Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns

driven time and again off course, once he had plundered

the hallowed heights of Troy.

-The Odyssey of Homer (translated by Robert Fagles)

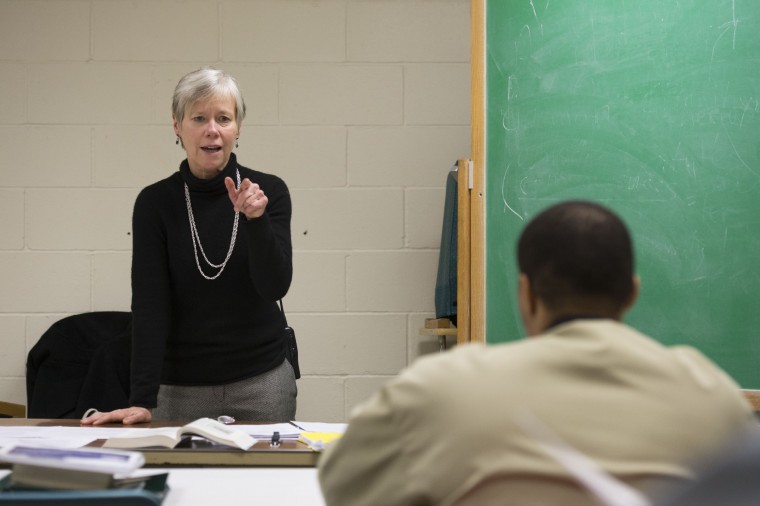

It is 10 a.m. on a Wednesday morning, and Robert Henke is leading 15 students through “Text and Tradition,” a 200-level survey course on classical and Renaissance literature.

Henke, PhD, professor of drama and of comparative literature in Arts & Sciences, has taught at Washington University in St. Louis for more than two decades. But this particular section meets at an unusual location — 30 miles southwest of campus, at the Missouri Eastern Correctional Center in Pacific, Missouri.

“This is some of the most worthwhile teaching I’ve ever done,” Henke said. “It’s exactly the same course that I teach at WashU. Same syllabus, same rating, same requirements. The students read everything very carefully and know the texts really well. You ask a question, six hands go up.”

Last fall, a handful of Washington University faculty — including Henke and Margaret Garb, PhD, associate professor of history in Arts & Sciences — launched the Washington University Prison Education Project, a three-year pilot program at Pacific, as the medium-security institution is commonly known.

‘This program represents hope.’

Warden Jennifer Sachse

Presented under the auspices of University College, the professional and continuing education division of Arts & Sciences, the program is supported by a grant from the Bard Prison Initiative, through its Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison.

“This is a great example of the transformative power of higher education,” said Barbara A. Schaal, PhD, dean of the faculty of Arts & Sciences and the Mary-Dell Chilton Professor. “The majority of these prisoners will eventually be released, and programs like this help prepare them for that day.

“As an educational institution, we also have a duty to challenge them,” Schaal said. “This is a rigorous program, held to high academic standards. The work is valuable, enlightening and enriching — but it is not easy.”

Though the Prison Education Project began with just two classes, the group’s executive committee has recruited three additional Arts & Sciences faculty to teach in the spring.

Barbara Baumgartner, PhD, senior lecturer in women, gender and sexuality studies, is teaching “American Literature to 1865.” Claude Evans, PhD, professor of philosophy, is teaching “Introduction to Philosophy.” And Leonard Green, PhD, professor of psychology, is teaching a class for prison staff, “Introduction to Psychology.”

Eventually, organizers hope to offer enough classes that participants will be able to earn associate’s degrees.

“That’s the ambition,” said Robert Wiltenburg, PhD, dean of University College. “It’s still a startup year, but everyone is taking this opportunity very seriously. The faculty are very dedicated, and the students are very committed to the idea of remaking and rebuilding their lives.”

Certain kinds of skills

According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, between 1970 and 2005, the U.S. prison population grew approximately 700 percent. Today, almost 1 percent of U.S. adults are behind bars. And though studies consistently find that higher education can reduce recidivism rates by as much as half, only a small fraction of prisoners have access to such programs.

“We have a problem in America with mass incarceration,” said Garb, who teaches the history survey “Freedom, Citizenship, and the Making of American Culture.” “Enormous numbers of people are essentially thrown away. It’s a problem we all need to take seriously.

“Every now and then I volunteer at the food bank,” Garb said. “It’s good, I’m happy to do it. But as a teacher, I’ve spent years training and gaining certain kinds of skills. It seemed worthwhile to think about how to use those skills most effectively to improve the society we live in.”

‘This is some of the most worthwhile teaching I’ve ever done.’

Robert Henke

For the first semester, Henke and Garb received 65 applications, from which they were able to choose 30 students. Participants — who must have a high school diploma or GED — filled out a standard University College application and wrote a pair of essays, describing why they want to be part of the program as well as a book, person or film that has influenced them.

“This program represents hope,” said Warden Jennifer Sachse. “It provides an opportunity for those who have made bad choices to make a positive change. It demonstrates to the offenders that they can accomplish goals and be successful.

“The look on their faces while they are in class says it all,” Sachse said. “It is as if they are on campus. We are truly appreciative to Washington University and their staff for partnering with us. We are changing lives.”

Said Garb: “A liberal arts education helps you see the world differently. It helps you to understand your relationships with other people differently. And transforming one person — whether it’s a student on a college campus or someone in prison — also transforms their family and community.

“It has a profound effect.”

Odysseus in Pacific

Henke first visited Pacific as a volunteer with Prison Performing Arts. The nationally known program — which was founded in 1989 by Agnes Wilcox, a veteran theater director and longtime lecturer in the Performing Arts Department in Arts & Sciences — enables incarcerated youth and adults to stage classic and contemporary plays.

“We had great, substantive discussions about Hamlet and 19th-century Russian satire,” Henke said. “The guys were really interesting and engaged. But teaching a full class is even more rewarding because I see the same students week after week. They’re really serious about it.”

‘As a teacher, I’ve spent years training and gaining certain kinds of skills. It seemed worthwhile to think about how to use those skills most effectively to improve the society we live in.’

Margaret Garb

Henke said that that Prison Education Project would not exist without the support of Sachse, Brenda Short, deputy warden, and George Lombardi, director of the Missouri Department of Corrections. But ultimately, its success rests on the shoulders of the students themselves.

“I’ve taught ‘The Odyssey’ many times, but I’ve never had a group better understand just how completely bereft Odysseus becomes,” Henke said. “He loses everything — his fleet, his men, his possessions, his identity. When the Cyclops asks his name, he says, ‘I’m Nobody.’

“It’s not that the guys are explicitly saying ‘That’s like me,’” Henke said. “But they’re a little older than most undergraduates, and they have a lot of life experience. They understand what it means to lose your role in the community. And they will be experiencing their own homecomings — the great theme of Homer’s poem — very soon.

“There’s a great moment of recognition between Odysseus and his son, Telemachus,” Henke said. “Telemachus says, ‘You must be a god. I don’t believe you’re Odysseus.’ And Odysseus says ‘I’m not a god, I’m your father.’

“It suddenly got pretty still in the classroom.”