Research from the Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis helps explain why President Donald Trump’s 2018 tariffs did not accelerate investment in domestic manufacturing and serves as a warning for how the current wave of tariffs may impact U.S. production going forward.

In their 2024 paper, “Flexibility Value of Reshoring Capacity under Policy Uncertainty and Domestic Competition,” Panos Kouvelis, the Emerson Distinguished Professor of Supply Chain, Operations and Technology and director of the Boeing Center for Supply Chain Innovation at WashU, and co-authors Xiao Tan and Sammi Tang, examine how supply chain managers at global companies weigh decisions to reshore manufacturing when faced with costly tariffs.

Traditionally, governments have used tariffs — a tax on imported goods — to encourage domestic production or exert political leverage over another country. However, Trump’s 2018 tariffs, which were largely maintained by the Biden administration, did not accelerate investment in domestic manufacturing and had a negative effect on U.S. manufacturing jobs overall.

According to Kouvelis, these managerial decisions are not as straightforward as one might think. The product level and supply chain stage at which these tariffs are imposed makes a significant difference on their effectiveness in driving reshoring decisions, he said.

“Tariffs imposed at raw material and/or component level — such as on steel, aluminum, silicon, ingots, etc. — have detrimental effects on reshoring investments,” he said. “Tariffs increase the costs of any manufacturer — global or domestic — when using the raw materials and/or components in producing finished goods for the local market.

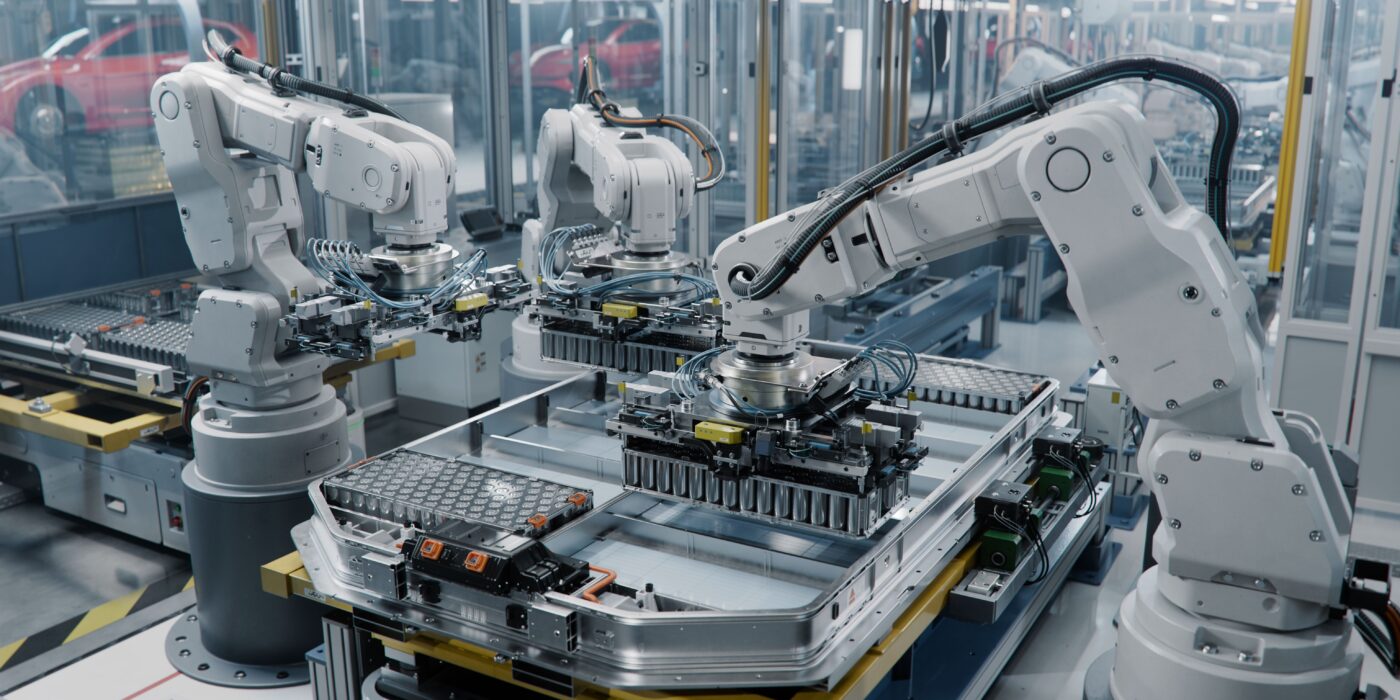

“This is especially true for industries like solar panels and electric vehicles (EVs) that are lacking strong domestic supply chains in upstream components, including ingots and wafers for solar panels, and batteries for EVs. Similarly, there is a slowdown in reshoring for U.S. bicycle manufacturers due to increased component-level tariffs.”

Indeed, a 2023 report by the United States International Trade Commission confirms that the section 232 tariffs on imported steel and aluminum negatively affected downstream industries that depend on these materials, Kouvelis said.

At the finished-goods level, the downstream stage that sells directly to the end-consumers, tariffs have a more ambiguous impact on managers’ decision-making. In the paper, the authors explain these two opposing effects:

- Decreased planned output effect: When the higher cost of imported finished goods increases the average cost of serving the market and reduces the capacity needs, managers may ultimately decrease reshoring capacity investment.

- Costlier overflow demand effect due to tariffs: When strong local demand exceeds the conservative reshoring capacity investment — mostly due to demand and policy uncertainties — and overflow to offshore facilities would be costly, managers may be motivated to increase reshoring capacity investments.

“A finished-good tariff can lead to an increased or decreased reshoring capacity depending on which of the above effects is the dominant one,” Kouvelis explained. “When the overflow demand effect dominates, reshoring investments increase. We have seen strong such investments in North America — but mostly in Mexico — for vehicle manufacturing, batteries and other clean-energy industries.”

The impact of tax credits

In the same research paper, Kouvelis and his co-authors studied the impact of tax credit policies that subsidize buying certain products based on domestic supply content and assembly requirements. For example, EV manufacturers using U.S.-sourced battery minerals, and with battery components manufactured and final assembled in the U.S., qualify for a $7,500 tax credit that is offered to consumers purchasing their cars. Another example is a tax credit for solar panel installations with local assembly requirements.

The research argues that tax credits are an effective tool to increase reshoring investments. In recent reported studies, global corporations — including U.S., Chinese, Singaporean and South Korean — announced more than 50 domestic solar manufacturing facilities in response to tax subsidies, Kouvelis said.

“For global firms, investing in reshoring capacity creates a ‘real option’ in production allocation in serving the market, and the provided operational flexibility enhances their competitiveness in an uncertain environment,” Kouvelis said.

“However, persisting uncertainty together with limited reshoring capacity and cost discrepancies across production locations create ‘inertia’ in meeting market demand. As a result, global companies may continue to overflow excess demand to the offshore location.

“As a result, tariffs at any level — raw material, components and finished goods— end up increasing the cost of imported trade goods, at least in the short term,” he explained.

The authors argue it is crucial for policymakers to carefully consider the tariff level, which stage of a supply chain to execute trade restrictions on and tax credit amounts to be used.

“Very high tariffs on moderate-size markets may have unexpected effect on reshoring. Trade and industrial policies should be carefully analyzed for their effectiveness, accounting for cost disadvantages of domestic competitors and market demand strength,” the authors write.