Researchers long have known that some portion of the risk of developing cancer is hereditary and that inherited genetic errors are very important in some tumors but much less so in others. In a new analysis, researchers have shed light on these hereditary elements across 12 cancer types — showing a surprising inherited component to stomach cancer and providing some needed clarity on the consequences of certain types of mutations in well-known breast cancer susceptibility genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2.

The study, from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, appears Dec. 22 in the journal Nature Communications.

The investigators analyzed genetic information from more than 4,000 cancer cases included in The Cancer Genome Atlas project, an initiative funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to unravel the genetic basis of cancer.

“In general, we have known that ovarian and breast cancers have a significant inherited component, and others, such as acute myeloid leukemia and lung cancer, have a much smaller inherited genetic contribution,” said senior author Li Ding, PhD, associate professor of medicine and assistant director of the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University. “But this is the first time on a large scale that we’ve been able to pinpoint gene culprits or even the actual mutations responsible for cancer susceptibility.”

The new information has implications for improving the accuracy of existing genetic tests for cancer risk and eventually expanding the available tests to include a wider variety of tumors.

Past genomic studies of cancer compared sequencing data from patients’ healthy tissue and the same patients’ tumors. These studies uncovered mutations present in the tumors, helping researchers identify important genes that likely play roles in cancer. But this type of analysis can’t distinguish between inherited mutations present at birth and mutations acquired over the lifespan.

To help tease out cancer’s inherited components, the new study adds analysis of the sequencing data from the patients’ normal cells that contain the “germline” information. A patient’s germline is the genetic information inherited from both parents. This new layer of information gives a genetic baseline of a patient’s genes at birth and can reveal whether cancer-associated mutations were already present.

In all the cancer cases they analyzed, the investigators looked for rare germline mutations in genes known to be associated with cancer. If one copy of one of these genes from one parent is already mutated at birth, the second normal copy from the other parent often can compensate for the defect. But individuals with such mutations are more susceptible to a so-called “second hit.” As they age, they are at higher risk of developing mutations in the remaining normal copy of the gene.

“We looked for germline mutations in the tumor,” Ding said. “But it was not enough for the mutations simply to be present; they needed to be enriched in the tumor — present at higher frequency. If a mutation is present in the germline and amplified in the tumor, there is a high likelihood it is playing a role in the cancer.”

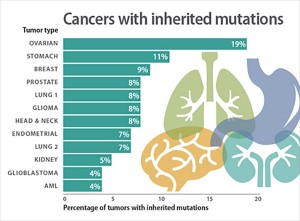

In 114 genes known to be associated with cancer, they found rare germline mutations in all 12 cancer types, but in varying frequencies depending on the type. They focused on a type of mutation called a truncation because most truncated genes can’t function at all.

Of the ovarian cancer cases the investigators studied, 19 percent of them carried rare germline truncations. In contrast, only 4 percent of the acute myeloid leukemia cases in the analysis carried these truncations in the germline. They also found that 11 percent of the stomach cancer cases included such germline truncations, which was a surprise, according to the researchers, because that number is on par with the percentage for breast cancer.

“We also found a significant number of germline truncations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes present in tumor types other than breast cancer, including stomach and prostate cancers, for example,” Ding said. “This suggests we should pay attention to the potential involvement of these two genes in other cancer types.”

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are important for DNA repair. While they are primarily associated with risk of breast cancer, this analysis supports the growing body of evidence that they have a broader impact.

“Of the patients with BRCA1 truncations in the germline, 90 percent have this BRCA1 truncation enriched in the tumor, regardless of cancer type,” Ding said.

Genetic testing of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in women at risk of breast cancer can reveal extremely useful information for prevention. When, for example, the genes are shown to be normal, there is no elevated genetic risk of breast cancer. But if either of these genes is mutated in ways that are known to disable either gene, breast cancer risk is dramatically increased. In this situation, doctors and genetic counselors can help women navigate the options available for reducing that risk.

But mutations come in a number of varieties. Genetic testing also can reveal many that have unknown consequences for the function of these genes, so their influence on cancer risk can’t be predicted.

To help clarify this gray area in clinical practice, Ding and her colleagues Jeffrey Parvin, MD, PhD, professor and director of the division of computational biology and bioinformatics at The Ohio State University, and Feng Chen, PhD, associate professor of medicine at Washington University, investigated 68 germline non-truncation mutations of unknown significance in the BRCA1 gene. For each mutation, they tested how well the BRCA1 protein could perform one of its key DNA-repair functions. The researchers found that six of the mutations behaved like truncations, disabling the gene completely. These mutations also were enriched in the tumors, supporting a likely role in cancer.

“It is important to be able to show that these six mutations of unknown clinical significance are, in fact, loss-of-function mutations,” Ding said. “But I also want to emphasize the contrasting point. Many more show normal function, at least according to our analysis. Many of these types of mutations are neutral, and we would like to identify them so that health-care providers can better counsel their patients.”

Ding said more research is needed to confirm these results before they can be used to advise patients making health-care decisions.

“Our strategy of investigating germline-tumor interactions provides a good way to prioritize important mutations that we should focus on,” she said. “For the information to eventually be used in the clinic, we will need to perform this type of analysis on even larger numbers of patients.”

Other key contributors to the study include Charles Lu, PhD; Mingchao Xie; Mike Wendl, PhD; Mike McLellan; Jiayin Wang, PhD; and Kim Johnson, PhD, from Washington University; and Mark Lerseison from Brown University.