While Pope Francis’ whirlwind tour of the United States might seem like a politicized poke-in-the-eye to some conservative American Catholics, his itinerary and social justice talking points closely mirror core Catholic beliefs detailed in church scripture since Matthew wrote his gospel, suggests a historian of Christianity at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Pope Francis’ stance on controversial modern issues, such as climate change, poverty, immigration and the prison system, reflects teachings at the very core of the Catholic Church,” said Daniel E. Bornstein, PhD, the Stella K. Darrow Professor of Catholic Studies at Washington University.

“Those who criticize him for being too progressive, or even a left-leaning socialist, are forgetting that the social justice principles he preaches are firmly based in a longstanding Catholic tradition known as ‘works of mercy,’ ” Bornstein said. “’If anything, his stance on many modern issues reflects a return to simple teachings that have guided the Catholic Church for centuries.”

As Bornstein notes, the Catholic tradition of “works of mercy” is derived from the description of the Last Judgment in the Gospel of Matthew, Chapter 25, in which those who have treated others well during their lives on earth are welcomed into heaven with the words, “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.”

“References to this scriptural passage have been surprisingly absent from public discourse on religion in the public arena, which has tended to focus on sexual ethics and reproductive matters to the neglect of broader questions of charity, mercy, and social justice,” Bornstein said. “Conservative, church-going Catholics might quibble over the Pope’s stance on controversial American policy issues, such as immigration, but how can you turn your back on Syrian refugees if you truly believe that God commands us to welcome the stranger as if he were Jesus himself?”

Bornstein, who has closely studied the evolution of Catholic practices, said it’s easy to see why the works of mercy have a special place in the heart of Pope Francis, given that the Pope’s early work in the church focused on serving the poor and needy in the slums of Argentina.

As in modern slums, many early Christian followers eked out a precarious existence in a world filled with day-to-day economic and social challenges. Works of mercy became a core component of the Catholic tradition, said Bornstein, because the very survival of early Christian communities often hinged on the willingness of each to help others through tough times.

And while many have overlooked the connection, Pope Francis has made clear that his current agenda is driven by a strong desire to renew the church’s emphasis on works of mercy.

Declaring that “Mercy is the very foundation of the Church’s life,” the Pope issued a letter in April of this year announcing that the church would launch a special Holy Year celebration on Dec. 8 with the specific goal of encouraging the faithful to reflect on the corporal and spiritual works of mercy.

“Let us rediscover these corporal works of mercy: to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, welcome the stranger, heal the sick, visit the imprisoned, and bury the dead,” the Pope wrote. “And let us not forget the spiritual works of mercy: to counsel the doubtful, instruct the ignorant, admonish sinners, comfort the afflicted, forgive offences, bear patiently those who do us ill, and pray for the living and the dead.”

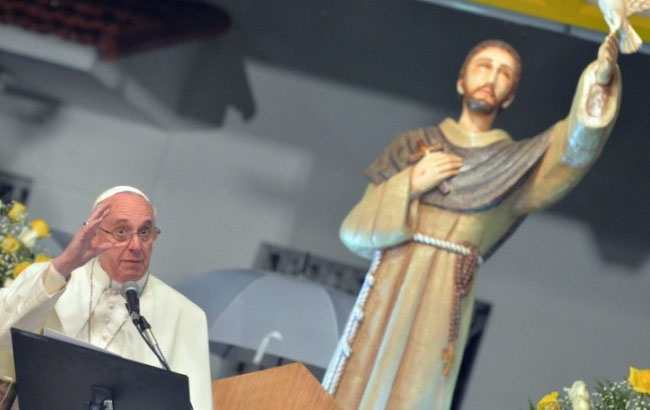

While the spiritual and corporal works of mercy may seem like the perfect prescription for many modern woes, applying them to real-world challenges outside church walls has always been a challenging proposition, said Bornstein, but in placing them at the center of his apostolate Pope Francis is living up to the example set by his namesake, St. Francis of Assisi.

St. Francis embraced a life of absolute poverty, renouncing all earthly goods. But he embraced more than the principle of apostolic poverty. He also embraced the poor, the sick, the outcasts of society.

When Francis reflected on his spiritual journey, Bornstein said, he pointed to his encounter with a leper as a transformative moment. “While I was in sin,” St. Francis recalled, “it seemed very bitter to me to see lepers. And the Lord Himself led me among them and I had mercy upon them. And when I left them that which seemed bitter to me was changed into sweetness of soul and body.”

Although Pope Francis is a Jesuit by training, it is this Franciscan spirit of simplicity and humility that defines his manner, Bornstein said. The Franciscan love for the world as God’s creation inspires his ecological vision, as he made clear when he opened his encyclical on care for the planet, “Laudato si’,” by invoking St. Francis’ hymn of praise for Brother Sun, Sister Moon, and Mother Earth.

And it is the Franciscan embrace of poverty and the poor that drives Pope Francis’ insistence that we not only care for the poor, but treat them with honor and respect.