War looks different, before you’re in it.

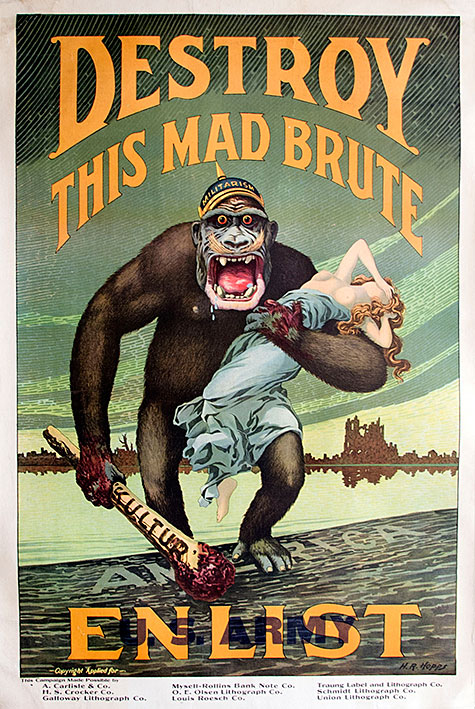

In 1914, as Europe lumbered optimistically to battle, a proxy fight was joined in the pages of popular media. Combatant nations, seeking cultural as well as military dominance, deployed visual propaganda to rally support and attack enemies. Yet as the death toll mounted, a generation of artists, many of whom served in uniform, sought new artistic languages to convey the grief and horror they had witnessed.

This fall, the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis will present “World War I: War of Images, Images of War.” Drawn primarily from the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, where it debuted in fall 2014, the exhibition features more than 150 objects that together chart a chronological path from exuberant outbreak through years of grinding combat and into the long, unsettled aftermath.

Included are paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, illustrated journals, correspondence from the front and other materials by artists such as Max Beckmann, Umberto Boccioni, Georges Braque, Otto Dix, Natalia Goncharova, George Grosz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Käthe Kollwitz, Fernand Léger and Kazimir Malevich.

The exhibition opens with “War of Images,” which explores how different nations sought to elevate their own cultural symbols while denigrating the supposed national traits — German barbarism, British imperialism, French decadence, Russian cowardice — of opponents.

French artist Jean Cocteau, whose health prevented enlistment but who later drove a Red Cross ambulance, co-founded the journal Le Mot (“The Word”) with designer Paul Iribe. The cover of their second issue depicts Kaiser Wilhelm II as the German hero Lohengrin, but wittily replaces the knight’s legendary swan boat with a red, grasping crayfish.

Conversely, the German magazine Simplicissimus, a longtime government critic, now voiced patriotic support. A striking cover from October 1914 — by Thomas Theodor Heine, who’d once been jailed for caricaturing the Kaiser — shows a colonial Englishman, pith helmet ajar, clutching precariously at a blood-soaked globe.

Other works play on visual codes such as the Russian bear and the French Marianne. A series of rarely seen images by avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich and poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, modeled on popular Russian prints known as lubki, depict idealized peasants in traditional costume fearlessly routing enemy troops.

Images of War

But for witnesses on the ground, arguments about cultural superiority quickly paled. “Images of War,” the exhibition’s second section, collects artworks, letters, diaries and other first-person accounts that demonstrate the yawning gap between rhetoric and the reality of battle.

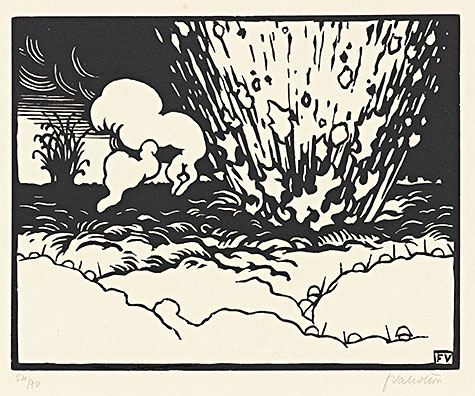

Symbolist Henry de Groux, who fled Belgium just ahead of German invasion, captures the air of menace with his dark and swirling “Grenade Thrower,” from the series “Le visage de la victoire” (1914-16). In “The Trench” (1915-16), Swiss-born artist Félix Vallotton depicts a line of French soldiers, only helmets and bayonets visible, as the earth explodes behind them.

A never-before-exhibited war diary by futurist Umberto Boccioni, who died in 1916, details a tumultuous period on the Italian front. The expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, who was deeply scarred by his time in the German Army — and whom, decades later, the Nazis would brand a “degenerate artist” — drew the Apocalypse on the backs of cigarette boxes.

Also included are rare examples of handmade “trench art,” with which soldiers memorialized their units and the battles they fought. These range from painted helmets and an engraved canteen to small objects made from shell casings.

Aftermath

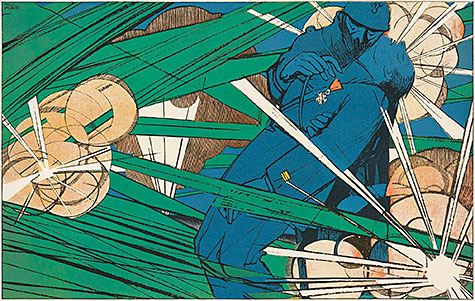

The final section, “Aftermath,” opens with celebrations of armistice and photographs of jubilant French crowds. Yet even for Allies, victory was pyrrhic. Fernand Léger, who barely survived mustard gas, fills his illustrations for Blaise Cendrars’ “J’ai tué” (“I Have Killed”) (1918) with rifles, helmets and fractured war matériel.

The Germans Max Beckmann, Otto Dix and George Grosz spent years coming to terms with their experiences, with Dix in particular returning obsessively to the subject. In addition to several prints, the exhibition features recordings, made in 1963, in which Dix discusses his time as a machine-gunner on the Western front.

But the costs of combat are not paid by soldiers alone. Käthe Kollwitz’s son, Peter, was a student in Berlin when fighting began. He quickly enlisted and died in Flanders — the first of his regiment to fall. A decade later, the grieving mother completed “Seven Woodcuts about the War” (1924), a searing testament to the anguish of those left behind. As Kollwitz would write to one of Peter’s comrades, himself later killed at Verdun:

“There is in our lives a wound which will never heal. Nor should it.”

“World War I: War of Images, Images of War” is organized by the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. Works are drawn primarily from the Getty archives, with loans from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Washington University’s Modern Graphic History Library; and private collections.

The St. Louis iteration features additional works from the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Kemper Art Museum and local private collections. It is curated by Karen K. Butler, associate curator of the Kemper Art Museum.

An opening reception will take place at 7 p.m. Friday, Sept. 11. The exhibition will remain on view through Jan. 4, 2016.

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

The Kemper Art Museum is located on Washington University’s Danforth Campus, near the intersection of Skinker and Forsyth boulevards. Regular hours are 11 a.m.-5 p.m. daily except Tuesdays and 11 a.m.-8 p.m. the first Friday of the month. The museum is closed Tuesdays.

Support for the exhibition is provided by the William T. Kemper Foundation, the Hortense Lewin Art Fund, the Yeatman Fund, and members of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum.

For more information, call 314-935-4523, visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu or follow the museum on Facebook and Twitter.