New research may help explain why drug treatments for addiction and depression don’t work for some patients.

The conditions are linked to reward and aversion responses in the brain. Working in mice, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered brain pathways linked to reward and aversion behaviors are in such close proximity that they unintentionally could be

activated at the same time.

The findings suggest that drug treatments for addiction and depression simultaneously may stimulate reward and aversion responses, resulting in a net effect of zero in some patients.

The research is published online Sept. 2 in the journal Neuron.

“We studied the neurons that cause activation of kappa opioid receptors, which are involved in every kind of addiction — alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine,” said principal investigator Michael R. Bruchas, PhD, associate professor of anesthesiology and neurobiology. “We produced opposite reward and aversion behaviors by activating neuronal populations located very near one another. This might help explain why drug treatments for addiction don’t always work — they could be working in these two regions at the same time and canceling out any effects.”

Addiction can result when a drug temporarily produces a reward response in the brain that, once it wears off, prompts an aversion response that creates an urge for more drugs.

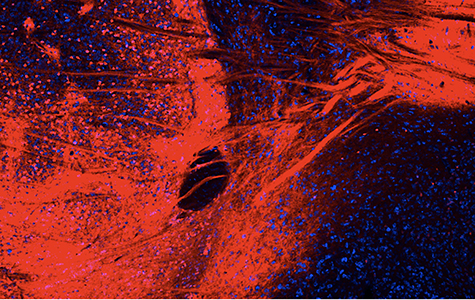

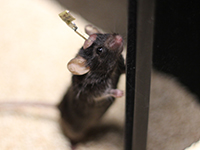

The researchers studied mice genetically engineered so that some of their brain cells could be activated with light. Using tiny, implantable LED devices to shine a light on the neurons, they stimulated cells in a region of the brain called the nucleus accumbens, producing a reward response. Cells in that part of the bran are dotted with kappa opioid receptors, which are involved in addiction and depression.

The mice returned over and over again to the same part of a maze when the researchers stimulated the brain cells to produce a reward response. But activating cells a millimeter away resulted in robust aversion behavior, causing the mice to avoid these areas.

“We were surprised to see that activation of the same types of receptors on the same types of cells in the same region of the brain could cause different responses,” said first author Ream Al-Hasani, PhD, an instructor in anesthesiology. “By understanding how these receptors work, we may be able to more specifically target drug therapies to treat conditions linked to reward and aversion responses, such as addiction or depression.”

Funding for this research comes from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers P30 NS057105,

R01 DA033396, R01 DA037152 K99/R00 DA038725, TR01 NS081707 R01 DK075623, R37 DK053477, R01 DK089044, R01 DK071051, R01 DK096010, P30DK046200 and P30 DK057521.

Al-Hasani R, McCall JG, Shin G, Gomez AM, Schmitz GP, Bernardi JM, Pyo CO, Park SI Marcinkiewcz CM, Crowley NA, Krashes MJ, Lowell BB, Kash TL, Rogers JA, Bruchas MR. Distinct subpopulations of nucleus accumbens dynorphin neurons drive aversion and reward. Neuron, published online Sept. 2, 2015.