-old teeth show ongoing human evolution

An international team of researchers, including Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D. professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, has reanalyzed the complete immature dentition of a 30,000 year-old-child from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Portugal. The new analysis of the Lagar Velho child shows that these “early modern humans” were modern without being “fully modern.”

First direct evidence of substantial fish consumption by early modern humans in China

Freshwater fish are an important part of the diet of many peoples around the world, but it has been unclear when fish became an essential part of the year-round diet for early humans. A new study by an international team of researchers, including Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor of Anthropology in Arts & Sciences, shows it may have happened in China as far back as 40,000 years ago.

Late Neandertals and modern human contact in southeastern Iberia

TrinkausNew research published by Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, establishes a late persistence of Neadertals in southwestern Europe some 40,000 years ago. The research sheds light on what were probably the last Neandertals on earth.

Ancient cave bears as omnivorous as modern bears, research suggests

Rather than being gentle giants, new research reveals that Pleistocene cave bears ate both plants and animals and competed for food with the other contemporary large carnivores of the time.Rather than being gentle giants, new research conducted in part by Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, reveals that Pleistocene cave bears ate both plants and animals and competed for food with the other contemporary large carnivores of the time: hyaenas, lions, wolves and our own human ancestors.

Studies affirm relationship between early humans, Neandertals

Joe Angeles/WUSTL PhotoErik Trinkaus, WUSTL professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, holding a Neandertal skull, says the evidence is very convincing that Neandertals and early humans mixed.For nearly a century, anthropologists have been debating the relationship of Neandertals to modern humans. Central to the debate is whether Neandertals contributed directly or indirectly to the ancestry of the early modern humans that succeeded them. As this discussion has intensified in the past decades, it has become the central research focus of Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., professor of anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis. Trinkaus has examined the earliest modern humans in Europe, including specimens in Romania, Czech Republic and France. Those specimens, in Trinkaus’ opinion, have shown obvious Neandertal ancestry.

More human-Neandertal mixing evidence uncovered

Photo courtesy Muzeul Olteniei / Erik TrinkausThe early modern human cranium from the Pestera Muierii, Romania.A re-examination of ancient human bones from Romania reveals more evidence that humans and Neandertals interbred. Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, and colleagues radiocarbon dated and analyzed the shapes of human bones from Romania’s Pestera Muierii (Cave of the Old Woman). The fossils, which were discovered in 1952, add to the small number of early modern human remains from Europe known to be more than 28,000 years old. More…

Modern Humans, not Neandertals, may be evolution’s “odd man out”

Modern Humans may have been the divergent branch.Could it be that in the great evolutionary “family tree,” it is we Modern Humans, not the brow-ridged, large-nosed Neandertals, who are the odd uncle out? New research published in the August, 2006 journal Current Anthropology by Neandertal and early modern human expert, Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, suggests that rather than the standard straight line from chimps to early humans to us with Neandertals off on a side graph, it’s equally valid, perhaps more valid based on the fossil record, that the line should extend from the common ancestor to the Neandertals, and Modern Humans should be the branch off that. More…

Modern Humans, not Neandertals, may be evolution’s ‘odd man out’

Anthropologist Erik Trinkaus argues that “in the broader sweep of human evolution, the more unusual group is not Neandertals, but it’s us — Modern Humans.”

Redating of the latest Neandertals in Europe

TrinkausTwo Neandertal fossils excavated from Vindija Cave in Croatia in 1998, believed to be the last surviving Neandertals, may be 3,000-4,000 years older than originally thought. An international team of researchers, including Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, has redated the two Neandertals from Vindija Cave, the results of which have been published in the Jan. 2-6 early edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Protective footwear nearly 30,000 years old

Erik Trinkaus analyzed anatomical evidence of early modern humans, which suggests a reduction in the strength of the smaller toes.

Protective footwear started nearly 30,000 years ago, research finds

Erik Trinkaus / Czech Academy of SciencesA 26,000 year-old early modern human showing the reduced strength of the bones of the lesser toes.Those high-tech, air-filled, light-as-a-feather sneakers on your feet are a far cry from the leather slabs our ancestors wore for protection and support. But believe it or not, our modern day Nikes and Reeboks are direct descendents of the first supportive footwear that new research suggests came into use in western Eurasia between 26,000 and 30,000 years ago.

Oldest cranial, dental and postcranial fossils of early Modern European humans confirmed

Where have you gone, Joe Neandertal?The human fossil evidence from the Mladec Caves in Moravia, Czech Republic, excavated more than 100 years ago, has been proven for the first time, through modern radiocarbon dating, to be the oldest cranial, dental and postcranial assemblage of early modern humans in Europe. A team of researchers from the Natural History Museum in Vienna, from the University of Vienna in Austria and from Washington University in St. Louis recently conducted the first successful direct dating of the material.

World’s top scholars on modern human origins to gather at Washington University

Some of the world’s top scholars on modern human origins will gather March 26 at Washington University in St. Louis for the last of a four-part series of “Conversations” on key issues that will affect the future of the university, the community and the world. Arts & Sciences is sponsoring the “Conversations,” which are free and open to the public, as part of the university’s 150th anniversary celebration. The “Modern Human Origins” Conversation will be held from 10 to 11:30 a.m. in Graham Chapel.

Earliest modern humans in Europe found

Erik TrinkausA human jawbone (left), dated to between 34,000 and 36,000 years ago, along with a facial skeleton (center) and a temporal bone (right).A research team co-directed by Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., professor of anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis, has dated a human jawbone from a Romanian bear hibernation cave to between 34,000 and 36,000 years ago. That makes it the earliest known modern human fossil in Europe. Other human bones from the same cave — a temporal bone, a facial skeleton and a partial braincase — are still undergoing analysis, but are likely to be the same age. The jawbone was found in February 2002 in Pestera cu Oase — the “Cave with Bones” — located in the southwestern Carpathian Mountains. The other bones were found in June 2003.

Washington University anthropologist sets record straight on Neandertal facial length

Erik Trinkaus, professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, examines a Neandertal skull.New scientific evidence challenges a common perception that Neandertals — a close evolutionary relative to modern humans that lived 230,000 to 30,000 years ago — possessed exceptionally long faces. Instead, a report authored by Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, shows that modern humans are really the “odd man out” when it comes to facial lengths, which drop off dramatically compared with their ancestral predecessors.