March 15th will mark the third anniversary of a law passed by the French government banning from public schools all clothing that indicates a student’s religious affiliation. Though written in a religion-neutral way, most people in France, and around the world, knew the law was aimed at keeping Muslim girls from wearing headscarves to class.

But why?

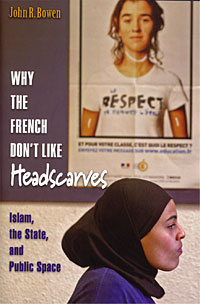

John R. Bowen, Ph.D., the Dunbar-Van Cleve Professor of Sociocultural Anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, was in France at the time and has written an enlightening book, recently published by Princeton University Press, titled “Why the French Don’t Like Headscarves: Islam, the State and Public Space.”

In it, he attempts to explain through an examination of France’s religious history, ideas about politics and society, and day-to-day media coverage and political events leading up to the law in 2003-04 why the French government made such a perplexing move.

“French public figures seemed to blame the headscarves for a surprising range of France’s problems,” writes Bowen in the book’s introduction, “including anti-Semitism, Islamic fundamentalism, growing ghettoization in the poor suburbs, and the breakdown of order in the classroom. A vote against headscarves would, we heard, support women battling for freedom in Afghanistan, schoolteachers trying to teach history in Lyon, and all those who wished to reinforce the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity.”

Bowen, an expert on religion, politics and Islam, was in France conducting research on what Muslims were doing to create their own schools and other institutions in the country.

He says that Muslims living in non-majority Muslim countries like France find it challenging to adapt their religious institutions and practices — such as the wearing of headscarves by Muslim women and girls — to secular laws and traditions.

From that research, he’s working on another book, titled “Shaping Islam in France,” to be published in 2008, which will examine how French Muslims strive to build a base for their religious lives in a society that views these practices as incompatible with national values.

But as the debate over headscarves heated up, he became interested in that subject and began to follow it closely.

“It’s an odd enough thing to do, to ban headscarves,” he says. “It led to so much international perplexity or anger that is was worth writing about. Also, it tapped into something deep about France and about people who don’t fit into the French cultural mode.”

Bird’s eye view

Living in France provided Bowen an unusual opportunity to see first-hand how the passage of the headscarves ban unfolded. Bowen sat through debates on the topic at the National Assembly, he analyzed newspapers and television programs and he talked to many officials and intellectuals involved in these issues, both Muslims and non-Muslims.

In the book, Bowen examines the long-term nature of how the state relates to religion in France. He looks at the relationship of external events in the Islamic world and French concerns about Islam, starting in the 1980s. He then examines the 10-month period preceding the law banning headscarves to explain in a much more day-to-day way how public opinion was turned against headscarves and how political pressure to “do something” took over the country.

“France has a long-standing tradition of state control and support of religious activity despite its modern laws concerning secularity,” says Bowen. “We often have the misconception that the state stays out of religious affairs. In fact, the French government pays the salaries of all teachers in private religious schools, it organized a national Islamic body, and it and city governments put a lot of money into building churches and mosques.

“But because the Republican political tradition that developed out of the French Revolution of 1789 targeted the privileges of the Catholic Church, many French citizens developed a certain allergy to religions’ symbolism in public, and particularly in schools, a battleground between the Church and the Republic,” continues Bowen.

“French people see schools as a place where children should leave their particular religious, ethnic or regional loyalties behind and just enter into French life. It’s different from our notion of local control.”

Rising tension

France has been involved in a tense relationship with the Islamic world since the late 1980s, says Bowen. Algeria, which is now a Muslim state, was part of France until it became independent in 1962.

In the 1980s, with the rise of the political Islam of Salman Rushdie and the Ayatollah Khomeini, many younger French people began claiming the right to be Muslim in public with beards and headscarves.

Also around that time, there began to be bombings in France by people associated with an Islamic military movement in Algeria.

“French people started to link what they saw as dangerous or violent Islam elsewhere in the world with what they saw happening in France,” says Bowen. “Every time there was a rise in concern about that, there was a rise in pressure to keep headscarves out of schools. When fear of Islam in the world died down, then that pressure receded as well.”

However, in the spring of 2003, France’s Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy, a front-runner to be his country’s next president, made a famous speech denouncing Muslims who did not follow a French law requiring the removal of head coverings for identity photos. He drew a link between Muslim women wearing a headscarf and the failure of Muslims to embrace the Republic.

According to Bowen, the speech fueled a political and media bandwagon; eventually public opinion turned from not wanting to ban headscarves in schools because it seemed trivial to being massively in favor of the law.

The law was passed on March 15, 2004, and first went into effect in September 2004.

“People were prepared for a lot of tension and many girls said they were going to try to wear the scarves anyway,” Bowen says. “Then there were some French reporters taken hostage by an armed Islamic group in Iraq that demanded that France rescind the law. Although the two journalists were eventually freed, the fact that they were taken hostage made it disloyal in the court of public opinion to be against the law and many opponents backed off. That was it. There have been very few incidents and things quieted down very quickly.”

In fact, the major effect of the law’s passage has been to build support for a private school sector that is under development for Muslims in France, Bowen says.

“Muslim public leaders have been creating schools, institutes of higher learning and other training centers to improve Muslims’ futures,” he says. Bowen has been following one school, which is likely to be the first to receive state funding. There, teachers follow the national curriculum, but they and the students can wear headscarves and pray together on Fridays, just as Catholics follow Catholic worship in their own schools.