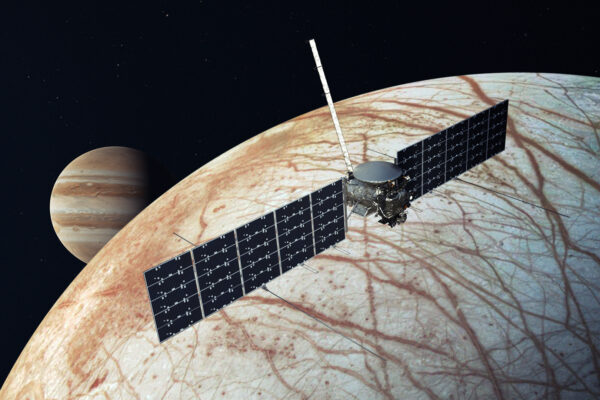

It’s an exciting time to be a lunar scientist, like WashU’s Emily Culley. With its Artemis campaign, NASA is charting a new course to explore the moon for scientific discovery, technology advancement and to learn how to live and work on another world as we prepare for human missions to Mars.

Culley, a PhD candidate in earth, environmental and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences, uses images from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera to investigate the surface of the moon, helping to improve our understanding of lunar geology and formation.

Originally from Pittsburgh, Culley worked as a WashU peer mentor coordinator for her department and is passionate about fostering an inclusive environment in the sciences. Here, Culley shares her thoughts on how leaders can help create a welcoming community.

How did you become interested in science?

You might say that the family business is teaching. My dad is a professor. My mom taught and tutored elementary math and reading. My grandma taught physics and calculus, and my grandfather was an adjunct professor. Growing up, everyone in my house really liked learning.

My father does research in the social sciences, so we did analytical experiments at home for fun! When I was little, 3 or 4 years old, we kept a bar graph on the fridge to track how many sections there were in a clementine. Every time we peeled one, we filled in boxes on the chart. I remember counting and talking about simplified math, averages and variability concepts. My desire to learn and think about the world in an inquisitive fashion is because of my dad and mom.

You were highly involved with WashU’s peer mentoring program. How did you foster graduate student camaraderie and support?

It was our job to partner incoming first-year grad students with student mentors. I started during preview weekend, when I met prospective students and tried to remember their personalities. I also sent out a questionnaire based on things that I had learned were informative when I tutored high school students. Finding out what someone’s most and least favorite subjects are actually tells you a lot about how their brains work best. That insight helped us match new students and mentors.

We also found that second-year students preparing for their oral exams still need a lot of support, so we expanded the program. We arranged practice talks and office hours where students could come ask questions, and we kept a study hall open for practice. We found that even first-years benefited from this, mostly by having opportunities to make friends.

We also worked to bolster the longstanding tradition of a first-year party, which was less academic but fun and beneficial. Our goal is to foster an environment where new grad students can get to know others.

Finding someone who you have a rapport with can make a really big difference later when they, or you, need advice. If you don’t feel comfortable talking with your professor — because it’s a simple question, or because you’re embarrassed, or because you’re busy — it’s important to have someone familiar to turn to.

How do you make sure that everyone can see a place where they belong in the sciences?

That’s a good question. Some people would say social media is a good place to start. I’ve heard people talk about making your science accessible by being funny on your platform and sharing your science. Some people in our field and in our department are really good at that.

Another important way to build our community is to just talk to people that we don’t know. For example, at conferences, you can seek out people that you haven’t talked to, particularly undergrad or early-career researchers. Learn about their science and background. Treat them with respect. Because we all deserve to be growing in the field.